A previously unknown witness to the Dallas policeman’s killing tells her story

|

Emory Austin in 1960 and his daughter Mary, at age 16. (Graphic: © 2020 Dale K. Myers)

By DALE K. MYERS

The daughter of an Oak Cliff grocery store manager, who witnessed the immediate aftermath of the murder of Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit fifty-seven years ago, has revealed details about what happened that day.

Family members have been aware of twelve-year-old Mary J. Little’s account of the Tippit shooting story, but few others knew of her existence or that her story might color the world’s perception of another eyewitness – Acquilla Clemons, the star of Mark Lane’s book and film Rush to Judgment.

My encounter with Mary occurred by chance, as I pursued the truth about a wallet turned over to police on November 22, 1963 – a wallet that was later alleged to have been dropped by Tippit’s killer, Lee Harvey Oswald.

Three official inquiries into the Tippit murder, conducted by the 1963 Dallas Police Department, the 1964 Warren Commission, and the 1978 House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), concluded that Oswald was responsible for Tippit’s death. My own 25-year-plus investigation, detailed in my 1998 book, With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, confirmed their findings.

Exploring a loose end

Like most murder investigations, there are loose ends. The wallet story, exhaustively examined in With Malice, is one of those. Despite conclusive evidence that the wallet recovered at the Tippit scene was not the wallet removed from Oswald’s trouser pocket following his arrest at the Texas Theater, I was unable to determine the wallet’s origin. Nor has anyone else.

In 2009, eleven years after With Malice was published, former Dallas police officer Kenneth H. Croy told me that an unidentified white male gave him the wallet and said he found it “in the shrubs” (the exact location not further described). [1]

I had long suspected that the recovered wallet might not have had anything to do with the Tippit shooting, but instead might have been connected with an automobile accident that occurred at the corner of Tenth and Patton the morning of the assassination.

Back in March, 1996, I traveled to Dallas, Texas, with research companion Todd W. Vaughan. We spent two days going through the recently opened Dallas Police Department files on the JFK assassination. Today, the majority of these previously unpublished materials are available on-line. [2]

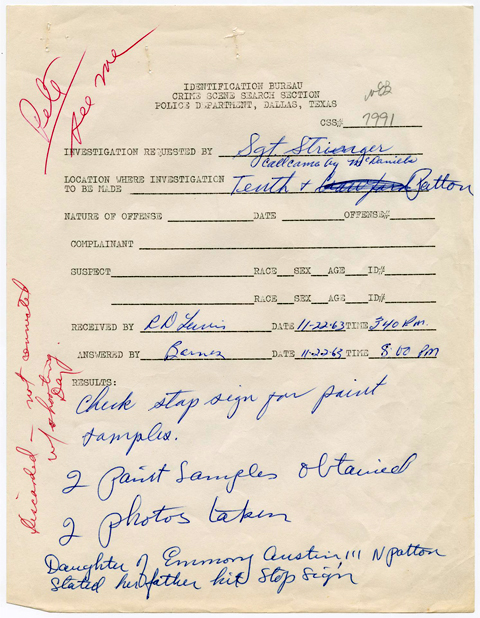

Among the documents and photographs in the police archive, we found a number of Crime Scene Search Section (CSS) forms relating to the Tippit case.

One such form was a request to check the stop sign at Tenth and Patton for paint samples. The request was answered by Sgt. W.E. “Pete” Barnes who took two paint samples and two photographs of the stop sign. The notation at the bottom of the form stated: “Daughter of Emory Austin, 111 N. Patton, stated her father hit the stop sign” and “Discarded – not connected w/ shooting – [J.C.] Day.” [3]

|

Fig.1 - Dallas Police Crime Scene Search Form regarding the stop sign.

Two years later, in my book With Malice, I made the link between a series of early police reports that an automobile might have been connected with Tippit’s death and the stop sign flattened by Emory Austin. Police eventually figured out that the early reports of an automobile and the stop sign had nothing to do with the murder. [4]

Flash forward to 2009 when Kenneth Croy told me that the wallet with the mysterious origin had been recovered “in the shrubs.” I recalled that Virginia Ruth Davis, an eyewitness to Oswald’s flight from the shooting scene, told me that the automobile that flattened the stop sign had careened through the shrubs on their property and struck the corner of their porch at 400 E. Tenth.

I began to wonder if the wallet recovered from “the shrubs” belonged to Emory Austin and had been “lost” at the accident scene earlier that morning?

Unfortunately, Emory W. Austin had died in 2003. However, I soon discovered that his daughter Mary – the one apparently mentioned on the Dallas Police Crime Scene Search form – was still alive and well. What I didn’t expect to find was that she had witnessed the Tippit shooting aftermath.

Here, presented for the first time, is what I discovered during my efforts to uncover the truth about Emory Austin, the accident that occurred on November 22, 1963, and what Mary Little saw that day.

Emory W. Austin, a legendary grocer

Emory Walls Austin (1929-2003) was a legend in the grocery business in Oak Cliff, having worked for Minyard’s Food Stores and the Safeway Food chain all his life. He was considered ‘family’ by the Minyard family, who even attended the funerals of both Emory W. Austin, and his wife, Dorothy.

Mr. Austin was a great story-teller who could get his point-of-view across using facts. He had been bald since his thirties and looked the same almost his entire life.

Every time a documentary or movie about the Tippit shooting appeared on television, Mr. Austin would complain that the re-enactment didn’t show the stop sign knocked down on the southeast corner of Tenth and Patton. He was heard to say on many occasions, “I had to buy that damn stop sign!” [5]

Emory W. Austin married Dorothy J. Little on September 3, 1963. [6] She had five daughters from a previous marriage, two of them were married. The oldest of the three remaining children was Mary.

The Little’s were living in Carrollton, Texas, just north of Dallas in the summer of 1963. Mary had just made the cheerleading squad at DeWitt Perry Junior High School when her mother announced that she and Emory were planning to get married in the early fall and that they would be moving. [7]

Emory had been awarded the branch manager job at Minyard’s Food Store in Lancaster, Texas, just south of Dallas. Opened in 1959, the Lancaster store was the largest grocery store in Minyard’s chain and the crown-jewel of its grocery empire. [8] Emory and Dorothy knew that they would have to find a place to live that was closer to the Lancaster store than either of their current residences.

In August, 1963, they leased the house at 111 N. Patton, just north of Tenth Street in Oak Cliff. Mary was disappointed that she couldn’t continue to live in Carrollton, attend school with her friends, and would miss the chance to be on the cheerleading squad which she had worked so hard to join. [9]

She was enrolled at James Bowie Elementary School, 301 N. Lancaster, as were her two younger siblings, Bobbie and Debbie.

November 22, 1963

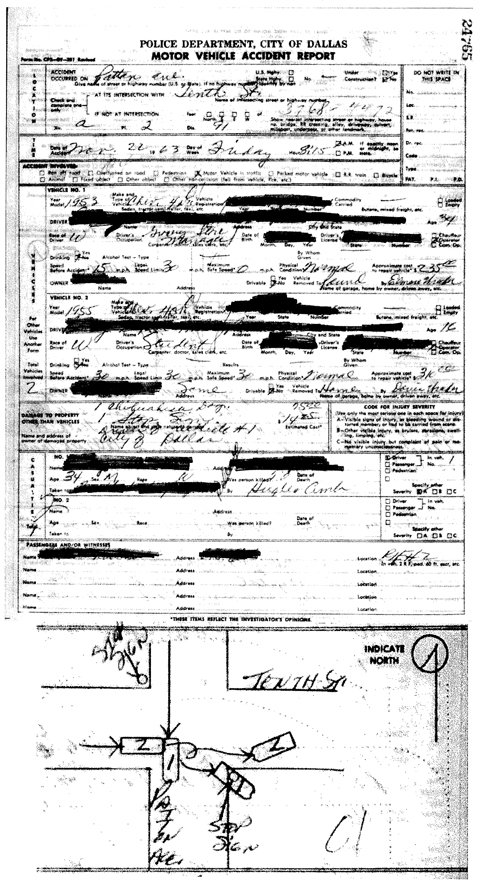

On the morning of November 22, 1963, at 8:15 a.m., Emory Austin, age 34, left the family home on Patton driving his 1953 Chevrolet four-door sedan, heading south. He apparently ran the stop sign at the intersection of Tenth and Patton and was struck on the right-rear quarter panel by a 1955 Chevrolet four-door heading east on Tenth at 30 m.p.h. [10]

The impact drove the Austin automobile into the stop sign on the southeast corner, flattening the sign. According to Virginia Ruth Davis, age 16, and Mrs. Acquilla E. Clemons, age about 30, the Austin automobile not only flattened the stop sign, but careened through the shrubs and struck the northwest corner of the front porch of the Davis home at 400 E. Tenth Street. [11]

|

Fig.2 - Dallas Police photograph of the stop sign flattened by Emory Austin's car.

Upon impact, Mr. Austin’s head struck the windshield and he sustained severe head injuries. The crash also caused the passenger door of his vehicle to popped open and the family dog, a Chihuahua named ‘Tiki-Tico’, was flung from the car and killed. [12]

Emory’s car was totaled. The car that struck the Austin vehicle was driven by a 16-year-old local student, who was not injured. Both vehicles were later towed. [13]

Mr. Austin was ticketed for the accident, and had to pay for a new stop sign that was later erected at the location, as part of his restitution. [14]

|

Fig.3 - Dallas Police Department Accident Report with diagram. (DPD Archives / Courtesy of Steve Roe).

Emory was rushed to Methodist Hospital, by Dudley M. Hughes ambulance service. [15] The accident occurred in Dallas police district No.91, which was patrolled that morning by Officer William D. Mentzel (Unit 91). The accident investigator who responded to the scene was Vernon R. Nolan (Unit 222). Both officers later responded to the Tippit shooting. [16]

Emory’s wife, Dorothy, accompanied him to the hospital. A steel plate was put into Mr. Austin’s skull and his head was bandaged. Dorothy telephoned Minyard’s Food Store (No.9), at 919 N. Dallas Ave., (TX-Hwy 342), Lancaster, TX., informed them of the accident, and asked one of Emory’s fellow employees to come to the hospital in his vehicle. He drove to the hospital and took Mr. and Mrs. Austin back to their home on Patton Avenue. [17]

Dorothy made arrangements with the employee to borrow his car for a few days, since the Emory’s car had been totaled in the accident. She and the grocery store employee then drove to James Bowie Elementary School around noon, and picked up her daughter Mary from school. [18]

Dorothy, wanted her daughter to sit with Emory, while she drove the Minyard’s employee back to the food store in Lancaster, Texas, and then returned in his borrowed car. She would be gone about an hour.

Because Mary, at age twelve, was the oldest of the three daughters still living at home, she was selected to stay with her step-father to keep him talking and awake. The hospital didn’t want him sleeping because of the concussion he sustained in the accident.

The shooting

Mary told me that at around 1:00 p.m. she was sitting at the dining room table with her step-father, passing the time.

“I was twelve years old,” she said, “and he was teaching me how to give change because he wanted me to be a cashier at his store someday. He had all this change out and said, ‘If your bill was two dollars and ninety-seven cents and you had three dollars, how much money would you give them back?’ and stuff like that.” [19]

Mrs. Austin was gone just a short time, when, they heard two loud POPS. Mary made a remark about the sound being firecrackers or a backfire, but Emory said, “No, that’s not a backfire.”

Mary said, “Really?”

Her step-father reiterated, “No, that’s not a backfire. That was gunfire.” [20]

Mary ran out the front door and saw a black maid approaching the northwest corner of Tenth and Patton from the west.

Mary ran up to her. She was bawling and taking the white apron she was wearing and wringing her hands with it, saying, “Oh my god! Oh my god! What’s happening? First the president and now this!” This was the first Mary heard that the president had been shot. [21]

Mary told me that she looked to her left and saw a police car. The door of the squad car was wide open and a policeman was laying near the left front tire. She later said that once she arrived at the corner of Tenth and Patton, she was focused on the police car to her left and that had she simply turned to look south down Patton, she might have seen Lee Harvey Oswald making his escape. [22]

Mary walked toward the police car parked further down Tenth Street, adding that the black maid never crossed Patton to get any closer to the car but instead remained on the northwest corner of Tenth and Patton. [23]

As the twelve-year-old approached the fallen officer, she saw a bullet wound in his right temple, but no other wounds. The wound in the temple had a trickle of blood coming from it. [24]

A lady came out of a white, wooden two-story house, located directly across the street from the police car, carrying a blanket. She said, “Oh my god! Oh my god! Just throw this over him! Throw it over him!” The woman then retreated to her home. [25]

Suddenly a white man appeared on the scene, coming from the east end of the block, but that was all she remembered about him. [26] She didn’t see anyone using the police radio [27] or any other people at the scene other than the three she described – the black maid, the woman with the blanket, and the man. Mary believed she was the third person to arrive on the scene. [28]

After throwing the blanket over the officer, she returned to the corner where the black maid was still standing. It was not clear if her conversation with the maid occurred before she ran to the officer or after. But Mary did say that she saw the black maid go back to the house on Tenth Street where she was taking care of an elderly man and woman (which suggests that she had further conversation with the maid before she left the corner).

Mary said that the house that the black maid returned to was the second one west of the intersection of Tenth and Patton and that it was located on the north side of the street. [29]

Acquilla Clemons, reluctant witness

Anyone familiar with the Tippit shooting story knows that the location described by Mary Little was the home of John B. and Cornelia M. Smotherman, who lived at 327 E. Tenth – two houses west of the corner of Tenth and Patton, on the north side of the street. [30]

The “maid” was no doubt Mrs. Acquilla E. Clemons who told Oklahoma housewife Shirley Martin, in a secretly recorded interview in early July, 1964, that there had been a car wreck on the corner of Tenth and Patton the morning of the Tippit shooting and that a little dog was killed – an obvious reference to the Emory Austin accident. [31]

Mrs. Clemons went on to tell Martin that after she heard gunshots, she ran down to the scene of the Tippit shooting, “I went down there and looked at [Tippit], but I don’t know. I forgot – it was just an upset day. I couldn’t think. All I know somebody got up in that car to call the police. I went to the door to call the police and I couldn’t get in. I had left [Mr. Smotherman] – and I don’t know who, I don’t know how they got them [the police]. Somebody called them on the police car. I don’t know who it was ‘cause I had to come back here. [Mr. Smotherman] was very sick. I didn’t pay anything – any attention ‘cause I was just looking. ‘Cause [Mr. Smotherman] was awful sick and I had to go.” [32]

Mrs. Clemons told Mark Lane in 1966, “I ran back down the street where he was lying, and I looked at him. I had to go back to the house; I had a patient.” [33]

Mrs. Clemons’ claim that she walked down to the car is contrary, of course, to what Mary Little witnessed. Mary said the black maid was too scared to get closer than the corner and never crossed Patton Avenue.

George and Patricia Nash, who also interviewed Acquilla Clemons in early July, 1964, later wrote in The New Leader: “Her version of the slaying was rather vague, and she may have based her story on second-hand accounts of others at the scene.” [34]

Mary told me that she would definitely recognize a photo of the black maid and that it was unusual at that time for black people to be in the area and that most people in that neighborhood couldn’t afford to have a maid. Asked how old she thought the black maid was, Mary stated, “Oh, she was probably in her sixties.” [35]

When shown an image of Acquilla Clemons (as she appeared in the 1966 film Rush to Judgment), Mary told me that this was not the woman she remembered, describing the black maid she encountered as being of medium height and weight. [36] Although her exact age is unknown, Mrs. Clemons appears to be heavy-set and about 30 years of age.

It’s hard to imagine, given all of the circumstances, that the black maid Mary encountered was not Acquilla Clemons, despite Mary’s inability to identify her by photograph nearly sixty-years after their brief encounter. After all, Mary was only twelve at the time, and by her own admission had never seen the maid before or since.

A policeman’s been shot!

Mary told me that she returned to her house and told her step-father, Emory Austin, that an officer had been shot and that the president also had been shot. She told him that she had learned this from a black maid who worked in a house on Tenth Street, and whose property backed up to their own backyard. Emory instructed Mary to turn on the television. [37]

Mary said that she had left the Tippit scene and returned to her house before the ambulance arrived to take Tippit to Methodist Hospital. Shortly thereafter, the neighborhood was filled with “hundreds of policemen”, many on motorcycles, who were searching backyards and ordering citizens to remain indoors. Mary stated that she observed much of this from her front porch. [38]

During this period, police radio broadcasts linking an automobile to the Tippit shooting were being picked up by the news media. By early afternoon, NBC affiliate WBAP-TV in Fort Worth was reporting that “Tippit was shot to death by an unknown man in a car.” [39]

A Dallas Times Herald article about Tippit’s death quoted a Dallas Police investigator as saying, “There may be a tie-in [between the JFK and Tippit slayings]. On a thing like this we have to check everything. We have a report the fellow that did the shooting of the policeman had a rifle in a car with him.” [40]

Sergeant Gerald L. Hill elaborated on the connection of an automobile with Tippit’s murder during an NBC television interview.

“I am convinced that the man we have is the man that shot the officer. As to the circumstances that happened prior to the shooting, we can only surmise that the officer stopped a car, on possibly a traffic violation or on information from a citizen, but we can’t verify that, and also, the only two people that can tell us why the officer stopped him is the officer and the man who shot him.” [41]

Lt. Jack Revill told a radio reporter something nearly identical during a telephone interview at 3:30 p.m. on November 22, 1963:

Reporter: What were the circumstances when he killed the officer?Revill: Ah, I’m not familiar – too familiar with it, I think it was a traffic violation.Reporter: I see.Revill: He killed the officer – shot him – a couple of times. [42]

These early police reports no doubt stemmed from information broadcast over the police radio that described how a station wagon with a “rifle laying in the backseat” was seen heading toward central Oak Cliff and that a citizen was following the car. Later, the same car was reported by the Sheriff’s radio dispatcher to be in the vicinity of West Jefferson, a few blocks from the Tippit shooting scene.

It may have been in response to those reports that Dallas Police Crime Lab photographer Sgt. W.E. “Pete” Barnes snapped a photograph of a stop sign that had been knocked down at the corner of Tenth and Patton.

“We had a report that we thought maybe [the stop sign] might have had some significance on the case,” Sgt. Barnes told the Warren Commission. [43]

This appears to dovetail with Sgt. Hill and Lt. Revill’s remarks that Tippit may have stopped a car due to “a traffic violation.”

Later investigation, revealed that the stop sign was knocked down during the morning traffic accident involving Emory Austin. However, early in the investigation, police may have suspected that Tippit had stopped a car that failed to yield to traffic.

The lost story

Mary told me that prior to my call she had only talked to three people about what she saw.

The first time occurred on the evening of November 22nd, around 6:00 p.m. A photographer identified to her as being from Germany, was escorted to her front door by neighborhood children who were telling him that “She saw it all!”

He asked her to come out and point to the spot where Tippit was laying in the street. The photographer slipped her a twenty-dollar bill for her trouble – a sizeable amount in those days.

She stated that she took him over to Tenth Street and dutifully pointed out the location, though, she said, there was no blood that marked the spot. (The only blood she ever remembered seeing was the trickle coming from Tippit’s right temple.) [44]

No such photograph ever surfaced in any United States publication that I am aware of. Whether a German publication published the photograph that Mary recalls is unknown.

The second time she was approached was between the early 1970s and 1980s. Mary recalled that on that occasion two men who claimed to be writing a book approached her for her story. They had found her through her step-father, Emory Austin. They tracked him down to where he was working and approached him for his story. He told them he never left the house because of his concussion and that his daughter could tell them whatever they wanted to know. He then gave them her phone number.

They located her and after she told her story, they pulled out an album of photographs. While looking through them, she spotted a photograph of the stop sign knocked down and told them, “Oh, there’s the stop sign that my step-father hit in a wreck.”

They expressed surprise, as if this was a revelation to them, even remarking, “Well, we thought it was trampled down by the police,” which Mary found quite amusing. [45]

Mary said that she hadn’t read anything about the Tippit shooting in the intervening years and had only talked to the three people she mentioned before she spoke to me – the German photographer and the two men writing a book.

This was a good thing. It meant that her recollections were fresh – at least as fresh as a nearly sixty-year-old memory can be. I found her remarkably sharp at age seventy. She was candid and like most truth-tellers didn’t embellish her account where she could have. I heard a lot of “I don’t knows” and “I don’t recalls” over the course of our conversations.

Her mis-recollections (based on a comparison with other accounts) were minor and understandable under the circumstances. Her reported “tunnel-vision” (recalling only what was directly in front of her) is a physiological manifestation typical of people in high-stress situations. [46]

Obviously, it would have been much better if we had heard her story in 1963. Still, I found her belated account quite credible.

What about the wallet?

I hadn’t forgotten why I tracked down Mary in the first place. Asked whether her step-father might have lost his wallet at the accident scene, Mary said that she didn’t think so, “No, I don’t remember him saying, ‘Oh my gosh, I’ve lost my wallet’ or anything like that.” [47]

Two other family members were also asked about a missing wallet, but none of them had heard any such story. [48]

I often wondered how police determined that Emory Austin was the person responsible for knocking down the stop sign at Tenth and Patton. Of course, there would have been a police report of the accident, a record of the ambulance run, and a towing company that removed the wrecked vehicles from the scene – all of those records long ago discarded. [49]

With a simple phone call or two, the Dallas police could have determined from official records that the stop sign was knocked down earlier that morning and that the person responsible was Emory Austin.

On the other hand, someone could have found Emory Austin’s wallet laying in the shrubs after it was blown out the passenger door with the family dog. They could have turned it over to police, thinking it might have something to do with the Tippit shooting.

Checking the wallet’s identification would have led police to the house at 111 N. Patton, where Mary, or one of Emory’s other step-daughters, could have told police, ‘Yes, it’s my step-father’s wallet. The flattened stop sign was his fault.”

What I found most curious was what Sgt. “Pete” Barnes wrote on the bottom of the Dallas Police Department Crime Scene Search (CSS) form found in the Dallas police archives in 1996.

He didn’t write that he made a phone call and determined from the radio dispatcher’s office that police had made an accident run earlier that day, or that the Dudley M. Hughes ambulance service responded to an accident at that location earlier that morning, or that a tow truck company dragged two wrecked vehicles away from that location shortly before the Tippit shooting.

No, Sergeant Barnes wrote, “Daughter of Emory Austin, 111 N. Patton, stated her father hit the stop sign,” as if the daughter was the source of the information.

I told Mary about the Dallas Police Department Crime Scene Search (CSS) form and read the notation written at the bottom of the form to her. I asked her if she recalled having any contact with the police following the Tippit shooting or whether they came over to the house afterwards? Mary said, “No,” she didn’t remember anything like that. [50]

Since Mary Little was a minor at the time, I thought that perhaps the daughter referred to in the notation wasn’t Mary at all, but one of her two older sisters. I determined that only one – her oldest sister, age 19 and recently married – was living in Texas in 1963.

I telephoned her and she confirmed that she did in fact drive over to her mother and step-father’s house on Patton during the evening hours of November 22, 1963. I asked her if she knew how the police connected the Austin family with the flattened stop sign? She didn’t know. Clearly, she wasn’t the one that talked to police.

Did her sister Mary tell police? “I don’t know,” she said. “I think she did, but I’m just guessing what she did. She told us everything. We were there and everything afterwards, but I don’t know the whole details.” [51]

If Mary Little did talk to police in the early evening of November 22, 1963, she had long ago forgotten.

Later, Mary’s oldest sister told me, “It’s too bad you didn’t try to find this out earlier. Of course, my step-dad died about fifteen years ago. My mom died twenty-seven years ago. But they would have been able to tell you everything.”

Yes, too bad.

Unconnected dots

Unfortunately, I had reached the end of the trail. Fifty-seven years after the fact, no one is alive who remembers how police made the connection between Emory Austin and the damaged stop sign.

If Emory Austin’s wallet was found “in the shrubs” and turned over to police, no one alive remembers it that way. Certainly, there’s nothing to suggest that it did happen that way, other than wishful thinking and a string of unconnected dots.

But then, stranger things have happened in the case that never seems to end. [END]

[1] Memorandum to file, Kenneth H. Croy, RE: Wallet chain of custody, August 5, 2009, pp.1-3

[2] Memorandum, Dallas Trip, March 13-15, 1996, pp.1-12

[3] CCS Form for Investigation of Stop Sign - https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth339551/m1/1/

[4] Myers, Dale K., With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, (Oak Cliff Press, Inc., 1998), pp. 210-211; (2013 edition, pp.271-272)

[5] Telephone conversation, Dale K. Myers with Austin family member, August 4, 2020, p.3

[6] State of Texas, Marriage Record No.205908

[7] Interview of Mary J. Little, September 1, 2020, pp.8-9

[8] “Opening Set in Lancaster by Minyard’s”, Dallas Morning News, June 28, 1959, Section 4, p.3

[9] Interview of Mary J. Little, September 1, 2020, pp.8-9

[10] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp. 4-8; Dallas Police

Department, Motor Vehicle Accident Report, No.24765, November 22, 1963, pp.1-2

[Note: Mary told me that Mr. Austin drove his two youngest step-daughters – Bobbie,

age 10, and Debbie, age 8 – to James Bowie Elementary School, at around 8:30

a.m. and was returning to their house on Patton, via Jefferson Boulevard, when

he ran the stop sign at Tenth and Patton and was hit broadside on the driver’s side.

The accident report, retrieved by researcher Steve Roe, shows different

circumstances.]

[11] Interview of Virginia Ruth Davis, July 11, 1997, p.7; Interview of Acquilla E. Clemons by Shirley Martin, 1964, p.4

[12] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp. 4-5; Interview of Acquilla E. Clemons by Shirley Martin, 1964, p.5

[13] Telephone conversation, Dale K. Myers with Austin family member, August 4, 2020, p.5, 10;

Dallas Police

Department, Motor Vehicle Accident Report, No.24765, November 22, 1963, pp.1-2

[14] Telephone conversation,

Dale K. Myers with Austin family member, August 4, 2020, p.3; Dallas Police

Department, Motor Vehicle Accident Report, No.24765, November 22, 1963, p.2

[Note: Austin’s court date was set for December 9, 1963 at 2:00 p.m. Estimated

cost of a replacement for the stop sign: $14.75.]

[15] Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, p.3; Telephone conversation, Dale K. Myers with Austin family member, August 4, 2020, 1:23 p.m., p.3

[16] Review of Dallas Police Department radio transmissions, Channel One and Two, November 22, 1963; Dallas Police Department, Motor Vehicle Accident Report, No.24765, November 22, 1963, p.2 [Note: Officer Nolan received the call for the accident at 8:22 a.m. and was on-scene at 8:27 a.m.]

[16] Review of Dallas Police Department radio transmissions, Channel One and Two, November 22, 1963; Dallas Police Department, Motor Vehicle Accident Report, No.24765, November 22, 1963, p.2 [Note: Officer Nolan received the call for the accident at 8:22 a.m. and was on-scene at 8:27 a.m.]

[17] Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, pp.5-6

[18] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.7; Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, p.4

[19] Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, pp.6-7

[20] Ibid., p.7

[21] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.9, 26; Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, p.7

[22] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.12, 13

[23] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.9, 34

[24] Ibid., p.3

[25] Ibid., p.4

[26] Ibid., pp.9-10

[27] Ibid., p.14

[28] Ibid., p.10

[29] Ibid., p.34

[30] Smotherman, John B., obituary, Dallas Morning News, December 22, 1966, Section D, p.5; Polk’s Greater Dallas City Directory, 1963-1966, Street Index, p.8, Name Index (1964), p.1461

[31] Interview of Acquilla E. Clemons by Shirley Martin, 1964, pp.3-5

[32] Ibid., p.3

[33] Interview of Acquilla E. Clemons by Mark Lane, March 23, 1966, p.1, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Emile De Antonio, Box 61, Folder 4, Clemons Interview

[34] Nash, George and Patricia, “The Other Witnesses,” The New Leader, October 12, 1964, FBI 62-109090 Warren Commission HQ File, Section 24, pp.139-143

[35] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.34

[36] Interview of Mary J. Little, September 1, 2020, p.2

[37] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.28

[38] Ibid., pp.4, 15

[39] WBAP-TV, Ft. Worth, NBC News, Charles Murphy reporting, 1:49 p.m. CST (A&E’s “As It Happened”, NBC-TV coverage rebroadcast 11-22-88)

[40] “JFK, Patrolman Killing Linked,” Dallas Times Herald, November 23, 1963, Section A, p.19

[41] CE2160, p.4, (24H805) [Note: In a 1986 interview, Hill told me that he might have said that Tippit stopped a car while “trying to think fast enough” during the television interview, but that he had “no information to base that on.” The record, however, shows a considerable amount of information that parallels the essence of Hill’s remarks. (Author’s interview of Gerald L. Hill, October 30, 1986, pp.18-19)]

[42] Interview of Jack Revill by Don Michel, WRAJ 1440-AM, Anna, Union Co., IL, November 22, 1963, 3:30 p.m.

[43] 7H273 (WCT of W.E. Barnes, April 7, 1964)

[44] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp.15-17 [NOTE: Contrary to Mary’s statement, a blood splatter pool, still visible in the street, was filmed by a WBAP-TV (NBC) news crew the next morning.]

[45] Ibid., pp.17-19

[46] https://psychology-spot.com/tunnel-vision-anxiety-stress-psychology/

[47] Ibid., p.24

[48] Telephone conversation, Dale K. Myers with Austin family members, August 4, 2020, 1:23 p.m., pp.2-3; 2:07 p.m., p.10

[49] Police departments typically retain accident reports for a period of five to seven years and then they are routinely purged from their files.

[50] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp.22-24

[51] Interview of Patricia J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp.3-4

[18] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.7; Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, p.4

[19] Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, pp.6-7

[20] Ibid., p.7

[21] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.9, 26; Interview of Mary J. Little, August 4, 2020, p.7

[22] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.12, 13

[23] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.9, 34

[24] Ibid., p.3

[25] Ibid., p.4

[26] Ibid., pp.9-10

[27] Ibid., p.14

[28] Ibid., p.10

[29] Ibid., p.34

[30] Smotherman, John B., obituary, Dallas Morning News, December 22, 1966, Section D, p.5; Polk’s Greater Dallas City Directory, 1963-1966, Street Index, p.8, Name Index (1964), p.1461

[31] Interview of Acquilla E. Clemons by Shirley Martin, 1964, pp.3-5

[32] Ibid., p.3

[33] Interview of Acquilla E. Clemons by Mark Lane, March 23, 1966, p.1, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Emile De Antonio, Box 61, Folder 4, Clemons Interview

[34] Nash, George and Patricia, “The Other Witnesses,” The New Leader, October 12, 1964, FBI 62-109090 Warren Commission HQ File, Section 24, pp.139-143

[35] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.34

[36] Interview of Mary J. Little, September 1, 2020, p.2

[37] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, p.28

[38] Ibid., pp.4, 15

[39] WBAP-TV, Ft. Worth, NBC News, Charles Murphy reporting, 1:49 p.m. CST (A&E’s “As It Happened”, NBC-TV coverage rebroadcast 11-22-88)

[40] “JFK, Patrolman Killing Linked,” Dallas Times Herald, November 23, 1963, Section A, p.19

[41] CE2160, p.4, (24H805) [Note: In a 1986 interview, Hill told me that he might have said that Tippit stopped a car while “trying to think fast enough” during the television interview, but that he had “no information to base that on.” The record, however, shows a considerable amount of information that parallels the essence of Hill’s remarks. (Author’s interview of Gerald L. Hill, October 30, 1986, pp.18-19)]

[42] Interview of Jack Revill by Don Michel, WRAJ 1440-AM, Anna, Union Co., IL, November 22, 1963, 3:30 p.m.

[43] 7H273 (WCT of W.E. Barnes, April 7, 1964)

[44] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp.15-17 [NOTE: Contrary to Mary’s statement, a blood splatter pool, still visible in the street, was filmed by a WBAP-TV (NBC) news crew the next morning.]

[45] Ibid., pp.17-19

[46] https://psychology-spot.com/tunnel-vision-anxiety-stress-psychology/

[47] Ibid., p.24

[48] Telephone conversation, Dale K. Myers with Austin family members, August 4, 2020, 1:23 p.m., pp.2-3; 2:07 p.m., p.10

[49] Police departments typically retain accident reports for a period of five to seven years and then they are routinely purged from their files.

[50] Interview of Mary J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp.22-24

[51] Interview of Patricia J. Little, July 8, 2020, pp.3-4

6 comments:

Excellent follow-up article. The only missing question for me is what happened to the wallet and did anyone make note of the contents. It wasn't Oswald's wallet, as some have alleged, but contents would confirm no connection to Oswald.

Good stuff, Dale. I bought and read your Tippit book about 5 years ago and I thought it was great. Now I think I will read it again!

Dale,

once again, full marks for some very tenacious research. I think that you may have now explored every legitimate and sensible line of enquiry regarding this perplexing issue. Your honesty in acknowledging that you’ve been unable to resolve it does you much credit. Too many lesser ‘researchers’ would have been unable to resist the temptation to fabricate a solution. As far as I’m concerned, if you can’t resolve the ‘Oswald wallet’ mystery, nobody can.

Like most other folks who have mulled over this, I do have an opinion – of sorts. Having read all of the available material on the Tippit murder contained in the WC, HSCA, ‘With Malice’ and this excellent blog, I’m of the opinion that the wallet shown in WFAA-TV footage probably belonged to a witness at the scene. Why? Here goes:

1) None of the attending officers mentioned in their reports or testimony the discovery of a wallet at the scene – much less a wallet containing details of Oswald/Hidell. For me, this goes to the heart of the matter. There is no contemporaneous support for the discovery of a wallet.

2) Had such a thing been found, surely an APB would have been issued immediately. But – as you have noted – none was. Again, contemporaneous actions are at odds with later recollections.

3) No witness ever described a wallet as being near Tippit’s body (WM p. 299). All we have is a dubious hearsay connection that has no evidential support.

4) A wallet containing Oswald’s real and fake IDs would have been evidential gold-dust; I cannot conceive that this item could have been lost/misplaced by the crime-scene officers. In his book, Hosty writes that, “Westbrook took the wallet into his custody so that it could be placed into police property later.” There is no DPD or FBI documentation to show that this ever happened. There is no testimony to support it either.

5) The Reiland voice-over describes the revolver captured on film as being “..the one that was allegedly used to shoot the police officer.” As you note in WM p. 299, Reiland was wrong about that and that he, “..had made a number of factual errors while reporting news during the course of the weekend.” One of his many errors included describing billfold as being Tippit’s. It wasn’t, of course.

Frankly, I believe that both Barrett and Westbrook were wrong in what they later recalled. I think that the examination of the wallet and all discussion about it probably occurred at City Hall. Reiland may have sowed the seeds for this confusion and Hosty later gave the story an air of legitimacy.

Given all of the above, if pressed to say whose wallet was filmed, I’d say that it belonged to a witness and the officers were simply checking the ID within it. Had the wallet been found near Tippit’s body and had it contained the name and details of somebody who was not then at the scene, I feel sure that it would have been handled with far more urgency than is apparent in the WFAA-TV footage.

I cannot say that this happened, of course; this is merely my opinion.

Barry Ryder

I think we could be on to something -- was Tiki-Tico the dog that Jean Hill testified that she had seen in the JFK limo? But seriously, great work as always, Dale. It's crazy that these two things happened within just hours at the same place. I can't imagine how chaotic it must have been for everyone so it's great that she has retained the memory of what she saw after all these years.

Interesting. Never heard about this before. I have also never heard an explanation from those prone to believe the various conspiracy theories as to what happened to the curtain rods Oswald was alleged to have the morning of the assassination.

During his various interrogations, Oswald denied ever mentioning or carrying curtain rods. So, either Wes Frazier and Linnie Mae Randle made-up the 'curtain rod' story or Oswald's denial was untrue. Given what we know about Oswald, Frazer and Randle, it's easy to conclude that Oswald was lying and that Frazier and his sister were telling the truth about the package that they both saw and what it supposedly contained.

Post a Comment