|

The framed photograph from Jack Christopher’s night stand. (© 2022 DKM. All Rights Reserved.)

By DALE K. MYERS

Until his death in 2015, Jack Christopher kept a framed photograph of himself and his longtime best friend and brother-in-law, J.D. Tippit, on his bedroom night stand in Dallas.

The photo depicted the pair in happier times – 1946 to be exact – when Jack and J.D. first came to Dallas and lived together with their wives in a Hickory Street rented-flat.

Today, the house is long gone and the two smiling faces captured in silver halide crystals have faded from existence.

But the lives they lived and the stories that they told live on in the memories of surviving friends and family, though their numbers too are dwindling.

It’s been nearly sixty-years since J.D. Tippit, a 39-year-old Dallas police officer, was gunned down in a broad daylight shooting in Oak Cliff, just 45-minutes after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Twenty-four years ago, I wrote the book, “With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit,” in an effort to keep alive the memory of the fallen patrolman and bring some long-sought truth to the historic narrative surrounding Tippit’s death.

Ironically, the publication of “With Malice” led to an audience with the extended Tippit family, thanks largely to the daughters of Jack Christopher – Linda and Carol. Linda spotted a review of the book in The Dallas Morning News and urged her sister Carol to get a copy. After reading the book and recommending it to other family members, Carol posted a comment on Amazon.com. Soon thereafter, we met.

Over the course of the next year, I interviewed numerous family members and gained an insight into the family dynamics that had not been breeched before. It was an honor and a great privilege to be trusted with documenting and preserving the many trials and tribulations of the Tippit family.

Like any family, much of it is familiar ground. You recognize yourself and your own family in much of the retelling, though, of course, one can only imagine what it must have been like to have the life of one so-loved ripped away unexpectedly and then maligned by idiots and fools who claimed to know more about J.D. Tippit than his own family. Some even accused – and continue to accuse – the fallen patrolman of being part of the conspiracy they imagine was behind the Kennedy assassination. To many of them it’s just a parlor game; something to be played to fill the hours of a boorish life.

In 2013, with the family’s encouragement and blessing, I updated “With Malice” with 150-pages of new material gleaned largely from those 1999 family interviews and the many stories I had been told since then.

Those family accounts placed the tragedy of November 22, 1963 – a very personal one for the Tippit family – into perspective. The late Joyce DeBord, the youngest sister of J.D. Tippit, was so happy to see her brother’s life story – the true story – finally in print. I was happy to do it, and to be honest, I did it largely for her.

But I also knew that with the addition of the family perspective, “With Malice” would become the rock upon which the historic narrative of the Tippit murder would be evaluated. And thankfully, despite attempts to derail it, that has turned out to be true.

Of course, I’m not naïve enough to think that everyone would accept that truth.

By the fiftieth anniversary, when the updated edition of “With Malice” was released, I had come to realize that there would always be a small cabal of detractors who would never accept the fact that J.D. Tippit was just a country boy turned policeman who was cut down in a hail of bullets by an avowed Marxist who had no regard for anyone but himself.

If there is anything that is certain nearly sixty-years after the events of Dallas it is this – J.D. Tippit was not part of some vast conspiracy to kill Kennedy or murder his accused assassin. And yes, Lee Harvey Oswald murdered him.

But then, we’ve really known that from the start, haven’t we?

An unusual killing

Forty-five minutes after the assassination of President Kennedy, a citizen’s voice blared over the Dallas police radio.

“Hello, police operator? We’ve had a shooting out here.” [1]

T.F. Bowley, who happened upon the scene, told the dispatcher that the shooting involved a police officer in Oak Cliff.

Dallas police officers, who had surrounded the Texas School Book Depository in search of the presidential assassin, instantly recognized the shooting of one of their own as an unusual event.

In today’s world, a police shooting is sadly not unusual at all. But in November, 1963, the vast majority of the nation’s populace held law enforcement in high regard. And Dallas was no different.

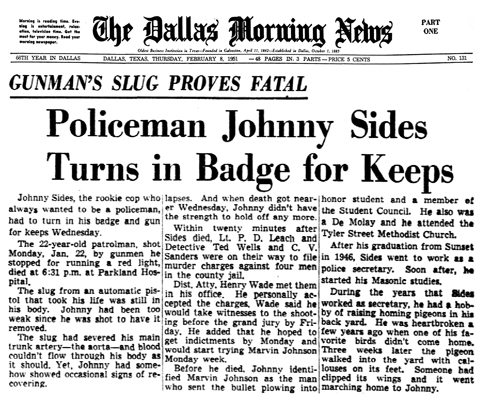

In fact, when Tippit was killed, it had been more than 12-years since the last uniformed Dallas patrolman, Johnny W. Sides, 22, had been shot down in a Dallas street. Sides and his partner, Harold L. Dawson, had stopped a car for running a red light. Dawson was also wounded in the shooting. Sides died two days later at Parkland Hospital. [2]

|

FIG.1 – Front page story, Johnny W. Sides killed. (DMN)

And, it would be five more years before another Dallas policeman lost his life due to gunfire – Patrolman Floyd A. Knight, 23, who was shot in the face by a holdup man while guarding a 7-Eleven store in Oak Cliff. [3]

So, yes, it was unusual for a uniformed Dallas policeman to be shot in broad daylight in 1963; and doubly suspicious that it happened just 45-minutes after the presidential assassination and only 2.5 miles away.

Captain W. R. Westbrook, who was one of many officers who raced to the Tippit shooting scene, immediately thought the president’s assassination and the Tippit shooting were connected.

“It was immediately in everybody’s mind [that the shootings] was connected,” Westbrook told researcher Larry A. Sneed in 1986. “That was my thought. That was everybody’s thought; that the same person probably was [responsible] – that the two happened just [a few miles] apart – and that Tippit had run across the man who had done the [presidential] shooting.”

Pressed as to why he thought the two shootings were linked, Westbrook quipped, “Because I am a human, I guess.”

“Was it your intuition?” Sneed asked.

“Well, no, it was just – well intuition or whatever,” Westbrook answered. “But you have a president killed and a few minutes later you have an officer shot within a couple of miles, you’re going to think they’re connected. I mean, a person that doesn’t think they’re connected is an idiot!” Westbrook laughed, then grew more serious.

“Maybe they’re not really [an idiot],” Westbrook continued, “but that’s going to be his first thought. If it’s not, he’s not normal.” [4]

In short, if you’re a cop in Dallas in 1963 and you’ve been paying attention to what’s going on, you’re bound to think that the two shootings are connected somehow. And a lot of officers who responded to the Tippit shooting did think the two shootings had to be connected. Of course, there wasn’t any concrete evidence at that point to back up those feelings, but it was a normal, gut reaction to the situation. And why wouldn’t it be?

And yet, nearly sixty-years later, a procession of Internet trolls with no law enforcement experience find nothing unusual about the back-to-back shootings in Dallas that day. Certainly nothing that connects Lee Harvey Oswald to either shooting. Instead, they speculate that perhaps W.R. Westbrook himself is yet another participant in the big, imagined conspiracy. Of course.

Brushing the nonsense aside, it only takes a cursory look at the events as they unfolded in real time to realize who was responsible for Tippit’s death.

|

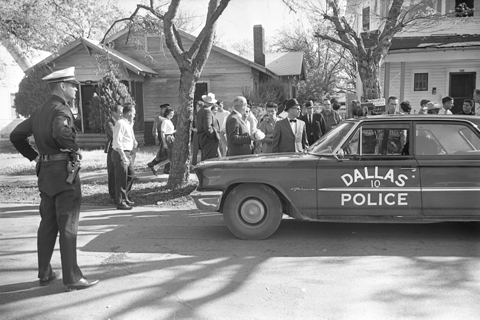

FIG.2 – Tippit crime scene at 1:44 p.m. (Darryl Heikes, Dallas Times Herald Collection/The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza)

The crime scene

When police arrived en mass at the shooting scene, just eight minutes after the slaying, they found seven eyewitnesses (who either saw the shooting or saw the gunman fleeing), some physical evidence, and a suspect on the loose.

One witness – Helen Markham – saw the entire shooting unfold start to finish. Two others, in close proximity – mechanic Domingo Benavides and cab driver William W. Scoggins – saw portions of the shooting and watched as the killer fled south on Patton Avenue. Two young women, Barbara and Virginia Davis, living in the corner house, watched the shooter cut across their front lawn and disappear around the corner onto Patton. The killer passed within 15-feet of them. Two used car employees at Dootch Motors – Ted Callaway and Sam Guinyard – watched the gunman trot toward them as he headed down Patton toward Jefferson Boulevard. They both got a good look at him as he fled; passing just 56-feet away from them. As the killer turned west on Jefferson, four employees from Johnnie Reynolds Used Car Lot across the street looked on. Two of them – Warren Reynolds and B.M. Patterson – followed the shooter up Jefferson toward Crawford. When the gunman ducked behind a second-hand furniture store, the two men ran to the shooting scene at Tenth and Patton to notify police. [5]

Two .38 caliber hulls were found alongside the corner house at Tenth and Patton, where the killer was seen unloading his revolver as he fled, and were turned over to police. Later that afternoon a third shell was found near the corner house and given to the head of the crime lab who was on scene. A few hours later, a fourth shell was recovered in the same location. [6]

Police poured into the area of the second-hand furniture store, where the killer was last seen. Two employees at a nearby Texaco service station – Robert and Mary Brock – told police the suspect fled through the parking lot behind the station. [7]

Police soon discovered a light-gray Eisenhower-style jacket tossed under a parked car. [8]

|

FIG.3 – Oswald under arrest (James Newton MacCammon, Jr. / The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza)

The arrest

Ten minutes after the discovery of the abandoned jacket, Hardy’s Shoe Store manager Johnny C. Brewer spotted a man in shirt tails acting suspiciously in front of his store. When the man turned westward and continued up Jefferson Boulevard, away from the Tippit shooting scene, Brewer followed him. [9]

Brewer saw him duck into the Texas Theater behind the ticket-taker’s back. They called police. [10]

Thirty-five minutes after the Tippit murder, police charged into the front and back doors of the Texas Theater. [11]

When the house lights came up, Brewer saw the man he had followed from the shoe store. He was sitting near the back of the center section – third row from the back, fifth seat from the aisle. The man got up and shuffled to his right, toward the aisle, as if he was going to leave. Suddenly he stopped and sat down again, this time in the second seat as officers poured in from the lobby. [12]

Brewer alerted officers coming in the back door to the man sitting in the second seat. [13]

Police approached the man from both sides of the center section. Patrolman M.N. “Nick” McDonald was closest. He ordered the man to his feet. Without being asked, the man raised his hands and said, ‘It’s all over now.” [14]

As his hands got shoulder high, Officer McDonald reached for his waist to frisk him.

Suddenly the man took a swing and punched McDonald in the face. As the policeman reeled back, the suspect reached for his waistline and pulled a .38 caliber revolver out from under his shirt. McDonald leapt forward and managed to get his hand on the revolver’s cylinder to prevent it from rotating and the gun firing.

A flock of officers ran toward the melee and began grappling with the suspect who was finally subdued.

The subject began shouting, “Police brutality!” and “I am not resisting arrest!” [15]

He was marched out the front door of the theater where a crowd had gathered and shoved into a waiting unmarked car.

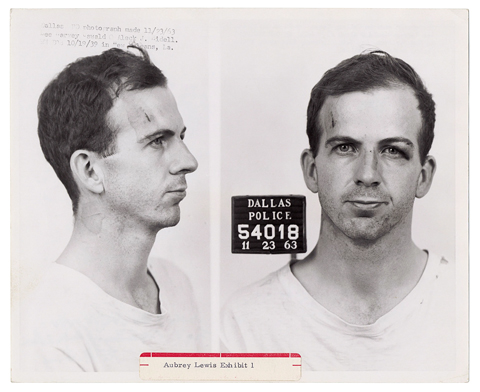

Eleven minutes later, at 2:02 p.m., arresting officers marched the suspect into the third-floor Homicide & Robbery Bureau at Dallas Police Headquarters. Several employees from the Texas School Book Depository were there giving affidavits to police regarding the presidential assassination.

They immediately identified the Tippit shooting suspect as one of their fellow employees – Lee Harvey Oswald. [16]

The evidence

Police knew right then and there that they had the prime suspect in the Kennedy assassination and the reason why Oswald killed Patrolman Tippit in the middle of the day in full-view of multiple witnesses.

Of course, gut feelings aren’t sufficient for convictions. You need evidence and the police had that in spades.

|

FIG.4 – Four of eleven witnesses. Clockwise from upper left: Helen Markham, Ted Callaway, William Scoggins, and Johnny Brewer. (Wide World Photos / Jack Beers, Dallas Morning News Collection / The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza)

Eyewitnesses

First, the police had seven eyewitnesses who either saw the Tippit shooting or saw a man fleeing the scene.

The primary shooting witness, Helen Markham, was taken to a lineup of four men at 4:35 p.m. – just three hours after witnessing the ghastliest thing anyone could imagine – the murder of a fellow human being. She positively identified Oswald as Tippit’s killer. The most convincing thing about her identification was her own visceral reaction to the moment Oswald appeared on stage in the line-up. “I had cold chills just run all over me,” she told the Warren Commission. [17] That’s a physical involuntary reaction – something that can’t be faked.

Homicide Captain J. Will Fritz, who attended the lineup, was convinced Markham’s identification was legitimate and would be enough to hold Oswald until further evidence could be developed. First, he wanted more identifications. Fritz ordered Homicide Detective James R. Leavelle, who was in charge of the Tippit case, to take Markham home and bring back more eyewitnesses to view Oswald in a lineup. [18]

Detective Leavelle returned Markham to her residence and stopped at Dootch Motors to talk with three other eyewitnesses – Ted Callaway, Sam Guinyard and Domingo Benavides. He convinced Callaway and Guinyard to come downtown to view a lineup. Benavides declined to come with them, telling Leavelle that he only saw “the officer lying in the street, but did not see the suspect.” [19]

At 6:30 p.m., a second lineup was held. Eyewitnesses Ted Callaway and Sam Guinyard both positively identified Oswald as the man they saw fleeing the Tippit shooting scene with a gun in his hand. Neither man had seen any television reports between the time of the shooting and the lineup. [20]

At 7:55 p.m., the two Davis women also viewed Oswald in a four-man lineup. They too positively identified Oswald as the man who passed within 15-feet of them as he unloaded his revolver. Neither woman had seen any television reports between the time of the shooting and the lineup. [21]

The next day, Saturday, November 23, 1963, cab driver William W. Scoggins, viewed a four-man lineup and also positively identified Oswald, though he later acknowledged he had seen Oswald’s picture on Friday. Oswald was complaining loudly during the Saturday lineup which some suggest swayed Scoggins’ opinion, but Detective Leavelle was convinced it was as good an identification as any.

“Well, Oswald was trying to complain that the other people were neater dressed than he was,” Leavelle told me. “But when Oswald started that, Scoggins said, ‘Well, he can bitch and holler all he wants too. But that’s the man I saw running from the scene.’ So, there wasn’t much problem with the identification on it.” [22]

Besides the six who positively identified Oswald as Tippit’s killer within hours of the shooting, three more witnesses – Harold Russell, B.M. Patterson, and Mary Brock – were shown photographs of Oswald in the months that followed and positively identified him as the man fleeing the scene. [23]

In 1978, yet another eyewitness, Jack Ray Tatum, told HSCA investigators that he too had witnessed the Tippit shooting and positively identified Oswald as the man he saw leaning over and talking to Tippit just before the gunfire erupted. Tatum was less than fifteen feet from Oswald as he passed the squad car and would never forget Oswald’s distinctive “smirk” – a result of Oswald habitually pursing his lips. [24]

In 2013, I interviewed the family of Firman and Doretha Dean, a couple who owned Dean’s Dairy Way, a convenience store located between the second-hand furniture stores on Jefferson Boulevard, where Oswald was thought to have temporarily sought refuge, and the Texaco service station on the corner of Crawford and Jefferson.

It turned out that the family had a secret – their mother, Doretha, was working at the store on the day of the Tippit shooting and saw Lee Harvey Oswald as he passed her store from a distance of less than ten feet. Oswald was tugging at his light-colored jacket, as if he was about to take it off, just before he ducked behind the Texaco service station. There was absolutely no doubt in her mind that the man she saw was Oswald. [25]

That’s eleven eyewitnesses who either saw Oswald shoot Tippit, or saw him fleeing the immediate area of the murder scene. Three of them – Tatum, Davis, and Dean – saw Oswald from a distance of less than fifteen feet.

That’s powerful testimony, even if you accept the fact that eyewitness testimony is the least reliable in anyone’s arsenal for conviction. Some have argued that the lineups were unfair or biased. But why would the Dallas police run a rigged lineup only to have it knocked down at trial?

Others claim that the eyewitnesses simply mistook Oswald for someone that looked like him, even producing numerous examples from FBI files in which other persons were mistaken for the real Oswald.

But eleven cases of mistaken identity? And all on the same day? Within the same general area and within minutes (and in many cases seconds) of each other? Really? Does that sound believable to anyone with an IQ above five?

Perhaps each eyewitness saw a completely different person – each one an apparition that materialized for just a few seconds, only to be replaced by a cascading series of other phantom-like figures?

The entire mistaken identity argument hinges on all of the identifications being mistaken, because if one – just one – is a true and reliable identification, then it’s game over.

Personally, I’ve always felt that Ted Callaway’s testimony was the most reliable and accurate over time. He saw Oswald pass him from a distance of less than 56-feet. Oswald even turned to face him when Callaway yelled out, “Hey man, what the hell is going on!” At the lineup, Callaway told me that he stepped back seven or eight paces so he could view the lineup from about the same distance he saw Oswald run by. That was Callaway’s idea. No one told him to do that.

“As soon as he came out – hell, I knew him,” Callaway told me. “No problem about it.” [26]

In 1964, Callaway told KRLD-TV newsman Eddie Barker, “He was the type of individual that once you see him, you never forget him.”

“Why do you say that?” Barker asked.

“There was just something outstanding about him. I guess, under the circumstances, I paid especially close attention to him especially with that gun in his hand, you know? But I had no trouble at all in picking him out of the lineup.” [27]

For nearly sixty-years we’ve be inundated with ridiculous arguments that go nowhere, especially given the fact that no one is convicted based on eyewitness testimony alone.

There must be physical evidence to support that testimony and once again, not only is there a substantial amount of physical evidence in this case, but the physical evidence collected by law enforcement leads to one simple truth – Lee Harvey Oswald murdered J.D. Tippit.

|

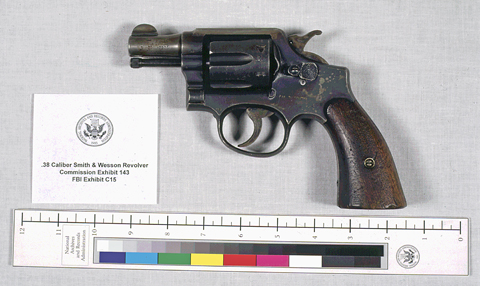

FIG.5 – Oswald’s .38 Smith & Wesson revolver. (NARA)

The weapon

First, there’s the murder weapon. The .38 caliber Smith and Wesson revolver (Serial No. V510210) pulled out of Oswald’s hand at the Texas Theater was purchased via mail-order from Seaport Traders on March 13, 1963, under the name “A.J. Hidell” – the same name on fraudulent identification cards which Oswald was carrying in his wallet at the time of his arrest.

I wrote a lengthy article on the pedigree of Oswald’s revolver back in 1998.

There can be no doubt that Oswald ordered and later took possession of the revolver he had in his hand at the Texas Theater.

As I explained in “With Malice,” Oswald’s revolver was modified to fire .38 Special cartridges prior to being sold. Because the barrel of the revolver was slightly larger in diameter than the .38 Special bullets fired through it, the bullets traveling down the barrel had a tendency to wobble, producing a confusing array of minute scratches on each slug that defied comparison. The FBI found that even consecutive bullets test-fired through the revolver could not be matched to each other. [28]

Another interesting characteristic of Oswald’s revolver was that the oversized barrel allowed propellant gases to slip between the surface of the bullet and the inside of the barrel. These gases eroded the surface of any bullets fired through its barrel.

Finally, the class characteristics of the barrel of Oswald’s revolver were found to have five lands and five grooves, with a right twist.

|

FIG.6 – One of four bullets and a brass button, recovered from Tippit’s body. (NARA)

The bullets

The four bullets recovered from Tippit’s body during the autopsy showed that they were indeed fired from a hand-gun that matched Oswald’s revolver in two key respects – the barrel of the weapon used was slightly larger than the .38 Special bullets (producing minute random scratches and propellant gas erosion on the surface of the bullets), and the class characteristics of the barrel used to fire the fatal rounds were five lands and five grooves, with a right twist.

Normally, recovered bullets can be traced to a particular firearm by comparing the unique striations imparted to the surface of a bullet when fired with bullets test-fired from a suspect weapon. The unique striations (or scratches) are like fingerprints – unique to a particular firearm to the exclusion of all others.

In the Tippit case, the bullet evidence proved to be a double-edged sword. On one hand, the random minute scratches on the surface of the bullets proved that they had been fired through an oversized barrel with the class characteristics of five lands and five grooves, with a right twist – just like Oswald’s revolver. However, the minute random scratches defied comparison with test-rounds fired through Oswald’s revolver, making it impossible for ballistic experts to say with certainty that Oswald’s revolver fired the bullets recovered in Tippit’s body to the exclusion of all other similar weapons. [29]

By the same token, the ballistic experts were unable to exclude Oswald’s revolver from among those able to produce the bullets that killed Tippit. This is a significant point often ignored by those seeking to exonerate Oswald.

|

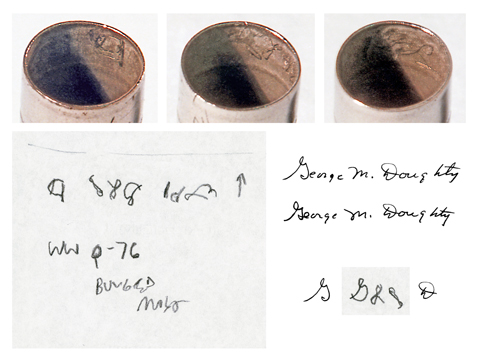

FIG.7 – Four .38 hulls recovered at the Tippit scene. (NARA)

The cartridge cases

The cartridge cases recovered at the Tippit shooting scene were another matter. Ballistic examinations quickly established that all four cartridges were fired in Oswald’s revolver to the exclusion of all other similar weapons.

This of course underscored what eleven eyewitnesses had told police – they saw Lee Harvey Oswald either shoot Tippit or flee the scene with a revolver in his hand. And that while he was fleeing, he was unloading his revolver.

Realizing that the recovered hulls destroy their case for Oswald’s innocence, detractors have worked for six decades to undermine the provenance of the cartridge cases – claiming either that the chain-of-evidence was broken, that the hulls were improperly marked (or not marked at all), or that police switched the real hulls recovered at the scene for a set fired in Oswald’s revolver.

Of course, they never back-up any of these claims with bonafide evidence. It’s always supposition, innuendo, or outright lies.

I traveled to the National Archives in 1997 in an effort to determine once and for all if there was anything to the claim that Oswald was framed with a false ballistic trail. I knew that if just one of the empty hulls was properly marked, it was game over.

While many theorists have focused on two of the empty hulls recovered by eyewitness Domingo Benavides and turned over to Patrolman Joe M. Poe, [30] few have spent any time acknowledging the chain of custody regarding the two empty hulls recovered by Barbara and Virginia Davis just a short time later.

In both cases, the empty hulls were turned over to police and marked by the officers who recovered them. I saw their marks on the inside lip of the cartridge cases housed at the National Archives with my own eyes. [31]

One of those hulls, the one recovered by Barbara Davis at about 2:00 p.m., just forty-five minutes after the Tippit shooting and only twenty-minutes after Benavides found the first two, was turned over to the head of the Crime Scene Search Section, George M. Doughty, who was on scene. He marked the shell with his initials – “GD” – in script. [32]

|

FIG.8 – Top: George M. Doughty’s initials in the .38 hull (Q-76) recovered by Barbara Davis. Bottom left: Notes taken at NARA regarding Doughty’s initials. Bottom right: Comparison of Doughty’s signature with initials in shell. (© 1997 Dale K. Myers. All Rights Reserved.)

I photographed those marks and published them in “With Malice” for the whole world to see. Game over, right? Not if you’re bent on exonerating Oswald at all costs. No matter what the argument, it’s never enough for these deniers.

On various Internet forums you’ll read how the chain of custody doesn’t hold up, that Barbara Davis never marked the shell herself (was she supposed to?) and that the shell shown her only looked like the one she recovered, and that she didn’t even sign the FBI report (was she supposed to?) dealing with the chain of custody surrounding the shell she recovered.

For these reasons, self-proclaimed Internet legal buffs, who got their schooling watching TV’s “Law and Order,” argue that none of this evidence would be allowed at trial.

First of all, I’m pretty sure that it’s up to a judge to decide whether evidence can be introduced at trial. It’s not the sole purview of defense attorneys. And you can bet the prosecution will have something to say about attempts to exclude evidence at trial.

Second, there’s never going to be a trial. Jack Ruby robbed us of that. But even if there was a trial, does anyone really think that Dallas Police Crime Lab Captain George M. Doughty, a 22-year veteran of the police force at the time, would not have been called to testify about his activities at the Tippit crime scene, including the fact that he took into evidence an empty .38 caliber hull given him by eyewitness Barbara Davis, that he marked the shell with his initials, and that he could identify his mark in court?

And even if you insist that the ballistic evidence would be excluded at trial and Doughty would be barred from testifying, what are we really arguing about here? Whether Oswald would be acquitted at trial or whether Oswald shot Tippit?

The forensic evidence is unequivocal – Oswald was arrested with the Tippit murder weapon in his hand thirty-five minutes after the shooting.

But there’s even more damning evidence.

|

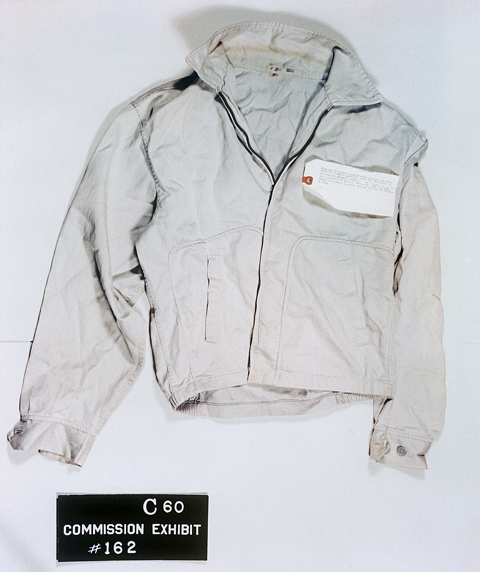

FIG.9 – The light-gray jacket recovered from the Texaco service station parking lot. (NARA)

The jacket

Ten minutes after shooting Tippit, police discovered that the killer tossed his light-gray Eisenhower-style jacket under a car in the parking lot of the Texaco service station, two blocks from the murder scene, in what many believe was an obvious effort to disguise his appearance.

One witness who saw a portion of Oswald’s flight, Doretha Dean, the convenience store owner, saw Oswald from a distance of ten feet tugging at his jacket as if to remove it just before he ducked behind the Texaco service station where the jacket was found six minutes later.

By Marina Oswald’s account, her husband only owned two jackets – a dark-blue one and a light-gray one. [33]

|

FIG.10 – Oswald’s dark-blue jacket found in the first-floor lunchroom of the TSBD. (NARA)

The dark-blue jacket was discovered in the first-floor lunch room of the Texas School Book Depository in mid-December, 1963. [34]

The light-gray jacket was retrieved by Oswald from his rented room on North Beckley Avenue around 1:00 p.m., according to his housekeeper Earlene Roberts. [35]

Mrs. Roberts told a radio audience during an interview broadcast on KLIF radio at 5:00 p.m. – just three hours and forty-five minutes after the Tippit murder – that she saw Oswald hurry into his room and emerge zipping up “a light-gray coat” as he headed back out the door. [36]

When Oswald was spotted outside Hardy’s Shoe Store by manager Johnny C. Brewer, twenty-two minutes after the Tippit shooting, and a little more than a half-hour after Roberts saw Oswald donning his light-gray coat, Oswald was in shirt-sleeves. [37]

This of course begs the question – What happened to Oswald’s light-gray jacket?

The obvious answer, based on eyewitness testimony alone, is that he dumped it in the Texaco service station parking lot after he gunned down Tippit.

But, of course, the handful of deniers seeking to absolve Oswald from guilt refuse to acknowledge this obvious conundrum.

But that’s not the most shameful episode in the light-gray jacket saga.

In 1997, during a research trip to the National Archives, I discovered something that the earliest deniers had known and had been hiding for thirty-five years.

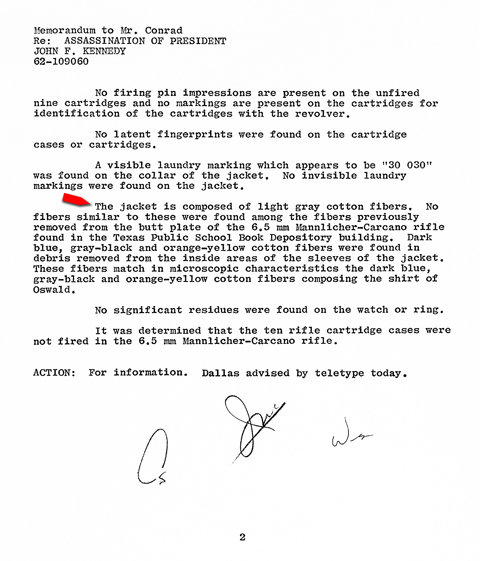

While fellow researcher Todd W. Vaughan and I were combing through some of the earliest Warren Commission documents, I ran across the results of an FBI lab examination of the light-gray jacket.

According to the report, FBI lab technicians reported that “dark blue, gray-black and orange-yellow cotton fibers were found in debris removed from the inside areas of the sleeves of the jacket [discarded behind the Texaco service station]. These fibers match in microscopic characteristics the dark blue, gray-black and orange-yellow cotton fibers composing the [brown arrest] shirt of Oswald.” [38]

|

FIG.11 – FBI report describing results (red arrow) of the lab examination of the light-gray jacket. (NARA)

Are you kidding me? I looked over at Todd, “Come and take a look at this.”

The lab report was part of Robert P. Gemberling’s 800-page-plus collection, dated December 10, 1963, and listed by the Warren Commission as CD7.

The numerous FBI reports contained in CD7 covered assassination eyewitnesses, interviews with Oswald’s relatives, Oswald’s background, the tracing of weapons connected with Oswald, crime scene and related searches and FBI lab results, other investigations related to Oswald and Ruby, and much more – and all of it well-known and referenced by first-generation authors like Harold Weisberg, Mark Lane, Penn Jones, and others.

All except, of course, this damnable FBI lab report which clearly showed that the light-gray jacket recovered by police from the Texaco service station parking lot had been worn by someone who was wearing the exact same shirt, or at the very least, one identical to the shirt that Lee Harvey Oswald was wearing when he was arrested.

|

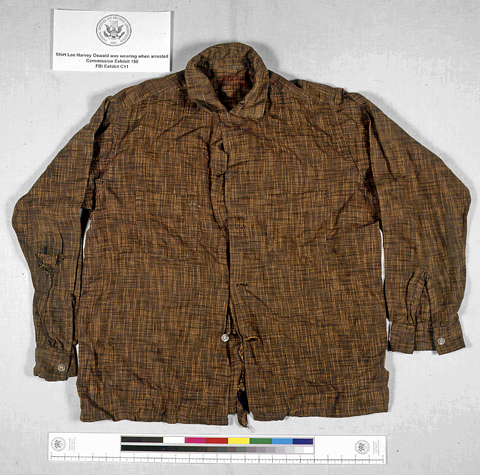

FIG.12 – Fibers found in the light-gray jacket matched the microscopic characteristics of this shirt, the one Oswald was wearing when he was arrest. (NARA)

This fiber link, unreported by numerous first-generation researchers, who undoubtedly discovered it long before I did and hid the discovery for nearly thirty-five years, provides the strongest evidence yet that the light-gray zipper jacket dumped on the Texaco station parking lot had been worn by Lee Harvey Oswald on the day of the Tippit killing.

Putting it all together

The sum total of all of the evidence points a clear and unwavering finger at Lee Harvey Oswald.

Eleven eyewitnesses placed Lee Oswald at the scene; not some unknown individual who resembled Lee Oswald. Either Oswald was correctly identified by eleven eyewitnesses or they were all mistaken. Which do you think it was?

The firearm that Oswald had in his hand when he was arrested was purchased and possessed by him. That same firearm was ballistically established as being the firearm that produced the .38 caliber empty hulls recovered at the Tippit murder scene. The bullets recovered from Tippit’s body were ballistically established as having been fired from either Oswald’s revolver or one with the same class characteristics and same oversized barrel. Which do you think it was?

The jacket found behind the Texaco service station was worn by Lee Harvey Oswald on the day of the assassination, or by someone wearing a shirt composed of the exact same dark blue, gray-black and orange-yellow cotton fibers as the one Oswald was wearing that day. Which do you think it was?

And that’s just the physical evidence and the eyewitness accounts. On top of all that are the circumstances surrounding the evidence.

Lee Oswald left the Texas Book Depository within three-minutes of the presidential assassination. He caught a bus that got hung up in traffic, secured a bus transfer pass, and walked south to the Greyhound Bus Station where he hailed a cab – an unprecedented act in and of itself, given his frugal habits – which took him to the area near his Oak Cliff room.

Any law enforcement officer will tell you that these are the actions of someone in flight.

With an hour, Dallas police discovered the sixth-floor sniper’s nest and a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle that Lee Oswald purchased in early 1963 and brought to the Depository that morning. The rifle would later prove to be the Kennedy murder weapon.

Oswald instructed the cab driver to drop him five blocks south of his residence – another clear sign of deception. He hurried back to his rented room and within a few minutes left the residence zipping up “a short gray coat.” Police suspect he had also armed himself with the .38 caliber Smith & Wesson revolver he had purchased at the same time he bought the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle.

At about 1:15 p.m., Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit stopped to question Oswald as he walked down Tenth Street. When Tippit emerged from his squad car, Oswald shot him four times and fled the scene.

Ninety-seconds later, Oswald attempted to break-in and hide in one of two second-hand furniture stores on Jefferson Boulevard, just east of Crawford. When that failed, he continued west, took off his “short gray coat” and tossed it under a car parked behind the Texaco service station at Jefferson and Crawford. He was last seen heading west down the alley between Tenth and Jefferson.

Sixteen minutes later, Oswald was spotted in front of Hardy’s Shoe Store on Jefferson Boulevard, four-and-a-half blocks west of the Texaco service station. His hair was disheveled and he was in shirt-sleeves, tails out.

When he continued westward, the shoe store manager followed him and saw him duck into the Texas Theater. Police were called.

Thirty-one minutes after the Tippit shooting, the police dispatcher informed investigating officers that they had a report that a suspect “just went into the Texas Theater.”

At 1:47 p.m., officers descended on the theater and as they approached Oswald he declared, “It’s all over now,” pulled the hand-gun used to murder Tippit, and attempted to shoot the arresting officer. He was quickly subdued and taken to police headquarters where police discovered he was an employee of the Texas School Book Depository.

Just thirty-six minutes elapsed between the time Patrolman Tippit was shot and police pounced on Oswald at the Texas Theater.

Nearly all of this narrative was broadcast on television and radio within hours of the actual events; much of it as it was unfolding in real-time. Detailed newspaper accounts followed in subsequent days.

Given the circumstances, the eyewitness testimony, and the physical evidence, it’s really hard to believe that anyone could conclude that Oswald had nothing to do with Tippit’s death.

|

FIG.13 – Oswald’s mugshot. (Aubrey Lewis Exhibit 1 / NARA)

A perverted sense of justice

It’s one thing to dig deep on the details of a murder case to make sure that an innocent citizen isn’t caught up in something not of his making. But here is a murder case that has been raked over the coals so many times and so many ways that you just know in your gut that if Oswald were innocent, the evidence for his innocence would have been laid bare long ago.

I’m talking about real evidence, not subtle nuances or a re-interpretation of existing evidence, but genuine new evidence that counters what police gathered and journalists reported on November 22, 1963.

And yet, here we are, nearly sixty-years later, having to put up with the loud, boisterous ramblings of people who actually believe that Lee Oswald was framed – that’s right, framed – for a crime he didn’t commit. Seriously?

Have these people even read the historic record? No, of course not. They’re too busy writing page after page of Internet rubbish as they twist and distort the truth to fit some half-assed narrative that they think is convincing proof that veteran law enforcement officers, the ones who actually handled the case, got it all wrong, or worse, conspired to frame a hapless Oswald.

Here’s the ultimate litmus test for any of their theories – Have these purveyors of foolishness ever named those Dallas police officers who conspired to frame Oswald before they were dead in the grave, unable to defend their good name? Answer: Never.

Here’s a better question: How exactly did these police conspirators frame Oswald? And be specific – time, dates, names – the entire mechanics of how it all went down. And since these Internet bumpkins are big on only allowing evidence and testimony that would stand up in court, lets see all the signed affidavits and tape-recorded confessions from all the police whistle-blowers who support their cockamamie theories. Are we ever going to see any of this? Answer: Never.

I could name-names and go through all of their crazy claims, line-by-line, and expose them for the frauds that they are, but what’s the point? And you know exactly who I’m talking about. I’ve been battling these icons of idiocy for far too long. It always ends up the same – they’re wrong; their hollow arguments over-whelmed again and again by pillars of fact.

There’s something about the Kennedy assassination that attracts some of the craziest people. Perhaps it’s the so-called “mystery” surrounding the event. Anyone who has spent any critical amount of time with this subject knows that this is largely poppycock. But it’s the notion that the assassination is “unsolved” that draws people in.

Eventually, some of the amateur Sherlocks get to the Tippit shooting – the most maligned and misunderstood aspect of the whole weekend. I think they see it as easy pickings for their off-the-wall analyses. And trust me, much of it is truly out there.

The most dangerous propagators of stupidity are the ones who fancy themselves as defenders of the innocent. In Oswald, they see an innocent lamb who needs defending from so-called Warren Commission bullies, bent on damning Oswald to historic hell.

But no one is anxious to pin a murder on an innocent man, least of all Oswald. The simple fact is, the evidence for and against Oswald has been weighed over and over again and the evidence shows a preponderance of guilt. And not just by a reasonable doubt, but beyond all doubt.

Let’s face it, these self-proclaimed defenders aren’t offering justice at all. They’re bent on substituting distorted, and often irrational and illogical narratives, for truth. In their mind this perverted sense of justice over-turns facts, common sense, and the long-established historic narrative that collectively point an accusing finger at Oswald. And for what? Who does their brand of justice really serve?

In the opening lines of “With Malice,” I wrote:

Lee Harvey Oswald murdered Officer J. D. Tippit. The Dallas cops believed it. The newspapers reported it. The Warren Commission made it official and the House Select Committee on Assassinations reaffirmed it. Why then, do so few accept that verdict? [39]

Yes, indeed. Nearly sixty-years on, that’s the question. Why do so few accept that verdict?

|

FIG.14 – Pallbearers carry J.D. Tippit’s casket to a waiting hearse. (DMN)

Grief too much to bear

When J.D. Tippit’s sister, Chris, telephoned her husband on November 22, 1963, he was at work.

Jack Christopher told me that when he got to the phone, he could hardly understand his wife through her tears. All he could make out was that the person he had known since he was sixteen, J.D. Tippit, had been killed and for him to come home at once.

He said he started off, driving as quick as he could, but when it sank in what had happened, he pulled over and wept like a school boy. It was a grief too much to bear.

I think about Jack on the anniversary of the Tippit murder. I think about the entire Tippit family, their friends, and all of the people that were touched by the sudden and violent death of one so-loved. I’ve met them. I know them. My heart breaks for them.

In the end it doesn’t matter one whiff what a handful of self-promoting Internet trolls have to say about people they never met, don’t know, and wouldn’t be welcomed at the back door. Nor should what they have to say about this case matter to you.

What cuts close to the bone on a day like today is the human toll.

“Chris and I then went to see J.D. at the funeral home,” Jack told me in 1999, his voice growing quiet, his demeanor reflective. He was back there, in 1963. I could see it in his eyes. He was reliving the moment. He looked up at me.

“They had already had that autopsy and had him in Dudley M. Hughes funeral home for viewing that very night.” He stopped. He could hardly believe his own words. If he hadn’t lived it, he probably wouldn’t believe it himself.

“And, of course…” he continued. He stopped again.

“No,” he managed to say, “I don’t guess you could imagine what it was like to see your best friend laying up there. It was just like a nightmare. His life gone” – Jack snapped his fingers – “just like that.” [40]

That’s what I think about on a day like today.

Just a small part of the human suffering that Lee Harvey Oswald left in the wake of his senseless and selfish act. [END]

Footnotes

1. DPT/C-1, 1:17:41 p.m.

2. “Wild-Driving Gunmen Wound Two Policemen,” Dallas Morning News, Tuesday, January 23, 1951, Part-1, p.1; “Policeman Johnny Sides Turns in Badge for Keeps,” Dallas Morning News, Thursday, February 8, 1951, Part-1, p.1 [Note: Undercover Dallas police detective Leonard C. Mullenax, 29, was shot in the hallway of the Sherman Hotel during a scuffle on February 10, 1962 – nearly two-years (21 mos.) before Tippit was gunned down.]

3. Rutledge, John, “Dallas Police Officer Shot, Killed by Bandit,” Dallas Morning News, Monday, November 13, 1967, Section 1, p.1 [Two Dallas police officers were killed in high speed chases in the wake of the Tippit shooting – Francis W. Bennett on September 5, 1964, and James D. Stewart on November 12, 1967.]

4. Interview of W.R. Westbrook, June 21, 1986, pp.2-3, Larry Sneed Collection

5. Myers, Dale K., “With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit,” (2013, Oak Cliff Press, Inc., Milford, MI), pp.109-142

6. Ibid., pp.126-127, 318-320, 422

7. Ibid., pp.142, 157-160

8. Ibid., pp.175-177

9. Ibid., pp.197-198

10. Ibid., pp.198-201, 214-216

11. Ibid., pp.223-228

12. Ibid., p.229

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid., pp.230-231

15. Ibid., pp.232-240

16. Ibid., pp.241-244, 256

17. 3H311, WCT Helen Markham

18. 4H221, WCT John Will Fritz

19. Supplementary Offense Report, November 22, 1963, James R. Leavelle, C.N. Dhority, p.1; Report on Officer’s Duties in Regards to Officer Tippit’s Murder, Undated, J.R. Leavelle, Badge No.736 – DMARC

20. Myers, op. cit., pp.282-283

21. Ibid., p.287

22. Author’s interview of James R. Leavelle, July 1, 1996, p.4

23. Russell Exhibit A; Patterson (B.M.) Exhibit A; Brock (Mary) Exhibit A

24. HSCA RIF 180-10087-10355, Interview of Jack R. Tatum, February 1, 1978; Author’s interview of Jack Ray Tatum, March 3, 1983, p.12; Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.2

25. Myers, Dale K., “Warren Reynolds and Oswald’s Jacket: New Evidence Surrounding Oswald’s Escape from the Tippit Murder Scene,” November 22, 2020 – http://jfkfiles.blogspot.com/2020/11/warren-reynolds-and-oswalds-jacket.html

26. Author’s interview of Ted Callaway, December 2, 1986, p.12

27. “November 22, 1963: The Warren Report,” CBS Television, Broadcast: September 27, 1964, Transcript, pp.9-10 – Dale K. Myers Collection

28. CD774, p.2

29. Myers, op. cit., pp.312-314 [Note: One ballistic expert, Joseph D. Nicol, did find sufficient individual characteristics on one of the four bullets to conclude that it was fired in Oswald’s revolver to the exclusion of all other weapons. However, none of the other eight ballistic experts agreed.]

30. Patrolman Poe initially told the Warren Commission that he couldn’t swear that he marked the two shells given him by Benavides and which he subsequently turned over to George M. Doughty, head of the Crime Scene Search Section, who was at the Tippit shooting scene. Poe later told the FBI that he couldn’t find his mark, the initials J.M.P., on any of the shells. (See: “With Malice, 2013, pp.323-327)

31. National Archives II Trip, December 5, 1997

32. Myers, op. cit., pp.328-329

33. NARA 1993.06.03.10.40.43.12000, p.502 (Interview of Marina Oswald, dated April 3, 1964); CD206, p.188

34. CD205, p.209

35. Myers, op. cit., pp.98, 103

36. KLIF 1190-AM, November 22, 1963, 5:00 p.m., Transcript, pp.1-4 – Dale K. Myers Collection

37. 7H3 WCT of Johnny Calvin Brewer

38. FBI RIF 124-10009-10499, FBI Memo, Jevons to Conrad, December 3, 1963, p.2 [Note: The original FBI lab notes and report referenced by the CD7 memo, and additional reports and teletypes referencing the fiber evidence have since been located.]

39. Myers, op. cit., p.23

40. Videotaped interview of Robert Jack Christopher, November 12, 1999 – Dale K. Myers Collection