What you won’t find in the JFK assassination file releases

|

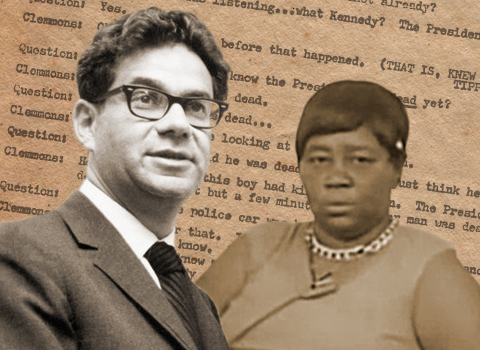

BY DALE K. MYERS

On July 19, 1964, during a New York radio interview on the Barry Gray Show, activist attorney Mark Lane dropped a bombshell – he had the tape-recorded statement of a previously unknown witness to the murder of Officer J.D. Tippit and that witness said Oswald wasn’t the killer!

You won’t find the dirty little details about this story hidden among the thousands of JFK assassination documents recently released by the National Archives – the so-called “final release” – which so far has turned out, as Archive officials have warned us for many years, to be a big yawn.

No, this story has largely been lying in plain sight among the millions of pages of documents that have been available to the public for the better part of forty-years – with one key exception: a transcript of the tape-recorded interview Mark Lane alluded to so many years ago.

The witness he described turned out to be Acquilla Clemons, a Dallas care-giver whose statements about what she saw on November 22, 1963, became the centerpiece of Lane’s efforts to exonerate Lee Harvey Oswald for the daylight murder of Officer Tippit.

However, as you’re about to find out, the real story is not what we were told.

The Barry Gray Show

Back in July, 1964, Mark Lane spoke to a radio audience in New York listening in to the Barry Gray Show:

The FBI noted that the entire transcript of the radio program shows Lane continuing “to put forth his biased, maliciously calculated, half-truths and theories in an effort to prove Oswald’s innocence.” [2]

Prima Facie

Mark Lane’s reference to Acquilla Clemons during the Barry Gray Show is a prima facie case of his willingness to sham the American public about the Tippit murder specifically and the Kennedy assassination in general.

Lane claimed that Clemons had “been questioned at our request by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Months and months ago she was questioned. She is an eyewitness to the killing of Officer Tippit. To this day she has not been called before the Warren Commission to testify…”

The “our,” above, is a reference to Lane’s “Citizens Committee of Inquiry,” a loose confederation of individuals with a singular purpose – undermine the case against Oswald in the JFK assassination.

In his 1966 book, Rush to Judgment, Lane went further, charging that the FBI conducted more than 25,000 interviews of persons having information of possible relevance to the assassination, but inexplicably failed to question Clemons. (emphasis added) [3]

In a footnote to this charge, Lane wrote that on August 21, 1964, “the FBI denied in a letter to the Commission that it knew of the existence of [Clemons] whose evidence I had discussed at public lectures,” an apparent reference to the July 19, 1964, Barry Gray Show (during which Clemons’ name was not given). This, according to Lane, constituted the FBI’s awareness of the previous unknown witness!

More importantly, there is no evidence that Lane, his associates, or any members of the Citizens Committee of Inquiry told the FBI (or any law enforcement agency for that matter) about Acquilla Clemons existence or what, if anything, she could have added to the Tippit case.

Lane himself, in his own speeches, as late as April 30, 1964, insisted that there was only one eyewitness to the Tippit shooting – namely, Helen Markham. [4]

Furthermore, there is zero evidence that the FBI interviewed Clemons “months and months” prior to Lane’s appearance on the Barry Gray Show. In fact, there is no evidence that any law enforcement agency ever interviewed Clemons.

The August 21, 1964, letter from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to Warren Commission General Counsel J. Lee Rankin, reference by Lane in Rush to Judgment says, “The files of this Bureau fail to disclose that Mr. Lane or anyone associated with him has ever furnished any information to the FBI indicating the existence of a second female eyewitness to the Tippit murder. No such individual has been identified or interviewed by this Bureau and had we knowledge of such a witness you would be promptly notified.” [5]

On October 12, 1964, two weeks after the Warren Report was released, the FBI finally learned the identity of Lane’s second female witness when The New Leader published an article by George and Patricia Nash, identifying her as Acquilla Clemmons (sic).

So, in fact, Mark Lane had not informed the FBI of Acquilla Clemons existence months before his July radio appearance, the FBI had not questioned her several times as Lane also claimed, and the Warren Commission certainly couldn’t have called her to testify considering that they didn’t know she existed. But, Mark Lane knew, and so did several of his associates.

A new witness surfaces

On June 24, 1964, Vincent J. Salandria, a high school social studies teacher and part-time lawyer; his wife Irma, and brother-in-law, Harold Feldman left Philadelphia for Dallas, intent on conducting interviews and an investigation on behalf of Mark Lane’s Citizen’s Committee of Inquiry. [6]

During the following week, they met with Marguerite Oswald, toured the Tippit murder scene and other assassination sites, attempted to interview Helen Markham, and generally canvassed the area.

It was during the last week in June that Salandria and Feldman interviewed Mrs. Clemons. It is not known how Salandria and company came to learn of Mrs. Clemons existence in the first place. Did they simply knock on doors in the neighborhood? Or were they provided a lead by Mark Lane’s Citizens Committee of Inquiry? Oddly, no record of their conversation exists, although, Salandria and Feldman did record other interviews that week. Salandria recalled in 2000, “I thought she was entirely credible.” [7]

A few days later, during the first days of July, George and Patricia Nash, a couple doing graduate work in sociology at Columbia University, who had also traveled to Dallas on behalf of Lane’s Citizens Committee of Inquiry, interviewed Helen Markham, C. Frank Wright, and Acquilla Clemons. Unlike Vincent Salandria, the Nashes were unimpressed with Clemons. [8]

According to the Nashes, Clemons claimed to have seen two men near the police car, in addition to Tippit, just before the shooting. Clemons allegedly said the FBI did question her briefly but decided not to take a statement because of her poor physical condition. She was reportedly a diabetic. The Nashes noted that Clemons’ account “was rather vague, and she may have based her story on the second-hand accounts of others at the scene,” though they thought it was probable that she was “known to some investigative agency if not to the Commission itself.” [9]

As it turns out, the Nash’s assumption that law enforcement (specifically the FBI) must have known about Clemons is demonstrably false.

The FBI had no record of Acquilla Clemons (or any similar sounding names) in their Dallas or headquarter files and “no record of a previous contact by FBI agents during the course of this investigation.” [10]

Furthermore, the FBI had no jurisdiction to investigate the Tippit murder which was strictly a local Dallas matter. The FBI only entered the case on May 13, 1964, to handle specific requests made by the Warren Commission – in particular, another Mark Lane allegation proven false: that Bernard Weissman, Jack Ruby, and J.D. Tippit had met at the Carousel Club prior to the assassination. [11]

It wasn’t until July 29, 1964, after the Warren Commission received a transcript of Lane’s remarks on the Barry Gray radio program, that the Commission asked the FBI to check into Lane’s allegation that there was a second female witness to the Tippit shooting. [12]

An October, 1964, FBI memorandum significantly notes: “Over thirteen witnesses testified before the Commission concerning the Tippit murder. The evidence developed, while circumstantial, would still make it possible for any prudent jury to return a guilty verdict against Oswald, regardless of the alleged statements of [Mr. and Mrs. C. Frank Wright] and Clemmons. (sic) The Wrights and Clemmons have yet to come forth to volunteer any information concerning this matter, and it is not felt we should interview them or inject ourselves into a strictly local murder case wherein our participation was limited to specific requests by the Commission.” [13]

As to the Dallas police investigation, the lead Tippit murder investigator, Detective James R. Leavelle, told this author practically the same thing many years ago – that he had plenty of eyewitnesses that were willing to come forward and give statements and that he didn’t need to spend valuable time searching for reluctant witnesses. Leavelle too had never heard of Acquilla Clemons until after the Nashes article came out.

Shirley Martin

In mid-July, 1964, within a few weeks of Aquilla Clemons’ contacts with Vincent Salandria and the Nashes, Oklahoma housewife-turned-sleuth Shirley Martin traveled to Dallas and interviewed Mrs. Clemons on the front porch of her place of employment, 327 E. Tenth Street – the same house in Oak Cliff where she witnessed the Tippit shooting aftermath. This time, the interview was secretly tape-recorded by Shirley’s daughter Victoria, and the tape passed on to Mark Lane. [14]

Lane later claimed that the interview was “tape-recorded in Dallas, August, 1964,” [15] although, this seems unlikely given Lane’s pronouncements on the Barry Gray radio show on July 19, 1964, in which he stated that he already had the tape-recorded Clemons interview.

You’ll recall that Lane told his radio audience on July 19 that according to that taped-interview:

In his 1966 book, Rush to Judgment, Lane wrote that “Mrs. Clemons told one independent investigator (Shirley Martin) that she had been advised by the Dallas police not to relate what she knew to the [Warren] Commission, for if she did she might be killed. The diligence of the Dallas police in this instance apparently denied to the Commission knowledge of the existence of an important witness.” [16]

This is quite laughable given the fact that Mark Lane also knew of Mrs. Clemons existence as early as mid-July, 1964, and failed to inform the Warren Commission or law enforcement authorities so that she could be properly questioned.

Still, Lane’s gift for deception goes much further. As you’ll see, none of what he told the Barry Gray radio audience is true. But who could possibly have known that?

Shirley Martin’s tape-recorded interview has been absent from the public debate for more than five decades. But now, a transcript, courtesy of assassination researcher John Kelin, has come to light. [17]

The Interview

Shirley and Vickie Martin walked up to the front porch at 327 E. Tenth Street and knocked on the door.

The Smothermans lived in the home at 327 E. Tenth in Oak Cliff. John died there in December, 1966, after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. His wife, Cornelia, died in 1985.

She don’t want me talkin’

Later in the interview, Mrs. Clemons made it crystal clear that Cornelia Smotherman didn’t want her talking to anyone about the Tippit shooting.

A policeman warns her

At the very end of the interview, Mrs. Clemons did bring up a visit paid her by a “policeman,” however it was in reference to a part of her story that had nothing to do with the Tippit shooting itself or her glimpse of the officer’s escaping killer.

According to the transcript, Mrs. Clemons told how Oswald’s mother, Marguerite, showed up with “some friends” one day to talk with her.

This could only be a reference to Saturday, June 27, 1964, when Vincent J. Salandria and Harold Feldman canvassed the Tippit shooting area with Marguerite Oswald; the three later paying a visit on Helen Markham, who live one block north.

The visit by Marguerite and her companions reminded Mrs. Clemons of something that happened on the day of the Tippit shooting.

According to Mrs. Clemons, on November 22nd, while police were clearing the crime scene, a woman who looked like Marguerite Oswald pulled up in “a fine gray car” and parked, overlooking the crime scene. The woman remained there until “everything was cleared,” and then drove away. The woman’s resemblance to Marguerite Oswald was so strong, that Mrs. Clemons mentioned the story to Marguerite when she visited on June 27th and asked her if it was in fact her in the car that day?

Marguerite answered, no, and that was the end of it. Mrs. Clemons didn’t have any idea who the woman might have been. [23]

After the interview had ended, Shirley Martin and her daughter Vickie started to walk away, only to have Mrs. Clemons call them back. Mrs. Clemons again reminded them not to tell anyone that they had talked to her.

Then, Mrs. Clemons added this:

Then, Mrs. Clemons says this:

Or could it be that Mrs. Clemons was repeating what Vincent Salandria, Harold Feldman, Marguerite Oswald, and George and Patricia Nash had told her during their visits just a few weeks earlier?

It’s worth remembering that Shirley Martin’s interview of Mrs. Clemons was conducted approximately four months after Tippit witness Warren Reynolds was shot by an unknown assailant. Rumors were rampant that Reynolds was shot because of his pursuit of Tippit’s killer, a rumor that Mark Lane was eagerly promoting in his lectures, although Dallas police believed that the two events were not connected.

Mrs. Clemons did give more details about her “police” visitor during a filmed interview with Mark Lane on March 23, 1966. Not surprisingly, most of these details were cut from the film. Here’s the exchange from an unedited transcript of the Lane interview:

Take Two:

And let’s not forget, that Mrs. Clemons initially told George and Patricia Nash a few weeks before Shirley Martin’s tape-recorded interview that the male visitor was from the FBI and that the agent only talked to her briefly but decided not to take a statement “because of her poor physical description,” she being a diabetic.

As I’ve already pointed out, the FBI denied that they had made contact with Mrs. Clemons at any time in their investigation, would not have done so given that the Tippit shooting was a local matter, and (apparently, unbeknownst to Mrs. Clemons) even if the FBI had broken protocol and contacted her, there would still be a report of that contact.

We might not be discussing the Acquilla Clemons story today had her vague and rambling version been published at the time (though to be fair, the Nashes did warn us about Mrs. Clemons’ reliability). Instead, here’s what we got, courtesy of Mark Lane and Emile de Antonio’s careful editing of their filmed interview of Clemons as it appeared in the final cut of the documentary, Rush to Judgment:

[Note that each camera CUT (designated in brackets) is an opportunity to edit the dialogue.]

What Mrs. Clemons saw

You’ll recall that according to Mark Lane, Acquilla Clemons watched Tippit drive up upon two men conversing across the street from each other. Officer Tippit stopped his car, got out, and approached one of the men who pulled a gun and shot him. The shooter then waved the other man off and the two fled in opposite directions. Lane supposedly obtained all of this from Martin’s interview of Clemons.

But, according to the transcript, that’s not what Mrs. Clemons told Shirley Martin.

According to Mrs. Clemons, she was watching news of the Kennedy assassination on television. [28] She grew tired and came out onto the front porch and sat down. [29] A tow truck was hauling a wrecked car away from the corner of Tenth and Patton. The wreck was the result of an earlier accident in which a motorist, heading south on Patton, had gone off the road, knocked over the stop sign on the southeast corner, crossed the sidewalk, plowed through the bushes, and struck the porch of the corner house at 400 E. Tenth.

This was the same house occupied by Barbara Jeanette and Virginia Davis – the eyewitnesses who saw Oswald cut across their lawn while fleeing the Tippit shooting scene. Police photographed the stop sign as part of the Tippit shooting investigation, but later determined that the two events weren’t connected.

It is not clear from the transcript whether Mrs. Clemons returned to the interior of her employer’s home or was still sitting on the front porch, however, a short time after the tow truck left with the wrecked car, the shooting of police officer unfolded.

Contrary to Mark Lane’s version of events, Mrs. Clemons did not see the shooting. She said she heard three shots.

Helen Markham was screaming and, according to Mrs. Clemons, told her to “look at the man” who had just shot the policeman. [32]

It’s doubtful that Markham even knew Clemons was there, given that she was behind Markham’s position. According to Barbara Jeannette Davis, Mrs. Markham was pointing at Oswald and screaming, “He shot him! He shot him! He killed him!” [33]

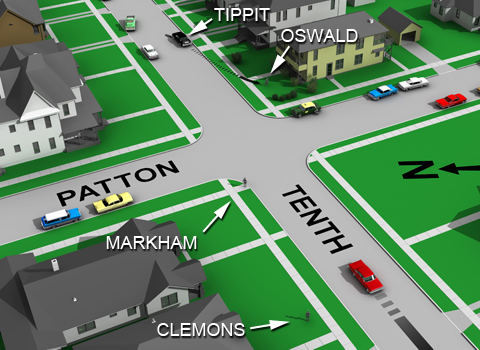

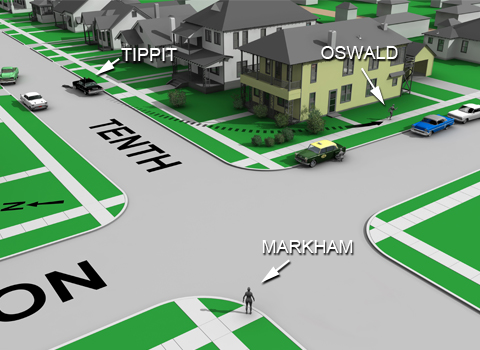

Fig. 2 | Acquilla Clemons dashes out into the front yard at 327 E. Tenth. [Graphic: DKM © 2017]

Mrs. Clemons looked diagonally across the street, toward where Mrs. Markham was pointing, and saw a man cutting across the corner lot at 400 E. Tenth as he unloaded and reloaded his gun.

Fig. 3 | Oswald escapes as Helen Markham and Acquilla Clemons look on. [Graphic: DKM © 2017]

Shirley Martin was already aware that Mrs. Clemons had told Vincent Salandria, Harold Feldman, and the Nashes that there were two men on Tenth Street at the time of the shooting. She asked Mrs. Clemons about it:

Mrs. Martin asked Acquilla Clemons what happened to the man standing across the street after the gunman ran off.

It is quite clear from the above exchange, that Mrs. Clemons didn’t think the man standing across the street from the gunman was an accomplice – as has been presented as a matter-of-fact by Mark Lane and virtually every person seeking to exonerate Oswald for the Tippit murder – but rather, that Mrs. Clemons thought the man might have been simply another eyewitness who, like her, ran away from the gunman in fear of losing his life.

In her 1966 filmed interview with Mark Lane, Mrs. Clemons reiterated what she told Shirley Martin about the two men, though you wouldn’t know that from the final cut of the film. First, here’s the unedited transcript:

[Note that each camera CUT (designated in brackets) is an opportunity to edit the dialogue.]

There is corroborating testimony for Mrs. Clemons observation that places a man across the street from Tippit’s police car shortly after the shooting.

You won’t find the dirty little details about this story hidden among the thousands of JFK assassination documents recently released by the National Archives – the so-called “final release” – which so far has turned out, as Archive officials have warned us for many years, to be a big yawn.

No, this story has largely been lying in plain sight among the millions of pages of documents that have been available to the public for the better part of forty-years – with one key exception: a transcript of the tape-recorded interview Mark Lane alluded to so many years ago.

The witness he described turned out to be Acquilla Clemons, a Dallas care-giver whose statements about what she saw on November 22, 1963, became the centerpiece of Lane’s efforts to exonerate Lee Harvey Oswald for the daylight murder of Officer Tippit.

However, as you’re about to find out, the real story is not what we were told.

The Barry Gray Show

Back in July, 1964, Mark Lane spoke to a radio audience in New York listening in to the Barry Gray Show:

LANE: We now have a statement, uh, from another witness to the, uh, Tippit killing. This is a witness who has been questioned at our request by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Months and months ago she was questioned. She is an eyewitness to the killing of Officer Tippit. To this day she has not been called before the Warren Commission to testify, and her statement is that she saw the killing of Tippit and two men were involved in the murder of Tippit, two men. One on each side of the street conversing with each other.It won’t surprise anyone familiar with Mark Lane and his penchant for twisting reality that hardly anything he had said about this newly discovered witness was true.

Tippit got out of the car and walked toward one, this man pulled out a revolver, shot that man and then both of these men, who had been conversing before the shooting, ran in opposite directions.

Thus far the Commission, which I assume must know of this testimony because we gave it to the FBI months ago and now we have given it to the Commission as well, the Commission has declined to call this eyewitness to the, this other eyewitness to the murder of Patrolman Tippit.

I have made no reference to this other eyewitness until this time. We wanted to make sure that our statements were secured from her in writing and by tape, etcetera, so there could be no question about that. We now have, uh, the statements secured in that fashion so I can’t –

BARRY GRAY: Do you –

LANE: – make reference to her.

GRAY: Do you have a statement here with you?

LANE: I am not in, uh, I do not have her permission at this time to release her statement but I hope that within the next two weeks I will be able to release her statement entirely. GRAY: To whom was her first voluntary, uh, statement made? LANE: To someone associated with our inquiry.

GRAY: No, I, I don’t mean that, Mark, I’m, I’m talking about the FBI. Did she come forward shortly after November 22nd, and say I saw the killing of Officer Tippit?

LANE: She stated this to Agents who came in that neighborhood and questioned her, yes.

GRAY: And, has, have they gone back to interview her, to interrogate her?

LANE: Yes, they have questioned her on more than one occasion.

GRAY: And she has not been called by the Commission?

LANE: She has not been called by the Commission.

GRAY: And, uh, why does she suggest this be so, or what is your suggestion?

LANE: She has no theories at all and, uh, she is, she is an excellent witness in, in the area of speculation or conjecture. She says I’m sorry I don’t know about that, and if you ask her a question, just try to lead her slightly, she said I’m sorry I just gave you all the information I have. She is very firm about what she knows and she won’t go into this area as to why they’re not calling her, she merely says I’m telling the truth and I’ll tell it to anyone who wants to hear it but I can’t tell anything I don’t know. [1]

The FBI noted that the entire transcript of the radio program shows Lane continuing “to put forth his biased, maliciously calculated, half-truths and theories in an effort to prove Oswald’s innocence.” [2]

Prima Facie

Mark Lane’s reference to Acquilla Clemons during the Barry Gray Show is a prima facie case of his willingness to sham the American public about the Tippit murder specifically and the Kennedy assassination in general.

Lane claimed that Clemons had “been questioned at our request by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Months and months ago she was questioned. She is an eyewitness to the killing of Officer Tippit. To this day she has not been called before the Warren Commission to testify…”

The “our,” above, is a reference to Lane’s “Citizens Committee of Inquiry,” a loose confederation of individuals with a singular purpose – undermine the case against Oswald in the JFK assassination.

In his 1966 book, Rush to Judgment, Lane went further, charging that the FBI conducted more than 25,000 interviews of persons having information of possible relevance to the assassination, but inexplicably failed to question Clemons. (emphasis added) [3]

In a footnote to this charge, Lane wrote that on August 21, 1964, “the FBI denied in a letter to the Commission that it knew of the existence of [Clemons] whose evidence I had discussed at public lectures,” an apparent reference to the July 19, 1964, Barry Gray Show (during which Clemons’ name was not given). This, according to Lane, constituted the FBI’s awareness of the previous unknown witness!

More importantly, there is no evidence that Lane, his associates, or any members of the Citizens Committee of Inquiry told the FBI (or any law enforcement agency for that matter) about Acquilla Clemons existence or what, if anything, she could have added to the Tippit case.

Lane himself, in his own speeches, as late as April 30, 1964, insisted that there was only one eyewitness to the Tippit shooting – namely, Helen Markham. [4]

Furthermore, there is zero evidence that the FBI interviewed Clemons “months and months” prior to Lane’s appearance on the Barry Gray Show. In fact, there is no evidence that any law enforcement agency ever interviewed Clemons.

The August 21, 1964, letter from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to Warren Commission General Counsel J. Lee Rankin, reference by Lane in Rush to Judgment says, “The files of this Bureau fail to disclose that Mr. Lane or anyone associated with him has ever furnished any information to the FBI indicating the existence of a second female eyewitness to the Tippit murder. No such individual has been identified or interviewed by this Bureau and had we knowledge of such a witness you would be promptly notified.” [5]

On October 12, 1964, two weeks after the Warren Report was released, the FBI finally learned the identity of Lane’s second female witness when The New Leader published an article by George and Patricia Nash, identifying her as Acquilla Clemmons (sic).

So, in fact, Mark Lane had not informed the FBI of Acquilla Clemons existence months before his July radio appearance, the FBI had not questioned her several times as Lane also claimed, and the Warren Commission certainly couldn’t have called her to testify considering that they didn’t know she existed. But, Mark Lane knew, and so did several of his associates.

A new witness surfaces

On June 24, 1964, Vincent J. Salandria, a high school social studies teacher and part-time lawyer; his wife Irma, and brother-in-law, Harold Feldman left Philadelphia for Dallas, intent on conducting interviews and an investigation on behalf of Mark Lane’s Citizen’s Committee of Inquiry. [6]

During the following week, they met with Marguerite Oswald, toured the Tippit murder scene and other assassination sites, attempted to interview Helen Markham, and generally canvassed the area.

It was during the last week in June that Salandria and Feldman interviewed Mrs. Clemons. It is not known how Salandria and company came to learn of Mrs. Clemons existence in the first place. Did they simply knock on doors in the neighborhood? Or were they provided a lead by Mark Lane’s Citizens Committee of Inquiry? Oddly, no record of their conversation exists, although, Salandria and Feldman did record other interviews that week. Salandria recalled in 2000, “I thought she was entirely credible.” [7]

A few days later, during the first days of July, George and Patricia Nash, a couple doing graduate work in sociology at Columbia University, who had also traveled to Dallas on behalf of Lane’s Citizens Committee of Inquiry, interviewed Helen Markham, C. Frank Wright, and Acquilla Clemons. Unlike Vincent Salandria, the Nashes were unimpressed with Clemons. [8]

According to the Nashes, Clemons claimed to have seen two men near the police car, in addition to Tippit, just before the shooting. Clemons allegedly said the FBI did question her briefly but decided not to take a statement because of her poor physical condition. She was reportedly a diabetic. The Nashes noted that Clemons’ account “was rather vague, and she may have based her story on the second-hand accounts of others at the scene,” though they thought it was probable that she was “known to some investigative agency if not to the Commission itself.” [9]

As it turns out, the Nash’s assumption that law enforcement (specifically the FBI) must have known about Clemons is demonstrably false.

The FBI had no record of Acquilla Clemons (or any similar sounding names) in their Dallas or headquarter files and “no record of a previous contact by FBI agents during the course of this investigation.” [10]

Furthermore, the FBI had no jurisdiction to investigate the Tippit murder which was strictly a local Dallas matter. The FBI only entered the case on May 13, 1964, to handle specific requests made by the Warren Commission – in particular, another Mark Lane allegation proven false: that Bernard Weissman, Jack Ruby, and J.D. Tippit had met at the Carousel Club prior to the assassination. [11]

It wasn’t until July 29, 1964, after the Warren Commission received a transcript of Lane’s remarks on the Barry Gray radio program, that the Commission asked the FBI to check into Lane’s allegation that there was a second female witness to the Tippit shooting. [12]

An October, 1964, FBI memorandum significantly notes: “Over thirteen witnesses testified before the Commission concerning the Tippit murder. The evidence developed, while circumstantial, would still make it possible for any prudent jury to return a guilty verdict against Oswald, regardless of the alleged statements of [Mr. and Mrs. C. Frank Wright] and Clemmons. (sic) The Wrights and Clemmons have yet to come forth to volunteer any information concerning this matter, and it is not felt we should interview them or inject ourselves into a strictly local murder case wherein our participation was limited to specific requests by the Commission.” [13]

As to the Dallas police investigation, the lead Tippit murder investigator, Detective James R. Leavelle, told this author practically the same thing many years ago – that he had plenty of eyewitnesses that were willing to come forward and give statements and that he didn’t need to spend valuable time searching for reluctant witnesses. Leavelle too had never heard of Acquilla Clemons until after the Nashes article came out.

Shirley Martin

In mid-July, 1964, within a few weeks of Aquilla Clemons’ contacts with Vincent Salandria and the Nashes, Oklahoma housewife-turned-sleuth Shirley Martin traveled to Dallas and interviewed Mrs. Clemons on the front porch of her place of employment, 327 E. Tenth Street – the same house in Oak Cliff where she witnessed the Tippit shooting aftermath. This time, the interview was secretly tape-recorded by Shirley’s daughter Victoria, and the tape passed on to Mark Lane. [14]

Lane later claimed that the interview was “tape-recorded in Dallas, August, 1964,” [15] although, this seems unlikely given Lane’s pronouncements on the Barry Gray radio show on July 19, 1964, in which he stated that he already had the tape-recorded Clemons interview.

You’ll recall that Lane told his radio audience on July 19 that according to that taped-interview:

- Clemons saw the killing of Tippit

- Two men were involved in the murder

- The two men stood on opposite sides of the street conversing with each other

- Tippit pulled up, got out of his car, and walked toward one man

- The man Tippit approached pulled out a revolver and shot Tippit

- Then both men, who had been conversing before the shooting, ran in opposite directions

In his 1966 book, Rush to Judgment, Lane wrote that “Mrs. Clemons told one independent investigator (Shirley Martin) that she had been advised by the Dallas police not to relate what she knew to the [Warren] Commission, for if she did she might be killed. The diligence of the Dallas police in this instance apparently denied to the Commission knowledge of the existence of an important witness.” [16]

This is quite laughable given the fact that Mark Lane also knew of Mrs. Clemons existence as early as mid-July, 1964, and failed to inform the Warren Commission or law enforcement authorities so that she could be properly questioned.

Still, Lane’s gift for deception goes much further. As you’ll see, none of what he told the Barry Gray radio audience is true. But who could possibly have known that?

Shirley Martin’s tape-recorded interview has been absent from the public debate for more than five decades. But now, a transcript, courtesy of assassination researcher John Kelin, has come to light. [17]

The Interview

Shirley and Vickie Martin walked up to the front porch at 327 E. Tenth Street and knocked on the door.

MARTIN: Hello. Are you Mrs. Clemons?Now, any journalism 101 student would know that the next question would be, “Who told you not to talk to anyone?” But, Mrs. Clemons isn’t being interviewed by a schooled journalist. She’s being interviewed by a housewife from Oklahoma who has already expressed a bias toward Oswald’s total innocence. Not surprisingly, Mrs. Martin asks a leading question:

CLEMONS: Yes.

MARTIN: You are? May I speak to you a moment? … We’d like to talk to you about what you saw on Friday, November 22.

CLEMONS: I (can’t). It’s been too long. Mrs. Clemons immediately pleads that it’s been too long (over seven months has passed since the shooting) and that she can’t recall details.

MARTIN: Well, has anyone talked to you and told you not to talk to anyone?

CLEMONS: Yes, they have.

MARTIN: Is that the Dallas police?Mrs. Martin is in fact a private citizen, but she’s not in Dallas simply to satisfy her own curiosity, she’s there on behalf of Mark Lane’s Citizens Committee of Inquiry (and will turn the secretly tape-recorded interview over to him at the earliest opportunity), and her daughter’s children’s book is an admitted ruse. [18]

CLEMONS: Some of them.

MARTIN: Well, I’m just a private citizen. I’m not representing any group. My daughter is trying to write a children’s book.

CLEMONS: They don’t allow me to say anything. I’m not allowed to say anything.The persons referred to as “they” is not explained – yet. Mrs. Martin digs deeper, looking for the sinister forces she believes are behind Oswald’s frameup.

MARTIN: Who’s that? You mean the Dallas police?Somebody??? Mrs. Martin is practically handing Mrs. Clemons a villain – any villain – yet she bats each suggestion away like a foul-ball hitter. Finally, what I believe is the real truth tumbles out.

CLEMONS: Some of them. I don’t know. I don’t know one of them from the other.

MARTIN: From the Government?

CLEMONS: I guess it was. I don’t know who.

MARTIN: From Washington?

CLEMONS: Somebody. [19]

CLEMONS: But see, I take care of an ill man here. And she don’t want me in anything because it would upset him. She’s awful fond of me… [20]This is the first ah-hah moment – one that has been hidden from public scrutiny for better than fifty years Here, for the first time, we have Mrs. Clemons explaining that it’s not a cadre of faceless, nameless law enforcement officers harassing her to keep quiet (as everyone has been led to believe by Mark Lane and the conspirati), but rather, a strong suggestion by her employers – John and Cornelia Smotherman – who are no doubt sick and tired of the parade of “journalists” (remember, this is the third visit in as many weeks) who keep showing up at her home.

The Smothermans lived in the home at 327 E. Tenth in Oak Cliff. John died there in December, 1966, after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. His wife, Cornelia, died in 1985.

She don’t want me talkin’

Later in the interview, Mrs. Clemons made it crystal clear that Cornelia Smotherman didn’t want her talking to anyone about the Tippit shooting.

MARTIN: And no one… someone has come to you since those people came and told you not to give anything to the newspapers… well, I’m not with the newspapers.And later still, the fact that Cornelia Smotherman didn’t want Mrs. Clemons talking to anyone came up again:

CLEMONS: I’m just not allowed to tell you. I can’t tell you nothing. I don’t know nothing.

MARTIN: And have you been to the Warren Commission? In Washington?

CLEMONS: No, ma’am.

MARTIN: No? Did they come and take a statement from you or anything?

CLEMONS: No. I wouldn’t give none, ‘cause I’m not allowed to tell nothing. Lady I work for, she don’t want me…

MARTIN: Involved?

CLEMONS: No, she don’t. I can’t be involved ‘cause she’s not well either. [21]

CLEMONS: Well, I just wouldn’t want you to mention anything I’ve said. The lady I work for here… things would go hard for me with her… what I mean, I don’t want you to mention talking to me because I would get into trouble… I’m not allowed to talk to anybody but I just wanted to tell you that don’t be mentioning me because this lady here, I’d probably lose my job. [22]So, again – the cops aren’t pressuring Mrs. Clemons to keep quiet. Her employers, John and Cornelia Smotherman, are the ones telling her to keep still. The real question is: Why has this exchange been literally excised from every account of the Acquilla Clemons story to date?

A policeman warns her

At the very end of the interview, Mrs. Clemons did bring up a visit paid her by a “policeman,” however it was in reference to a part of her story that had nothing to do with the Tippit shooting itself or her glimpse of the officer’s escaping killer.

According to the transcript, Mrs. Clemons told how Oswald’s mother, Marguerite, showed up with “some friends” one day to talk with her.

This could only be a reference to Saturday, June 27, 1964, when Vincent J. Salandria and Harold Feldman canvassed the Tippit shooting area with Marguerite Oswald; the three later paying a visit on Helen Markham, who live one block north.

The visit by Marguerite and her companions reminded Mrs. Clemons of something that happened on the day of the Tippit shooting.

According to Mrs. Clemons, on November 22nd, while police were clearing the crime scene, a woman who looked like Marguerite Oswald pulled up in “a fine gray car” and parked, overlooking the crime scene. The woman remained there until “everything was cleared,” and then drove away. The woman’s resemblance to Marguerite Oswald was so strong, that Mrs. Clemons mentioned the story to Marguerite when she visited on June 27th and asked her if it was in fact her in the car that day?

Marguerite answered, no, and that was the end of it. Mrs. Clemons didn’t have any idea who the woman might have been. [23]

After the interview had ended, Shirley Martin and her daughter Vickie started to walk away, only to have Mrs. Clemons call them back. Mrs. Clemons again reminded them not to tell anyone that they had talked to her.

CLEMONS: Because, I’m not allowed to tell anyone that I even seen her.The “her” in Mrs. Clemons response is a reference to either the woman who looked like Marguerite Oswald that drove up the day of the shooting, or perhaps, the visit paid by the real Marguerite Oswald herself on June 27, 1964. Shirley Martin didn’t ask any follow up question to clarify the reference. [24]

Then, Mrs. Clemons added this:

CLEMONS: Because, you know, some kind of policeman talked to me. You know I don’t know one from another.Mrs. Clemons never responds to the question of whether she was shown a badge, but clearly the man referred to by Mrs. Clemons as “some kind of a policeman” was not a uniformed officer.

MARTIN: Was it a plainclothesman?

CLEMONS: No, he wasn’t plainclothes.

MARTIN: He had a police officer’s uniform?

CLEMONS: Had blue-looking clothes on.

MARTIN: Cap?

CLEMONS: Yes.

MARTIN: Had a star… badge?

CLEMONS: And I’m not supposed to be talking to anybody, because he said if I talked to anybody I might have to go to Washington… be gone so long…be taking pictures of me. [Mrs. Smotherman] just don’t want that.Again, Mrs. Clemons is worried about being called away from her job to testify and the additional publicity that testifying would bring – both of which could jeopardize her job with the Smothermans.

MARTIN: Oh, I see. So, the police said you’d get a lot of publicity and you’d better not do it?

CLEMONS: Yeah, I’d better not.

Then, Mrs. Clemons says this:

CLEMONS: Might get killed on the way to work. See I live over there.Mrs. Clemons didn’t clarify who “they” are that told her to “be careful” and Shirley Martin didn’t ask. It seems a strange remark if in fact Mrs. Clemons was referring to the “policeman” who she described as a single individual who paid her one visit.

MARTIN: Is that what the policeman said?

CLEMONS: Yes. See they’ll kill people that know something about that. There’s liable to be a whole lot of them.

MARTIN: Who?

CLEMONS: There might be a whole lot of Oswalds and things. You know, you don’t know who you talk to, you just don’t know.

MARTIN: You scare me…

CLEMONS: You have to be careful. You get killed.

MARTIN: That’s what the police said too?

CLEMONS: Sure. They told me that I had to be careful. [25]

Or could it be that Mrs. Clemons was repeating what Vincent Salandria, Harold Feldman, Marguerite Oswald, and George and Patricia Nash had told her during their visits just a few weeks earlier?

It’s worth remembering that Shirley Martin’s interview of Mrs. Clemons was conducted approximately four months after Tippit witness Warren Reynolds was shot by an unknown assailant. Rumors were rampant that Reynolds was shot because of his pursuit of Tippit’s killer, a rumor that Mark Lane was eagerly promoting in his lectures, although Dallas police believed that the two events were not connected.

Mrs. Clemons did give more details about her “police” visitor during a filmed interview with Mark Lane on March 23, 1966. Not surprisingly, most of these details were cut from the film. Here’s the exchange from an unedited transcript of the Lane interview:

LANE: Did anyone come and see you after the murder of Officer Tippit?Uh-oh! Mrs. Clemons’ answers didn’t quite fit the narrative that Mark Lane was attempting to build – one in which the Dallas police were threatening her to keep quiet about what she saw on Tenth Street, a charge Lane had already made – so he tried again.

CLEMONS: Yes, there was a man came with some cameras and talked to me and I wouldn’t talk to him and [he] left away. (emphasis added) Mrs. Clemons’ response wasn’t what Lane was hoping for, so he tried again.

LANE: Yes. Did a police officer come to visit you after Officer Tippit was killed?

CLEMONS: I don’t know what he was. He came to my house and talked to me, but I don’t know what he – looked like a policeman to me.

LANE: He did? Did he have a gun?

CLEMONS: Yes, he wore a gun.

LANE: And did he say anything to you?

CLEMONS: He just told me, uh, it’d be the best if I didn’t say anything because I might get hurt.

LANE: It’d be best if you didn’t say anything about –

CLEMONS: Uh-huh… I haven’t said anything –

LANE: Did he tell you it would be best if you didn’t say anything about seeing Officer Tippit killed or see the man with the gun?

CLEMONS: No, no – he just said it would be best if I didn’t say I seen anything.

LANE: I see. And, did he say he was from the Police Department?

CLEMONS: He didn’t say; I didn’t ask him.

Take Two:

LANE: Did a man come and talk with you?So, to recap in a slightly more coherent manner, Mrs. Clemons tells Shirley Martin and Mark Lane that about two days after the Tippit shooting – Sunday or Monday, November 24-25, 1963 – a man wearing blue-looking clothes (but not a uniform), carrying cameras and wearing a gun, came to her home (she never explains how the man knew where she lived) and without identifying himself (she assumes he’s a policeman) asks to speak to her. She refuses to talk to him and he leaves, but not before he tells her that it would be best if she didn’t say anything because she might get hurt.

CLEMONS: A man came to talk with me and told me it would be best for me to don’t talk. And I didn’t say anything to him that I would or – what I wouldn’t –

LANE: Did he tell you what might happen if you did talk?

CLEMONS: ‘Said that I might get hurt – or someone might hurt me if I would talk.

LANE: About what you saw?

CLEMONS: - what I saw.

LANE: Mrs. Clemons, how long after Tippit was shot did this man with the gun come to visit you?

CLEMONS: Uh – ‘bout two days. It was about two days. [26]

And let’s not forget, that Mrs. Clemons initially told George and Patricia Nash a few weeks before Shirley Martin’s tape-recorded interview that the male visitor was from the FBI and that the agent only talked to her briefly but decided not to take a statement “because of her poor physical description,” she being a diabetic.

As I’ve already pointed out, the FBI denied that they had made contact with Mrs. Clemons at any time in their investigation, would not have done so given that the Tippit shooting was a local matter, and (apparently, unbeknownst to Mrs. Clemons) even if the FBI had broken protocol and contacted her, there would still be a report of that contact.

We might not be discussing the Acquilla Clemons story today had her vague and rambling version been published at the time (though to be fair, the Nashes did warn us about Mrs. Clemons’ reliability). Instead, here’s what we got, courtesy of Mark Lane and Emile de Antonio’s careful editing of their filmed interview of Clemons as it appeared in the final cut of the documentary, Rush to Judgment:

[Note that each camera CUT (designated in brackets) is an opportunity to edit the dialogue.]

LANE: Did anyone come to see you after the murder of Officer Tippit?Regardless of Lane’s creative editing, it’s difficult to imagine that any law enforcement officer would have warned or threatened Mrs. Clemons with injury or death because of what she had seen – especially given the fact that she hadn’t really seen anything of consequence.

CLEMONS: Yes, he was a man, came, [CUT-A-WAY to LANE] I don’t know what he was. He came to my house [CUT to close-up of CLEMONS] and talked to me, but I don’t know what he – looked like a policeman to me.

LANE: He did? Did he have a gun?

CLEMONS: Yes, he wore a gun.

[CUT to LANE, pan right to CLEMONS]

LANE: Mrs. Clemons, how long after Tippit was shot did this man with a gun come to visit you?

CLEMONS: About two – about two days. [CUT to LANE] It was about two days, said that I might get hurt, [CUT to medium shot of CLEMONS] someone might hurt me, if I would talk.

LANE: About what you saw?

CLEMONS: What I saw. [CUT to close-up of CLEMONS] He just told me to, be best if I didn’t say [“Mrs. Acquilla Clemons” TEXT REMOVED] anything because I might get hurt. [27]

What Mrs. Clemons saw

You’ll recall that according to Mark Lane, Acquilla Clemons watched Tippit drive up upon two men conversing across the street from each other. Officer Tippit stopped his car, got out, and approached one of the men who pulled a gun and shot him. The shooter then waved the other man off and the two fled in opposite directions. Lane supposedly obtained all of this from Martin’s interview of Clemons.

But, according to the transcript, that’s not what Mrs. Clemons told Shirley Martin.

According to Mrs. Clemons, she was watching news of the Kennedy assassination on television. [28] She grew tired and came out onto the front porch and sat down. [29] A tow truck was hauling a wrecked car away from the corner of Tenth and Patton. The wreck was the result of an earlier accident in which a motorist, heading south on Patton, had gone off the road, knocked over the stop sign on the southeast corner, crossed the sidewalk, plowed through the bushes, and struck the porch of the corner house at 400 E. Tenth.

This was the same house occupied by Barbara Jeanette and Virginia Davis – the eyewitnesses who saw Oswald cut across their lawn while fleeing the Tippit shooting scene. Police photographed the stop sign as part of the Tippit shooting investigation, but later determined that the two events weren’t connected.

It is not clear from the transcript whether Mrs. Clemons returned to the interior of her employer’s home or was still sitting on the front porch, however, a short time after the tow truck left with the wrecked car, the shooting of police officer unfolded.

Contrary to Mark Lane’s version of events, Mrs. Clemons did not see the shooting. She said she heard three shots.

CLEMONS: I thought it was firecrackers. I wasn’t paying any attention. [30]Mrs. Clemons ran out onto the front lawn of the Smotherman residence, located two houses west of Tenth and Patton on the north side of the Tenth street. She stopped near the sidewalk and looked eastward toward the Patton. [31]

Helen Markham was screaming and, according to Mrs. Clemons, told her to “look at the man” who had just shot the policeman. [32]

It’s doubtful that Markham even knew Clemons was there, given that she was behind Markham’s position. According to Barbara Jeannette Davis, Mrs. Markham was pointing at Oswald and screaming, “He shot him! He shot him! He killed him!” [33]

|

Mrs. Clemons looked diagonally across the street, toward where Mrs. Markham was pointing, and saw a man cutting across the corner lot at 400 E. Tenth as he unloaded and reloaded his gun.

CLEMONS: He went across that lot there, that’s all I know. He went across that lot, I don’t know which way… I don’t know which way he went after I seen him unloading and loading his gun. That’s all I seen…. [34] I was afraid. He frightened me. To come out and see him unloading his gun and reload it. But, I didn’t pay no attention [to what he was wearing]. I just tried to get out of the way, because I thought he was going to shoot me… and I didn’t pay him any mind. I was getting out of the way… [35] See, I was pretty close to him. [He was] between that telegram (sic) post and that tree, loading his gun... And I was on this side of the walk standing right there and I didn’t want him to be shooting me. [36]

|

Shirley Martin was already aware that Mrs. Clemons had told Vincent Salandria, Harold Feldman, and the Nashes that there were two men on Tenth Street at the time of the shooting. She asked Mrs. Clemons about it:

MARTIN: There were supposed to be two men weren’t there?Later in the interview, Martin asked Mrs. Clemons if she heard the two men “yell or say anything” to each other.

CLEMONS: Well, it was two men. I don’t know, I wouldn’t know them if I was to see them.

MARTIN: No, of course not. I wouldn’t expect you to do that. They were both on that same corner?

CLEMONS: I don’t know. All I know, he was talking to [unintelligible] who done the shooting [unintelligible]. [The gunman] was talking to a tall guy on the other side of the street with yellow khakis and a white shirt on, but I don’t know whether he was in it or he was just going to get out of the way or something. I don’t know because I had to go back in and tend to [Mr. Smotherman]. [37]

CLEMONS: No. I heard no more than I heard that lady call. She told me to look at the man shooting the police. [38]This seems to contradict Mrs. Clemons’ earlier comment that “He (the gunman) was talking to a tall guy on the other side of the street” [39] As will be seen in a moment, Mrs. Clemons apparently surmised the supposed conversation from gestures the gunman made.

Mrs. Martin asked Acquilla Clemons what happened to the man standing across the street after the gunman ran off.

MARTIN: The other one went up that… Patton?Here, too, is another ah-hah moment – a sharp, left-turn off the path that we were led down fifty-three years ago.

CLEMONS: Yeah. He went up [unintelligible]. He may have been just a boy getting out of the way. [emphasis added]

MARTIN: Scared maybe.

CLEMONS: Yeah. Probably somebody he told to get out of his way or something… [40]

It is quite clear from the above exchange, that Mrs. Clemons didn’t think the man standing across the street from the gunman was an accomplice – as has been presented as a matter-of-fact by Mark Lane and virtually every person seeking to exonerate Oswald for the Tippit murder – but rather, that Mrs. Clemons thought the man might have been simply another eyewitness who, like her, ran away from the gunman in fear of losing his life.

In her 1966 filmed interview with Mark Lane, Mrs. Clemons reiterated what she told Shirley Martin about the two men, though you wouldn’t know that from the final cut of the film. First, here’s the unedited transcript:

LANE: And was there any other man there?Mrs. Clemons’ reply doesn’t make much sense as transcribed. It seems more likely, especially given what she told Shirley Martin, that what she meant to say is that “I don’t know whether he (the man across the street) was with him (the gunman), or not.” In any event, her reply didn’t fit the story Lane wanted to tell. He tried again.

CLEMONS: Yes, there was one on the other side of the street, but I don’t know what is with him, or not. All I know, he told him to go on.

LANE: Now, you saw this man on the other side of the street –Again, Mrs. Clemons tells Lane the same thing she told Shirley Martin – she couldn’t tell if the two men shared words. Lane tried again:

CLEMONS: Uh-huh.

LANE: And did the man with the gun talk to the man on the other side of the street. (emphasis in original)

CLEMONS: I couldn’t tell.

LANE: Did he motion to him?Once again, according to Mrs. Clemons, there is no exchange of dialogue between the two men – just brief eye contact, and then they run in opposite directions. Lane tries again to paint a picture of two accomplices on Tenth Street:

CLEMONS: He just looked at him and went on.

LANE: Mrs. Clemons – er – the man who had the gun – uh – did he make any motion at all to the other man across the street?Actually, Mrs. Clemons had just said that she couldn’t tell if words were exchanged. No matter, Lane simply put the words he wanted to hear into Mrs. Clemons’ mouth and she then dutifully repeated them:

CLEMONS: No more’n told him to go on.

LANE: Well, he waved his hand and said, “Go on.”

CLEMONS: Yes, said, “Go on.”After some careful editing, Lane had his accomplice. Here’s Acquilla Clemons’ statement about the two men as it appears in the final cut of the film, Rush to Judgment:

LANE: And then what happened with the man with the gun?

CLEMONS: Er – he unloaded and reloaded.

LANE: And what did the other man do?

CLEMONS: Man kept going – straight down the street.

LANE: And then did they go in opposite directions?

CLEMONS: Yes, they were – they weren’t together, they went this way from each other – the one done the shooting went this way; other went straight down Tenth Street that way. [41]

[Note that each camera CUT (designated in brackets) is an opportunity to edit the dialogue.]

LANE: And was there any other man there?Once again, Mark Lane manipulates the Acquilla Clemons story – turning what Clemons herself thought was probably another eyewitness running for his life, into an accomplice in the Tippit shooting.

CLEMONS: Yes, there was one on the other side of the street. [DISSOLVE CUT] All I know is he told him to go on.

[CUT to medium shot of CLEMONS.]

LANE: Mrs. Clemons, the man who had the gun, did he make any motion at all to the other man across the street?

CLEMONS: No more - told him to go on. [indicating with a dismissive gesture using her right arm]

LANE: Oh, he waved his hand and said, “Go on?”

CLEMONS: Yeah, said, “Go on.” [indicating again with a dismissive gesture using her right arm]

LANE: And then what happened with the man with the gun?

CLEMONS: He unloaded it and reloaded it.

LANE: And what did the other man do?

CLEMONS: The man kept going, straight down the street.

LANE: And then did they go in opposite directions?

CLEMONS: Yes, they were – they – they weren’t together, they went this way from each other. [indicating with arms moving wide apart] The one done the shooting went this way [indicating with her right arm that the gunman was moving directly away from her, south on Patton], the other one went straight down Tenth Street, that way [indicating with her left arm that the second man was moving away from her to her left, east along the north side of Tenth Street]. [42]

There is corroborating testimony for Mrs. Clemons observation that places a man across the street from Tippit’s police car shortly after the shooting.

|

As I wrote in my book, With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit:

Frank Cimino lived in an apartment at 405 East Tenth Street, directly across the street from Tippit’s squad car. He told the FBI that he was in his apartment listening to the radio when he heard “four loud noises which sounded like shots, and then he heard a woman scream.”The shooting aftermath

Cimino jumped up, slipped on his shoes, and ran outside the house where he encountered a hysterical Helen Markham. She shouted at Cimino, “Call the police!” The waitress explained that a man had just shot a police officer and pointed in the direction of the alley between Tenth and Jefferson, off Patton. Cimino looked but could not see anyone. He walked over toward Tippit and saw that he had been shot in the head. Just then, people came running from all directions.

Cimino’s account matches the time period which Acquilla Clemons claimed that a man was standing across the street from Tippit’s squad car. Was Mrs. Clemons’ “accomplice” really Cimino? It seems likely, considering the timing of Frank Cimino’s actions and Clemons’ distance from the scene. [43]

We know from a multitude of cross-matching testimony, that as the two men ran off, Mrs. Helen Markham ran toward Officer Tippit’s body. What isn’t widely known is that Acquilla Clemons followed her.

CLEMONS: … [Mrs. Markham] runned in front of me and I went down there when – when I went down there, there wasn’t anybody there but her. I guess she was there. I don’t know. It was all excitement… (emphasis in original) [44]At one point, Mrs. Martin asked:

MARTIN: And you think the policeman died right away?Mrs. Martin asked Acquilla if she remembered which way Tippit’s car was facing – east or west?

CLEMONS: He did. He died before I got there. [45]

CLEMONS: I can’t remember that. I don’t know. I went down there and looked at him (Tippit), but I don’t know. I forgot – it was just an upset day. I couldn’t think. I don’t know which way the car was. I been trying to think. [46]Mrs. Clemons told Shirley Martin that “a lot of people came running out” and that “someone” (we now know to be Domingo Benavides) tried to notify police of the shooting using Tippit’s car radio:

CLEMONS: All I know, somebody got up in that car to call the police. I went to the door to call the police and I couldn’t get in. I had left him – and I don’t know who, I don’t know how they got them. Somebody called them on the police car. I don’t know who it was ‘cause I had to come back here. [Mr. Smotherman] was very sick. I didn’t pay anything – any attention ‘cause I was just looking. ‘Cause [Mr. Smotherman] was awful sick and I had to go. [47]Although it is not entirely clear, Mrs. Clemons seems to be saying that she witnessed Domingo Benavides’ unsuccessful attempts to use Tippit’s radio, before she returned to the Smotherman house (she uses the word “door,” instead of “house”) and tried to call police herself from there, but couldn’t get through. [48]

Within a few minutes, Mrs. Clemons told Martin, there were “so many policemen you couldn’t walk out there.” [49]

Oddly, Mrs. Clemons insisted that Tippit was shot “early in the morning.” Pressed as to the exact time, Mrs. Clemons explained that she usually ate lunch at 11:30 a.m., and that the shooting occurred before then. [50] It’s clear from the transcript that not even Shirley Martin believed Mrs. Clemons’ timing of the shooting.

Of course, there is ample evidence to show Tippit was killed at about 1:15 p.m., but don’t be surprised to see future bottom-feeders citing Acquilla Clemons’ statements as supporting evidence for a shooting time – any shooting time – that will exonerate Oswald from culpability.

A short stocky man

Finally, in his 1966 book, Rush to Judgment, and the film of the same title, Mark Lane made a big deal out of Acquilla Clemons’ description of the killer:

On March 23, 1966, I interviewed Mrs. Clemons at her home at 618 Corinth Street Road in Dallas. During our filmed and tape-recorded conversation, she described the gunman as ‘kind of a short guy’ and ‘kind of heavy’ and said that the other man was tall and thin and wore light khaki trousers and a white shirt. [51]Two years earlier, during a secretly tape-recorded interview, Lane had badgered Helen Markham into describing the gunman as “a short man, somewhat on the heavy side, with slightly bushy hair.” He was all too happy to allow audiences to note the similarities between the two women’s description of the shooter – and in particular – that the description didn’t fit Oswald.

However, Mrs. Clemons makes it crystal clear to Shirley Martin that she didn’t pay any attention to the shooters’ clothing or description. Asked whether the man across the street was wearing a coat or a jacket, Mrs. Clemons said:

CLEMONS: No. The other man (gunman) had on a jacket, but [unintelligible] it’s been so long. I don’t know.Later in the interview, Shirley Martin returns to the subject:

MARTIN: But it was white? (emphasis in original)

CLEMONS: One (the man across the street) had a white. I don’t know what the other one (gunman) had. But I didn’t pay no attention. I just tried to get out of the way because I thought he was going to shoot me – and I didn’t pay him any mind. I was getting out of the way.

MARTIN: And the one with the gun had the white shirt on?

CLEMONS: No, the one with the khakis had the white shirt on – was on the other side of the street. I don’t know what the one with the gun had on because I was getting out of the way. [52]

MARTIN: And this man [with the gun] who ran this way, his top color was what?Shirley’s daughter, Vickie, who prepared the transcript notes: “Here she had begun to say ‘brown.’” Oswald, of course, was wearing a brown shirt when arrested at the Texas Theater. Mrs. Clemons continued:

CLEMONS: I can’t remember. I was afraid. He frightened me. To come out and see him unloading his gun and reload it.

MARTIN: He didn’t have a white shirt on?

CLEMONS: I didn’t [unintelligible]. He may have had some bro – I don’t know.

CLEMONS: The other one had on white – with the gun – I didn’t pay him much attention ‘cause I was getting out of his way. He acted like he wanted to shoot me.Out of the blue, Shirley Martin asks a leading question:

MARTIN: Was he a short, kind of heavy-set man?Despite Mrs. Clemons repeated statements that she didn’t pay any attention to what the gunman was wearing or what he looked like, Shirley Martin managed to elicit from Clemons a description anyway – one that fit Martin’s own narrative of an innocent Oswald.

CLEMONS: Yes, he was short. Heavy.

MARTIN: He was kind of heavy?

CLEMONS: Yeah, he was kind of stocky-built. Stocky-build – whatever you call it.

MARTIN: You wouldn’t say he was kind of thin?

CLEMONS: No, I wouldn’t, ‘course he was just awful [fat or fast (the transcriber isn't sure which she said)]. I just saw him and I was getting out of his way.

MARTIN: And did you notice his hair as all? Was it thick hair?

CLEMONS: No. I didn’t pay his hair any attention. I was getting out of his way… [53]

Unfortunately, Mrs. Clemons description of a “stocky” gunman would have had more bite if Shirley Martin had allowed Clemons to describe the gunman on her own. But, apparently, Mrs. Martin couldn’t risk that, or resist the temptation to insert her own views into the historic narrative.

If you strip away all the malarkey and manipulation that’s been added to the Acquilla Clemons story, one single cohesive picture begins to emerge. The minor details that she brings to the table about the murder on Tenth Street only support that which we already know to be true based on physical evidence and the testimony of a myriad of other witnesses – and that truth is that Lee Harvey Oswald murdered J. D. Tippit.

The dirty details

When it comes to the malicious distortion of the truth for personal and ideological gain, few in the history of the assassination story have managed to crawl as low as Mark Lane.

Heralded by a generation unwilling to confront his deceptions, dishonesty, and repeated cover-ups, Lane’s handling of the Acquilla Clemons story should serve as the primary exhibit of what lengths dedicated propogandists are willing to go to twist the simple, uncomplicated truth into a pack of fables that serve their own deceitful ends.

As with most lies, the truth can be found in the dirty little details. [END]

[Read: With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit (Oak Cliff Press, 2013) by Dale K. Myers – the only definitive second-by-second account of the life and death of the forgotten Dallas patrolman.]

Endnotes

[1] FBI 105-82555, Oswald HQ File, Section 201 [aka FOIPA#233,988] / FBI Letterhead Memo, Aug. 11, 1964, Barry Gray Show Transcript, July 19, 1964, pp.9-10

[2] FBI 105-82555, Oswald HQ File, Section 201 / FBI Airtel, SAC Dallas to Director, August 13, 1964, p.2

[3] Lane, Mark, Rush to Judgment, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1966, p.176

[4] Warren Commission, Mark Lane, Key Persons File, CD1418a, FBI Letterhead Memorandum, August 7, 1964, p.2

[5] FBI 62-109090, Warren Commission HQ File, Section 18, p.99 / FBI Letter, Director to J. Lee Rankin, August 21, 1964, p.1

[6] Kelin, John, Praise from a Future Generation, Wings Press, San Antonio, TX, 2007, p.62

[7] “credible,” Ibid, p.93, Fn 38 [Note: In a letter dated June 23, 1964, Deirdre Griswold, secretary of the Citizens Committee of Inquiry (CCI), sent Vincent Salandria six pages of “important leads” including questions, copies of affidavits, and other information to get Salandria started on his forthcoming Dallas investigation. A card file that the CCI maintained “included names that, Griswold said, had only rarely appeared in the public record.” (Kelin, John, Praise from a Future Generation, Wings Press, San Antonio, TX, 2007, p.62)]

[8] Kelin, op.cit., pp.91, 94; Nash, George and Patricia, “The Other Witnesses,” The New Leader, October 12, 1964, FBI 62-109090 Warren Commission HQ File, Section 24, pp.139-143

[9] Nash, op. cit.

[10] FOIPA No.233,988 – Acquilla Clemmons, 1984; / FBI Airtel, SAC Dallas to Director, Oct 21, 1964, pp.1-4; aka FBI 105-82555 Oswald HQ File, Section 218, pp.66-69

[11] FBI 124-10369-10019, pp.236-237 / FBI Airtel, Director to SAC Dallas, May 13, 1964, pp.1-2

[12] FBI 62-109090, Warren Commission HQ File, Section 18, p.99 / FBI Letter, Director to J. Lee Rankin, August 21, 1964, p.2

[13] FOIPA No.233,988 – Acquilla Clemons, 1984; / FBI Memorandum, Belmont to Rosen, Oct 28, 1964, p.2; aka FBI 62-109090 Warren Commission HQ File, Section 24, p.138

[14] Kelin, John, Praise from a Future Generation, Wings Press, San Antonio, TX, 2007, p.94

[15] Lane, op. cit., p.190. Fn 8

[16] Ibid, p.194

[17] Note: Kelin obtained the transcript from Shirley Martin and published only selected portions of it in his 2007 book, Praise from a Future Generation (pp.94-98).

[18] Kelin, op. cit.

[19] Taped conversation with Mrs. Acquilla Clemons, interviewed by Shirley Martin, mid-July, 1964, p.1

[20] Ibid, p.1

[21] Ibid, p.6

[22] Ibid, p.7

[23] Ibid, p.5

[24] Note: In the transcript, Vickie Martin typed: “Her who?” next to this reference.

[25] Ibid, pp.7-8

[26] Emile de Antonio Papers at Wisconsin Center for Film & Theater Research, Wisconsin Historical Society, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Box 60, Folder 1, pp.30-32; Transcript of filmed interview of Acquilla Clemons, pp.4-6

[27] Excerpt from the film, Rush to Judgment (1966)

[28] Clemons, 1964, op.cit, p.3

[29] Ibid, p.6

[30] Ibid, p.5

[31] Ibid, p.4

[32] Ibid, p.4

[33] CD87, p.556, Secret Service affidavit of Barbara Jeanette Davis, Dec. 1, 1963; 3H343-344, WCT of Barbara Jeanette Davis, March 26, 1964

[34] Clemons, 1964, op. cit., p.3

[35] Ibid, p.2

[36] Ibid, p.4

[37] Ibid, p.2

[38] Ibid, p.4

[39] Note: The transcript, prepared by Vickie Martin, contains a notation to this effect: “Earlier, however, she says they were talking together.”

[40] Ibid, p.3

[41] Emile de Antonio Papers at Wisconsin Center for Film & Theater Research, Wisconsin Historical Society, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Box 60, Folder 1, pp.28-29; Transcript of filmed interview of Acquilla Clemons, pp.2-3 [Note: The unedited transcripts reads “…other went straight down past street that way,” however, in the final cut of the film, Mrs. Clemons can clearly be heard to say “down Tenth Street that way.”]

[42] Excerpt from the film, Rush to Judgment (1966)

[43] Myers, Dale K., With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, (Oak Cliff Press, 2013, p.124; CD7, p.411, FBI Interview of Frank Cimino, Dec. 4, 1963

[44] Ibid, p.4

[45] Ibid, p.5

[46] Ibid, p.3

[47] Ibid, p.3

[48] Note: Upon a first reading, I thought that Mrs. Clemons might have attempted to use the police radio to call police, however, there is no corroborating testimony to support that notion, no reason to suppose that Mrs. Clemons would have been bold enough to make such an attempt, and more importantly, very clear that she was worried about being away from her patient, Mr. Smotherman, and did in fact return to the Smotherman home at about this time. It seems more likely, therefore, that she made an attempt to call police from the house, and simply misspoke during the taped interview.

[49] Ibid, p.4

[50] Ibid, p.6

[51] Lane, op. cit., p.194

[52] Clemons, 1964, op. cit., p.2

[53] Ibid, p.4

9 comments:

Dale, correct me if I’m wrong. Tippit’s car was in front of 411 Tenth Street. The Smothermans lived on 327 Tenth. You have the Smothermans living “opposite” the street when they should be on the same side of the street (odd numbers).

You're wrong. Tippit was parked in front of 404 E. Tenth, the opposite side of the street as the Smotherman home at 327 E. Tenth.

Dale,

another excellent piece. Very many thanks for researching and posting it. It's extensive, detailed, authoritative and - above all - damning of Mark Lane.

The man was without scruple. He was berated by the Warren Commission and the HSCA yet remained impervious to the fact that he'd been exposed as a charlatan. He just spent his entire life lying to the public.

I was pleased to see that in your essay you noted that Clemons DID NOT SEE the Tippit killing. There are many who seem to believe that she did. Even in Lane's film she makes no claim to have seen the murder; she just speaks of hearing the shots, as you point out.

The above piece is an excellent expose of one of the most duplicitous men ever to hitch a ride on the assassination bandwagon.

I fully agree with your summary that,

"When it comes to the malicious distortion of the truth for personal and ideological gain, few in the history of the assassination story have managed to crawl as low as Mark Lane".

My sincere thanks for taking the time to produce such a superb piece.

Barry Ryder

London

I read your book old-ver and new-ver again and again.

From few month before,I read and analyzed

"Rush to judgment" transcript from this film

(no cut ver? or director's cut ver?).

Mark Lane's method is worst,why assassination reserch

community member don't explain his fabrication?

In past,few resercher blamed his fabricaton method

(Gus Russo,Posner,Jean Division,Late Vincent Bugliosi,

Jim Moore,You).

But all is anti-conspiracy side.

So-called "Assassination resercher" used new

declassified material,but their disliked

"Rush to judgment" no cut transcript.

I't sad thing.

Hideji OKina

Japan

1. It matters little to me if Mark Lane used leading questions. So what? The testimony still has to hold up over time. Is there any evidence that a leading question produces bad testimony.

2. Interviewing people can be a chore. Perhaps Mark Lane and his people didn't have all day to wait for Ms. Clemons to get to the essence of what she had told them previously. Sometimes a leading question can save time. It doesn't necessarily follow that the testimony is in error.

3. Why would Mark Lane care whether there was an accomplice or not if there was already testimony indicating that the shooter might not be Oswald? Shouldn't we give Mark Lane some credit for being an attorney? Wouldn't a good attorney know that it's better to follow the truth; that the truth might help our case; and that our own foolish desires can come back to haunt us?

4. Why would Mark Lane care whether Lee Oswald killed Tippit or not? An experienced attorney would know that exonerating Oswald for Tippit's murder in no way exonerates Oswald for JFK murder.

5. Perhaps Mark Lane was a bit overzealous. Some of us can't tolerate lies; it get us worked up.

6. Everything considered, didn't Mark Lane do more good than bad in interviewing these people? By putting these people on tape, I think he extended their lives.

7. If you really, really want to talk about leading testimony, why don't we look at the Warren Commission, specifically with regard to the bruises on Marina's face. Did you see a bruise on her face? Are you sure you didn't see a bruise on her face? Are you really, really, really sure you didn't see Lee beat her to a pulp? C'mon, one leading question is as good as another.

8. For the record, I do not believe that Lee Oswald shot JD Tippit. I do, however, believe he participated in the shooting of JFK.

9. Good piece.

Hi, 'Unknown'

leaving aside your views on Mark Lane, can I ask why you don't believe that Oswald shot J. D. Tippit?

The Dallas Police were confident enough to charge him with the murder, the Warren Commission concluded that he had committed it and the HSCA reaffirmed the Warren Commissions conclusion.

What is it that causes you to doubt Oswald's guilt?

barry ryder

(London)

The FBI did NOT say it had "no record of Acquilla Clemons." It said it had no record of an Acquilla Clemmons/Plemmons/Klemmons/Clements [all misspellings] in any DALLAS file, further limited to those only containing the following two captions:

1. "JACK L. RUBY, Aka.; LEE HARVEY OSWALD, Aka (Deceased) - VICTIM, CIVIL RIGHTS"

2. "ASSASSINATION OF PRESIDENT JOHN FITZGERALD KENNED, 11/22/63, DALLAS, TEXAS, MISCELLANEOUS - INFORMATION CONCERNING"

By avoiding her real name (Acquilla Clemons - easily findable in the Dallas phone directory), and by limiting the "search" to only two document headers for files originating from only one field office, the FBI could legally evade the question.

There could have been literally hundreds of files on her with the subject header "ACQUILLA CLEMONS" and the FBI's denial of this witness, as worded, would have still been truthful (if you can call it that).

Anonymous – Wrong. The October 21, 1964, FBI Airtel, which you claim to quote, actually said: “No reference to one ACQUILLA CLEMMONS, or same first name with similar sounding surnames of PLEMMONS, KLEMMONS or CLEMENTS” were found in a search of Dallas FBI files (where they would surely be located if they existed). Get it? Similar sounding surnames would include variations in spellings, right? (But, oh Dale, they didn’t list all the variations.) No matter, Anonymous (who weakly and pathetically prefers not to sign his/her name, and stand behind their convictions), imagines that “hundreds of files on her” could exist in a “ACQUILLA CLEMONS” file stashed away in a secret FBI vault – or NOT, I presume. And pigs could be circling the moon. Who really knows?

Post a Comment