John Armstrong's fantasy cabal behind the killing in Oak Cliff

|

Reserve Sgt. Kenneth H. Croy (left) and Capt. W.R. Westbrook (right).(Graphic: © 2020 DKM)

By DALE K. MYERS

A member of the so-called JFK research community once proclaimed, “If we get too bogged down in the details, we’ll wind up proving Oswald killed Kennedy.” Ah, those pesky details.

The same could be said for the murder of Dallas patrolman J.D. Tippit, gunned down on an Oak Cliff side-street forty-five minutes after the president’s murder.

Conspiracy theorists and the Dallas “research community” have been very busy avoiding those pesky details in their fifty-seven-year quest to exonerate Lee Harvey Oswald for the killing of the 39-year-old police officer – a case that was so open-and-shut that it’s hard to believe that we’re here more than five decades later pretending that we don’t know anything about Tippit’s murder.

The most recent explanation for the events on Tenth Street, offered by persons dedicated to Oswald’s exoneration, is the claim that two members of the Dallas Police Department lured Tippit into a broad daylight ambush to keep him from ruining their plans to frame Oswald for the Kennedy assassination.

Here is their theory in a nutshell: Conspiring with the CIA, W.R. Westbrook, Captain of the Dallas Police Personnel Department, and Kenneth H. Croy, a Dallas Police reserve sergeant, met on Tenth Street, murdered Tippit in a pre-arranged plot, then covered-up their involvement and framed Oswald for the killing.

So says the chief architect of this fantasy, John Armstrong, author of Harvey and Lee (a preposterous fairy-tale about two Oswalds groomed by the intelligence apparatus to kill Kennedy), with generous assistance from Bill M. Simpich and others who have lent their voices to this poppy-cock for the better part of six years.

The claim is not backed by one scintilla of substantiated evidence, but when has that ever mattered to the exonerators? Ah yes, those pesky details.

I have been watching this nonsense from the sidelines, shaking my head, and wondering how on Earth anyone could take this seriously?

Like most claims that drift so far off the path of common sense, Armstrong & Company have laced enough “ifs” and “maybes” into their narrative that it probably sounds almost plausible to neophytes of the Tippit story.

Eventually, I suppose people with both feet on the ground and a brain in their head will figure out that the Armstrong & Company’s narrative is bogus from top to bottom.

But having never been accused of being one willing to sit on the sidelines until that happens, allow me to nudge those still pondering Armstrong’s claims toward reality with a heavy dose of those pesky details.

You will soon see that not only have Armstrong & Company bamboozled the public with an avalanche of innuendo and falsehoods about two dedicated public servants, but they’ve also twisted eyewitness accounts into a multitude of lies in a determined effort to paint Lee Harvey Oswald – a self-admitted Marxist, and accused murderer – as an innocent patriot. Gee, what a surprise.

The false claims made by Armstrong & Company are too numerous and convoluted to be addressed coherently in a single blog article. Given that life is short and I don’t wish to waste your time or mine, I’ll focus on Armstrong’s main claims relating to the Tippit murder and the truth of the matter. Strap in, here we go.

W.R. Westbrook

Captain William Ralph “Pinky” Westbrook was born in Benton, Arkansas, in 1917. He was a farm boy. He graduated from Benton High School and went to California. He came back to Dallas in October, 1937, and joined the Dallas Police Department in 1941. He served as a radio patrolman for 4 years (1941-45), was promoted to sergeant, which he served as for 7 years (1945-52), and made captain in 1952. [1]

In 1963, Westbrook was in charge of the Personnel Bureau (what most police departments would later call ‘Internal Affairs’), and was in his office when he learned of the assassination. After directing other officers in his department to the shooting scene, Westbrook himself made his way to Elm and Houston. [2]

Westbrook told the Warren Commission, “There wasn’t a car available, and so I walked from the city hall to the Depository Building.” [3]

Armstrong finds Westbrook’s claim that he walked solo to the Depository to be highly-suspicious, and although this is a minor point in the scheme of things, it is worth noting what Armstrong claims next, in order to paint Westbrook as a liar.

Armstrong writes: “Westbrook told the W.C., ‘After WE reached the building [notice that Westbrook said WE, PLURAL, yet told the WC he walked by himself to the Book Depository], I contacted my sergeant, Sgt. Stringer…’ (all emphasis and notes added by Armstrong)” [4]

STOP! That’s not what Westbrook said at all. Here’s the actual quote from the testimony:

WESTBROOK: Do you want me to continue?MR. BALL: Go right ahead, sir.WESTBROOK: After we reached the building, or after I reached the building, I contacted my sergeant, Sgt. R.D. Stringer… (emphasis added) [5]

As you can see, Armstrong deleted – without explanation or ellipses (which is common when omitting information) – Westbrook’s self-correction, effectively changing the testimony in order to make the suggestion that Westbrook was accompanied by some unknown individual (oooh, a conspirator!) during his walk to the Depository, and thus, Armstrong implies Westbrook was withholding information from the Commission.

Really? It appears clear that the only individual withholding the truth about this episode is Armstrong. There are many more examples of this kind of subterfuge throughout Armstrong’s writings, but if we stop to acknowledge each one, this article will grow exponentially, and I propose that shorter is better. Let’s move on.

Armstrong’s big beef with Westbrook is that, as Armstrong claims, Westbrook’s “whereabouts from the time he was last seen at the police station (circa 12:35 p.m.) to his arrival at the book depository (around 1:16 p.m.) are unknown” and that Westbrook’s account gave him “an alibi to account for 40-50 minutes of his time” on November 22, 1963. [6]

Armstrong will later charge that Westbrook was up to no good during those 50-minutes, but before we get to that, let’s examine this first claim.

What evidence does Armstrong offer to discount Westbrook’s testimony to the Warren Commission that he walked to Dealey Plaza from city hall?

Armstrong claims: “…Westbrook told the W.C. that he heard the police dispatcher report ‘over his radio’ that a police officer had been shot in Oak Cliff. ‘His radio’ is a clear indication that Westbrook drove and parked his unmarked police car to the TSBD.” [7]

Really? That’s it!? No films or photographs or affidavits to show that Westbrook was elsewhere at the prescribed time. Nada. Instead, we get the weakest of claims that the errant phrase “my radio” carries meaning so diabolical that it turns the entire Tippit case on its head.

In the end, Armstrong finally coughs up the only real evidence he has to discredit Westbrook’s testimony about how he arrived at the Depository – his own personal opinion that Westbrook’s story is “a total lie”. [8] That’s rich.

Sgt. Henry H. Stringer told me in 1983 that Captain Westbrook rode with him from city hall to the depository along with two other officers – Frank M. Rose, Burglary and Theft Bureau (driving) and Joe Fields, a detective in the Personnel Bureau. They split up upon arrival and helped searched the TSBD (films support Stringer’s recollection), then got back together just before the call came over the radio about the Tippit shooting. [9]

Of course, Stringer’s twenty-year-old recollection isn’t as strong as Westbrook’s sworn 1964 testimony, but who knows? More important, in the big scheme of things, what does it matter?

Armstrong also claims that Westbrook lied about what he did at the Depository when he arrived.

Westbrook testified that he contacted his Sergeant, R.D. Stringer, [10] who was standing in front of the building and that he then “went inside the building to help start the search and I was on the first floor and I had walked down an aisle and opened a door onto an outside loading dock, and when I came out on this dock, one of men hollered and said there had been an officer killed in Oak Cliff.” [11]

Armstrong finds this suspicious for no other reason than Westbrook said he went inside to help “start the search” which, Armstrong points out, had been going on for at least “a half hour” by the time Westbrook arrived. Apparently, Armstrong believes this is all a great big lie and that Westbrook isn’t even at the Depository helping out with the search. To call Armstrong’s reasoning – and supporting evidence – imbecilic would be kind. [12]

Before we get to what that no-good-so-and-so Westbrook was up to during those suspicious 50-minutes (according to Armstrong), we have another “liar” to introduce.

Kenneth H. Croy

Sergeant Kenneth Hudson Croy was born in Dallas, Texas, in 1937. By the time of the assassination, the 26-year-old was in the real estate business, the steel erection business, and owned a Mobil service station. He had been a professional rodeo cowboy since he was fifteen-years-old and in August, 1959, he became a reserve Dallas police officer. By 1963, he held the rank of sergeant. [13]

On November 22, 1963, according to Armstrong’s crystal ball, Sergeant Kenneth Croy was busy plotting with Captain Westbrook to frame Oswald for the Kennedy assassination!

But first, Croy was assigned to crowd control in the 1800 or 1900 block of Main Street. After the motorcade passed his position, he walked back to city hall where his car was parked. [14]

Armstrong tells us that Croy was “sitting in his car at City Hall – the same location as Capt. Westbrook” (emphasis by Armstrong) when President Kennedy was shot. [15] Uh-oh!

Truth be told, Croy wasn’t as sure of where he was when Kennedy was shot as Armstrong claims. Here’s the relevant testimony:

MR. GRIFFIN: Where were you at the time President Kennedy was shot?CROY: Sitting in my car at the city hall. I would guess, I don’t know.MR. GRIFFIN: Is that where you were located when you heard he was shot?CROY: No. I was on Main Street trying to go home.MR. GRIFFIN You were driving your car down Main Street?CROY: Yes.MR. GRIFFIN: About where were you on Main Street?CROY: Griffin. [16]

Main at Griffin is normally a four-minute drive from City Hall. Sergeant Croy described being “hemmed in from both sides” [17] when he heard that the president had been shot, so it may have taken him longer to reach Griffin than normal.

Sergeant Croy’s car was equipped with a police radio that allowed him to monitor chatter on Channel One, however, it didn’t allow him to transmit. This was normal for reserve units. Consequently, Croy would have heard of the shooting in Dealey Plaza over the police radio at about 12:40 p.m. [18]

In any case, it wouldn’t make any difference whether Croy was sitting in his car at City Hall at 12:30 p.m., when Kennedy was shot, since Armstrong acknowledges that Westbrook was one of the last to leave his office after learning the news. Surely, by then, Croy was stuck in traffic on Main Street.

No problem, anything goes when the facts don’t matter. But wait, there’s more!

According to Croy’s testimony, it took him “at least 20 minutes” to drive five blocks to the Dallas Court House at Main and Houston. [19] Croy asked the officers standing in front if they needed assistance? They said, ‘No’, and just then, Croy’s wife pulled alongside him. He asked her if she wanted to get something to eat. She replied, ‘Yes’, and they agreed to meet at Austin’s Bar-B-Que in Oak Cliff for lunch. [20]

Croy planned to drive to his parents’ home at 1918 Old Orchard Drive, just off West Colorado Blvd. near Hampton, change clothes, and meet his wife at Austin’s at Hampton and Illinois. [21]

Armstrong finds all of this highly suspicious. Why? Because, Sergeant Croy was separated from his wife at the time! Armstrong writes:

“Croy would have us believe that after shots were fired at the President, he left the police station and was told by unknown officers that his services were not needed, when many off-duty police officers were called at home and told to report for duty. Croy testified that while talking with the police officers in front of the courthouse his estranged wife ‘pulled up beside me’ in her car. They began talking and then decided to go to lunch together at Austin’s Barbecue, even though Croy and his wife were separated. But first, Croy said that he needed to change clothes at his parents’ home. On the day of President Kennedy’s assassination, Croy would like us to believe that his priorities were to drive to his parents’ house, change clothes, and have lunch with his estranged wife!!” [22]

For Armstrong, this is all too much to bear. What he leaves out is telling.

Kenneth Croy and his wife, Betty, were married when he was 17 and she was just 15-years-old. By the time of the assassination, they had two children – ages 7 and 6. Their separation lasted just two weeks, during which time, Croy lived at his parents’ home. The couple moved back in together within 14 days and had two more children before they separated for good in 1975. [23]

Clearly, they were on speaking terms during their brief separation and given the fact that officers told Sergeant Croy that his assistance wasn’t needed at the assassination scene, it doesn’t seem unusual that Croy would opt for a lunch with his estranged wife.

Armstrong & Company, on the other hand, find something far more sinister afoot here. In their minds, Sergeant Croy wasn’t planning to have lunch with his wife. Oh no! He was planning to be an active participant in the murder of a fellow police officer and then become an accessory after the fact in the assassination of the President of the United States!

Oh, yes! And what evidence does Armstrong offer to support this outrageous allegation? Armstrong simply doesn’t believe Kenneth Croy’s explanation. That’s it. Nothing else.

But, why doesn’t Armstrong believe Croy? Armstrong’s suspicions apparently arise from the vacuum left if we simply ignore Croy’s Warren Commission testimony.

That’s right, folks. Armstrong assures us that “Croy’s Warren Commission testimony aside, his whereabouts from 12:30 p.m. to 1:10 p.m. are unknown.” [24]

Uh??? Yes, you read that right. (Read it again.) For Armstrong, if you abandoned Croy’s testimony (along with reason and logic apparently), anything is possible! (Seriously. You can’t make this up.)

In this case, abandoning Croy’s testimony allows Armstrong to claim that Croy’s testimony was concocted to cover-up his activities that afternoon with Captain Westbrook – namely (as Armstrong will ultimately charge), to stake out Oswald’s rooming house, to help Westbrook murder Officer J.D. Tippit, and ensure the framing of Oswald following his arrest at the Texas Theater.

Westbrook and Croy

Once Westbrook and Croy are stripped of their sworn testimony, Armstrong fills the void with his own paranoid fable of conspiracy and murder – not one syllable traceable to anything that any reasonable person would consider as evidence.

How crazy does Armstrong’s fantasy get?

Armstrong writes that Officer Tippit knew one of the dual-Oswalds (Armstrong’s Harvey and Lee), and either knew about, or knew personally, the other one (Armstrong himself hasn’t made up his mind which fantasy is true).

Armstrong speculates that “Tippit’s assignment on November 22 was to make sure that both young men arrived at the Texas Theater” and that Tippit was sitting in his squad car at the Gloco Service station, located on the south end of the Houston Street viaduct, waiting for Cecil McWatter’s bus to drop off one of the dual-Oswalds. This particular “Oswald” was told to look for the squad car (Tippit’s) which would drive him to the Texas Theater. [25]

But something went horribly wrong, according to Armstrong. “Oswald” did not get off the bus in front of the Gloco station as planned (he had bailed out of the bus downtown and was heading to his room via William Whaley’s taxi cab). Yikes!

According to Armstrong, Tippit followed the bus south on Marsalis to Jefferson and when “Oswald” failed to emerge anywhere along that route “Tippit knew there was a problem.” [26] So, of course, he rushed to the Top Ten Record Shop to make a phone call, presumably to his CIA handler.

On planet Armstrong, Captain Westbrook knew all of this – that “Oswald” was supposed to be riding on McWatter’s bus and that Tippit was waiting for Oswald to arrive via bus at the Gloco service station.

Let’s stop for a moment. Ladies and gentlemen, this is all so much horse-shit that it is hard to even acknowledge that someone would put this in writing and attach their name to it. Why did I include it? Because sometimes you have to experience an “acid-trip” to appreciate just how crazy people are that are willingly to drop it.

Needless to say (but I will anyway), not one single word of Armstrong’s scenario has any basis in fact.

Back to the conspirators in blue

With that bit of background under our belts, let’s return to those evil-doers, Captain Westbrook and reserve Sergeant Croy, as they attempt to control the big conspiracy unfolding on November 22, 1963.

After learning of the attempted assassination of President Kennedy (at this time, no one outside of a handful at Parkland Hospital knows he is dead), Armstrong imagines Westbrook and Croy driving from City Hall to Dealey Plaza in Westbrook’s unmarked dark blue police car, [27] arriving at about 12:40 p.m. (Remember, Armstrong rejects Westbrook’s testimony that he walked the distance solo.)

Numerous still photographs and news films were shot on scene during this period, but apparently both Westbrook and Croy escaped detection.

Next, Armstrong fantasizes that Westbrook and Croy boarded Cecil J. McWatter’s bus looking for Oswald who had just departed with a bus transfer in hand. This allegation is based solely on the statement of 17-year-old Roy Milton Jones, a passenger on board McWatter’s bus who claimed that shortly after an individual he thought might have been Oswald left the bus, “two police officers boarded the bus and checked each passenger to see if they were carrying firearms.” [28]

Armstrong implies that the two officers are Westbrook and Croy although he doesn’t explain how the “two officers” Jones described transformed into one plainclothesman (Westbrook) and one uniformed officer (Croy). One would think that a citizen describing “two officers” would be referring to two, clearly identifiable, uniformed officers.

In order to conflate Jones’ report with a bit of old-fashioned cover-up, Armstrong assures us that “the presence of two police officers boarding McWatters’ bus was not reported to the Warren Commission nor investigated by the FBI or Dallas Police,” apparently allowing Westbrook and Croy’s nefarious activities to escape detection.

Yet, there is an FBI report, ordered by the Warren Commission, laying in the files of the Commission at the National Archives with a Commission Document number (733) attached to it, for all to see. Some cover-up, uh?

Alleged cover-up aside, Armstrong leaves out one key fact about Roy Milton Jones’ statement – one that eliminates Westbrook and Croy (even if you wanted to believe Armstrong’s nonsense) as the “two officers” described.

Jones told the FBI that the “bus was held up by the [two] police officers for about one hour…” [29]

Obviously, the “two officers” shaking down the McWatter’s bus shortly after 12:43 p.m. can’t be Westbrook and Croy since, according to Armstrong’s own fairy tale, the two co-conspirators were off on their next task which took them to Oswald’s rooming house at 1:00 p.m. (Ahhhh, those pesky details.)

Stake out in Car No.207

Never mind reality. Armstrong’s “Captain Westbrook” was wondering why “Oswald” had abandoned the plan and left the Marsalis bus?

A quick aside: Have you ever noticed how easy it is for conspiracy theorists to read the minds of people in the past and know exactly what they’re thinking and what motivates them? It must be a gift. (Personally, I would be satisfied to know why my neighbor insists on mowing his lawn every evening when I’m trying to relax and eat dinner. Perhaps the clairvoyant Armstrong and his cabal of theorists can help me read the mind of an actual living individual?)

“Capt. Westbrook needed to find Oswald and make sure that he arrived at the Texas Theater,” Armstrong writes. “The most likely place to look for HARVEY Oswald [one of Armstrong’s dual-Oswalds] was his rooming house on North Beckley.” [30]

By all accounts, no one knew where Lee Harvey Oswald was living in Oak Cliff at the time of the assassination – not even Oswald’s wife Marina – and Armstrong offers nothing here to support his claim that Captain Westbrook did.

Anyone familiar with the assassination story can see where Armstrong is going with this – Westbrook and Croy are bound for Oswald’s rooming house driving Dallas police car No.207. [31]

Seven days after the assassination, housekeeper Earlene Roberts claimed that such a car honked its horn in front of the rooming house while Oswald was inside. I’ve written more than enough about this episode in the past to make me delirious and don’t propose to repeat it all here. Suffice it to say, nothing supports Mrs. Roberts claim. [32]

But that hasn’t stopped the endless speculation about Mrs. Roberts’ nebulous assertion which makes it perfect for Armstrong’s equally nebulous speculation that attempts to tie all of the loose-ends in this portion of the assassination story into a nice package labeled: Conspiracy! – complete with a bow on top.

Commercial actress Clara Peller once asked, “Where’s the beef?” Here, Armstrong offers nothing but filler hidden under two tiny pickles atop his nothing burger.

Armstrong pretends to identify the driver of Car No.207 as James M. Valentine, based on news film that shows Valentine’s vehicle arriving in front of the Depository with Dallas Morning News reporter James Ewell and Dallas police sergeant Gerald L. Hill.

But anyone familiar with this episode knows that nothing in the news film identifies the officer driving as Valentine, and that the identity of the driver of Car No.207 – which is indeed Officer Valentine – comes from numerous Dallas police and FBI reports – one of which Armstrong reproduces within his own article. [33]

Fabricated cover-up

Furthermore, Armstrong fabricates a cover-up where none existed. Armstrong writes that “Officer Valentine had the keys to car #207, and likely gave those keys to a fellow officer prior to 1:00 PM, likely to Sgt. Stringer, Sgt. Croy or to Westbrook.” [34]

To build even more drama, and raise the specter of a cover-up, Armstrong writes, “Jimmy Valentine was never investigated nor questioned. Why not? Valentine should have been interviewed by DPD internal affairs, the FBI, the Secret Service, and/or the Warren Commission and asked who borrowed his squad car that afternoon? Valentine should have provided a written statement or affidavit as to either the location of car #207 or the officer to whom he gave the keys to car #207 prior to 1:00 PM on 11/22/63. The opportunity to identify and connect the police officers in car #207 with HARVEY Oswald (one of Armstrong’s dual-Oswalds) was now lost, and I believe was intentionally lost.” (emphasis by Armstrong) [35]

How could such an obvious cover-up be contained, you ask? Armstrong supplies the answer:

“To resolve this problem (cover-up this problem),” Armstrong assures us, “a brief ‘letter of explanation’ was prepared and given to Chief of Police Jesse Curry, who then forwarded this letter to the Warren Commission. This ‘letter of explanation’ claimed that car #207 was parked at the Book Depository all afternoon. But this letter was not written by Officer Valentine, or his Sergeant, or his Lieutenant, or his Platoon Commander (Capt. Cecil Talbert). This letter was prepared and signed by the man in charge of the personnel department – Capt. W.R. Westbrook – the man who I believe drove car #207 past Oswald's rooming house (with Sgt. Croy) and was seen by Earlene Roberts.” (emphasis added by Armstrong) [36]

At this point, Armstrong reproduces the ‘letter of explanation’ and notes that not only was Valentine not questioned, but “Sgt. J.A. Putnam was never questioned about his receiving keys to police cars at or near the TSBD.” [37]

Ah-ha! The proverbial fox-guarding-the-henhouse scenario. What could be more devious? As you might have suspected, it’s all a pile of road apples – and Armstrong knows it.

The Dallas police investigation was touched off by a lead supplied by the FBI concerning a statement given by Earlene Roberts on November 29, 1963 – seven days after the assassination. [38]

That memo led to a statement being submitted by Officer Valentine, dated December 2, 1963, in which Valentine identified himself as the driver of Car No.207; stating that he drove to the Depository to aid in the search of the building; and that he turned his keys over to Sgt. J.M. Putnam at the Depository, adding, “I never did drive to Oak Cliff.” [39]

On December 4, 1963, Westbrook submitted a memo regarding Valentine’s statement adding that in addition to Valentine’s car keys, Sgt. J.A. Putnam collected keys from other cars parked in the immediate vicinity and that the keys were released to the Third Platoon Commander, Capt. James A. Souter, at City Hall at approximately 3:30 p.m. on November 22, 1963. [40]

On December 23, 1963, Captain O.A. Jones submitted a memo to Chief of Police Jesse E. Curry, describing the results of the investigation into Car No.207. [41]

It was never determined what police car, if any, drove passed the rooming house at 1026 N. Beckley, as reported by the housekeeper. My own investigation into this incident, reported in my 1998 book, “With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit”, raises grave questions about whether it happened at all. No doubt the Dallas cops thought the same thing.

The fact that all of this information has been well-known to assassination researchers for the better part of fifty-years apparently escaped the investigative eye of John Armstrong. Or did it?

In addition to the internal Dallas police investigation, the FBI conducted an exhaustive investigation of the incident, initiated by a May 19, 1964, letter from the Warren Commission. The FBI checked out the occupants of three dozen squad cars with a focus on anyone that might have been in the vicinity of Oswald’s rooming house. During that investigation, Officer Valentine was again interviewed. He reiterated that his car was not driven by anyone between the time of his arrival at the Book Depository building and his departure, sometime between 4:00 to 4:30 p.m. [42]

None of these investigative efforts is revealed by Armstrong to his readers. Instead, he charges that “Jimmy Valentine was never investigated nor questioned.” [43] What a joke.

Rendezvous on Beckley and murder on Tenth

In Armstrong’s fantasy conspiracy, Captain Westbrook and reserve Sergeant Croy drive passed Oswald’s rooming house and toot their horn, signaling Oswald to come out and climb into their car with them. [44] Their newly revised plan?

According to Armstrong, “Westbrook then drove Oswald to the deserted alley behind the Texas Theater, less than a mile away, and arrived about 1:03 PM. During this short trip Westbrook may have given HARVEY Oswald (again, one of Armstrong’s dual-Oswalds) a .38 caliber revolver that was later taken from him when he was arrested.” [45]

Unfortunately, for the poor hapless “Oswald” in Armstrong’s tale, the “real reason for sending Oswald into the theater was to make it appear as though he was hiding from police…” [46] Oh, my! Whatever are they planning?

“After dropping HARVEY Oswald off in the deserted alley behind the Texas Theater,” Armstrong writes, “Westbrook and Croy drove police car #207 six blocks east thru the same alley and, after passing Patton St., turned left onto a very narrow driveway between two houses at 404 and 410 E. 10th.” [47]

They arrived around 1:05 p.m., Armstrong assures us, and by then, Officer J.D. Tippit had been parked on Tenth Street at the foot of the same driveway for “a minute or two.” [48]

Tippit had “shut down” the engine of his car and was already quietly conversing with LEE Oswald (the evil twin of the “Oswald” dropped off behind the Texas Theater – I know, it's all crazy-talk, but bear with me), when Westbrook and Croy pull onto the driveway via the alley. [49]

“But Tippit did not know.” Armstrong writes, “that LEE Oswald’s assignment was to shoot and kill him.” [50] Armstrong doesn’t tell us why Tippit had to die.

“I believe that when Officer Tippit saw the police car stop between the two houses,” Armstrong writes, “he got out of his car and began walking toward the police car for a pre-arranged meeting with Capt. Westbrook.” [51]

According to Armstrong, Captain Westbrook also climbed out of his car, Car No.207, and began walking down the driveway toward Tippit’s car. As Tippit reached the left-front fender of his squad car, LEE “Oswald”, pulled out a .38 caliber revolver and fired three shots into him - all under the watchful gaze of Westbrook.

Armstrong then suggests that it is Captain Westbrook who orders “Oswald” to return and “finish the job, make sure he’s dead.” [52] “Oswald” dutifully returns and fires a fourth shot into Tippit’s head.

According to Armstrong’s delusion, all of this occurs between 1:00 and 1:06 p.m. – far too early for the real Lee Harvey Oswald (whom Armstrong refers to as HARVEY in his book) to make it on foot from his rooming house to the shooting scene.

This is all alleged in order to exonerate Oswald (the real one, in case you’ve lost track) from Tippit’s murder because – according to Armstrong – the real and unwitting Oswald is dutifully waiting in the Texas Theater for his intelligence “contact” on orders from Captain Westbrook, unaware that he is about to be murdered by a cabal of vengeful Dallas police officers.

How about a little sanity?

Let’s stop for a moment and catch our breath.

First, and foremost, not one single word of what you just read – which comprises the entire section above – is supported by anything other than Armstrong’s demented imaginings.

I wrote the book on this case twenty-two years ago (with an expanded update in 2013). “With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit” contains more documented facts about what transpired on Tenth Street than anything written before or since.

I came at the case in 1983 thinking there might have been a conspiracy to frame Oswald for the murder. After looking under every rock and shaking every bush, I came to realize that Oswald was guilty. That was my 20-year journey; yours may vary.

Charlatans like Armstrong are a dime-a-dozen and none of them have come close to shaking the foundation of the case against Oswald for the murder of Tippit. None of them.

I’m not going to try to argue the entire Tippit case here in a few short paragraphs. It would be a disservice to history and to the man. Do yourself a favor. Borrow my book from a public library and read it yourself. It’s free.

The basics

To make my point here, I’ll simply state the basic facts as I found them: At approximately 1:14 p.m., Officer J.D. Tippit pulled up alongside Lee Harvey Oswald walking down Tenth Street in Oak Cliff. Oswald walked over to the passenger side of the car, leaned down, and spoke briefly to Tippit through an open vent window. The conversation lasted ten to fifteen seconds. Tippit then emerged from his car and walked toward the front, as if he were going to question Oswald further. Suddenly, Oswald stepped back, pulled a .38 caliber revolver from under his jacket and fired five quick shots over the hood of the car, four of them striking Tippit. The officer fell to the pavement, dead. Oswald fled the scene, reaching the house on the corner of Tenth and Patton in about thirty-seconds. He was seen unloading his revolver as he passed the corner house, and headed south on Patton Avenue.

The consensus of the majority of eyewitnesses was that only one man was involved in the shooting. That man was identified by the vast majority of those who witnessed the shooting, or saw the man fleeing the scene, as Lee Harvey Oswald (1939-1963). Forensic evidence supports this conclusion. Period.

Fungus amongus

Lies and distortions are like fungus – they spread rapidly when unchecked. Armstrong & Company have been having a high-old time for years with the Tippit story. In books, blog posts, and research conferences, the nonsense purveyors have been spreading their brand of bile with impunity.

It’s time to spray a little Roundup ® on the fungus covering the historic truth of this sad and simple event. Let’s step back now and take a hard look at the sources – or lack thereof – in this latest retelling of the Tippit murder.

Beating an old drum

According to Armstrong’s timeline, Tippit was gunned down at 1:06 p.m. – an old drum that conspiracy theorists have been beating since 1963 in their bid to exonerate Oswald for the crime.

I’ve written about the time of the Tippit murder more than once – most recently in 2017 [53] – and have proven in spades that Tippit was murdered between 1:14 and 1:15 p.m.

But that hasn’t stopped conspiracy folks from abandoning logic, reason and a mountain of evidence to claim that Tippit was shot earlier.

In this instance, Armstrong claims that seventeen eyewitnesses to the murder or its aftermath support the 1:06 p.m. shooting time – Frank Cimino, Francis Kinneth, Elbert Austin, Domingo Benavides, Helen Markham, Margie Higgins, Mary Wright, Mrs. Ann McCravey, Doris Holan, Acquilla Clemons, Roger Craig, Barbara Jeanette Davis, Virginia Davis, William Scoggins, L.J. Lewis, T.F. Bowley, and J.C. Butler.

But Armstrong’s claim is demonstratively false! In just a few hours, I pulled together enough real, honest-to goodness evidence to deep-six Armstrong’s entire list forever. Here’s what Armstrong was unable to find (or unwilling to report):

Seventeen fabricated witnesses

Frank Cimino told the FBI he heard shots “around 1:00 p.m.” [54] Armstrong never divulges how he determined that the word “around” meant a precise time – six-minutes after one o’clock – as opposed to 12:45 p.m., or 1:15 p.m., or any number of other times at or “around” 1:00 p.m.

Francis Kinneth told the FBI that he heard shots “at approximately 1:00 p.m.” [55] Again, Armstrong fails to explain how Kinneth’s approximation becomes a precise time.

Elbert Austin (Armstrong refers to him incorrectly as “Albert”) told the FBI that he heard shots “sometime after 1:00 p.m.” [56] In an effort to gin up Austin’s testimony, and bring it in line with his proposed 1:06 p.m. shooting time, Armstrong changes Austin’s testimony to “shortly after 1:00 p.m.” [57]

Domingo Benavides told the Warren Commission that he “imagines it was about one o’clock” when Tippit was shot. [58] Pressed further, Benavides said, “It was after lunch. I had already eaten. It was after I had lunch and I had eaten around 12, somewhere around 12 o’clock.” [59] Armstrong doesn’t even bother to mention any of this, of course. He simply attributes “1:06 p.m.” to Benavides’ story and leaves his readers to figure out that it is all a lie.

Helen Markham told the DPD on November 22, 1963, that the shooting occurred at “approximately 1:06 p.m.” [60] Later that same day, Markham told the FBI that the shooting occurred “possibly around 1:30 p.m.” [61] In April, 1964, she told the Warren Commission, “I wouldn’t be afraid to bet it wasn’t 6 or 7 minutes after 1.” [62] Markham’s estimate of the shooting time has been discussed until we’re all blue in the face (a good dissection presented HERE [63]), but it’s worth noting , again, that the conspiracy folks love to argue that Markham is an “utter screwball” when it comes to her description of the shooting and her identification of Oswald as the killer, but she’s rock-solid on the time. And here, Armstrong doesn’t disappoint his fans.

Margie Higgins (aka Mrs. Donald R. Higgins) reportedly told author Barry Ernest in 1968 that she heard shots at 1:06 p.m., and was certain of the time because she was watching the news on television and “for some reason the announcer turned and looked at the clock and said the time was ‘six minutes after one.’ He said it just like that, ‘six minutes after one.’ And you know how you always do, you hear the time and you automatically check your own watch. So, I just looked up at the clock on my television to verify the time and it said 1:06. At that point I heard the shots.” [64] Unfortunately for Mrs. Higgins (and apparently Mr. Earnest, who didn’t bother to check out her story), none of the three networks broadcasting that afternoon in Dallas gave a time check at 1:06 p.m. as she claimed. But that didn’t keep Armstrong from deceiving his readers and listing her as one of his 1:06 p.m. shooting witnesses.

Mary Wright is also listed as a “1:06 p.m.” shooting witness by Armstrong who writes that Mrs. Wright telephoned police within seconds of the shots, was connected with the push of a button to the ambulance dispatcher at the Dudley Hughes Funeral home located two blocks away, and an ambulance was dispatched to the scene. But Armstrong never mentions that the call was clocked in at the Dudley Hughes Funeral home at 1:18 p.m., [65] or that the ambulance reported that they were en route to the scene at 1:18:38 p.m., [66] or that they arrived twenty-one seconds later, [67] or that at 1:19:15 p.m., police broadcast Mary Wright’s address to officers racing to the scene. [68]

Mrs. Ann McCravey (aka Mrs. Charles McRavin) is described as shouting, ‘Oh, he’s been shot!’ during the 1:06-1:07 p.m. time interval. Armstrong writes that she was never interviewed by the Dallas police, the FBI, or the Warren Commission. So where does the time interval being cited come from? Armstrong tells readers that Mrs. McRavin was interviewed by the BBC, but fails to mention that the recorded interview he cites never mentions any time frame for the shooting. [69] Again, instead of truth, we are fed more lies.

Mrs. Doris Holan, we are told by Armstrong, “had just returned home from her job after 1:00 PM when she heard several gunshots.” However, according to those to who claimed to have interviewed Mrs. Holan, she had returned home at 7:30 a.m., not one o’clock, and went to sleep (after working all night). She reportedly awoke at “1:12 p.m. – 1:14 p.m., somewhere in that neighborhood”, lit a cigarette, and while smoking it, heard four shots. [70] Here, again, Armstrong falsifies the original story – and it is a whopper of a story – more to come later.

Mrs. Acquilla Clemons is also counted as a 1:06 p.m. shooting time witness despite the fact that she told Mrs. Shirley Martin, in a recorded interview, that the Tippit shooting happened in the morning at about 11:30 a.m., and that Mrs. Clemons had already heard that President Kennedy had died of his wounds in the assassination – a fact not broadcast to the general public until 1:35 p.m. [71] Obviously, Mrs. Clemons didn’t have any idea what time to the Tippit shooting occurred. So, why does John Armstrong list Clemons as a 1:06 p.m. shooting time witness? Obviously, he must think his readers are too stupid to know any better.

Deputy Sheriff Roger Craig is also listed as a 1:06 p.m. shooting time witness. Craig claimed that while he was on the sixth-floor of the Book Depository, an officer informed Captain Fritz of the shooting in Oak Cliff. “I instinctively looked at my watch. The time was 1:06 PM.” Craig is all over the map on this one, although you’d never know it reading anything Armstrong wrote. In 1968, Craig told Penn Jones that he was outside the depository and heard a broadcast about Tippit’s killing. Asked what time Tippit was killed, Craig said, “It was about 1:40 p.m.” When Jones corrected him and said the shooting was a little before 1:15 p.m., Craig said, “Oh, that’s right. The broadcast was put out shortly after 1:15 p.m. …” [72] Three years later, Craig’s memory improved. Now, he was on the sixth-floor of the Depository and his watch said 1:06 p.m. How would you know any of this reading John Armstrong’s nonsense?

Barbara Jeanette Davis told the Dallas police on November 22, 1963, that she heard shots “shortly after 1:00 p.m.” [73] Davis told the Secret Service on December 1, 1963, that she heard shots “a few minutes after 1:00 p.m.” [74] In March 1964, Davis told the FBI that “shortly after 12 noon” she put her children to bed for a nap and “approximately 15 to 30 minutes later” she heard gunshots. [75] (That would place the shooting at some time between 12:20 and 12:40 p.m.) When she testified to the Warren Commission two weeks later, Davis said that she “didn’t pay any attention to what time it was” when the shooting occurred. [76] So much for Armstrong’s 1:06 to 1:07 p.m. guesstimate.

Barbara’s sister-in-law, Virginia Ruth Davis, didn’t fare any better, but what does it matter to people like Armstrong? While he lists Virginia as supporting a 1:06 to 1:07 p.m. shooting time, he quotes her Warren Commission testimony in which she states that the shooting occurred “between 1:30 and 2 p.m.” [77] By then, she had already told the Dallas police that the shooting occurred “about 1:30 p.m.” [78], the Secret Service the same, [79] and the FBI “between 1 and 2 p.m.” [80]

Cab driver William Scoggins is also listed as a 1:06 p.m. shooting time witness. Armstrong assures us that Scoggins called his dispatcher after Oswald fled, and the dispatcher called for an ambulance which arrived within two minutes. Armstrong writes, “The taxi company dispatcher was probably the 4th citizen to call to the police (circa 1:07-1:08 p.m.).” [81] Of course, Armstrong doesn’t bother to mention that the taxi cab dispatcher recorded the call from Scoggins as coming in at 1:25 p.m., though the dispatcher acknowledged that he first called the police before recording the time of the call and that the time reflected on the message was probably “delayed”. [82] Nor does Armstrong mention that the ambulance arrived at the shooting scene at 1:19 p.m., [83] which by Scoggins account, means that Oswald passed his cab two-minutes earlier – at about 1:17 p.m. Nor does Armstrong acknowledge that Scoggins testified to the Warren Commission that the shooting occurred “around 1:20 in the afternoon.” [84] To do so would betray the lie that Armstrong had constructed around Scoggins’ actual version of events.

L.J. Lewis is yet another one of Armstrong’s 1:06 p.m. witnesses, citing Lewis’ call to police after observing Oswald running down Patton Avenue. Armstrong pegs the call at 1:07 to 1:08 p.m., however, Lewis himself never assigned a time to the shooting – only that he made the call as he saw Oswald turn west on Jefferson in an effort to flee the scene. [85]

Temple Ford (T.F.) Bowley reported that he looked at his watch when he arrived on the Tippit scene and it read: “1:10 p.m.” Conspiracy believers have readily accepted Bowley’s time-check as true and accurate despite considerable evidence that his watch was wrong. (Read all about it HERE.) In this go-around, Armstrong claims to have “An original DPD police transcript, found in the National Archives, [that] lists the time of Bowley’s call to the police as 1:10 PM. Bowley’s voice can be heard on the police Dictabelt and his report to the police dispatcher is written on the DPD police transcript.” [86] Naturally, Armstrong doesn’t produce a copy of his discovery, so allow me to make my position clear on this so-called new find – bullshit! (See the section, ‘Altered evidence’ below for a complete discussion.)

J.C. Butler, the ambulance attendant who drove Tippit’s body to Methodist Hospital, is also added to Armstrong’s list as a 1:06 p.m. shooting time witness. When asked by HSCA investigators in 1977 how long he was at the shooting scene, Butler replied, “I was on the scene one minute or less. From the time we received the call in our dispatching office until Officer Tippit was pronounced dead at Methodist Hospital was approximately four minutes.” [87] Armstrong quotes this source, then adds: “circa 1:13-1:14 p.m.” [88] as if Butler’s arrival at Methodist occurred at that time. Yet, as we’ve already show, the Dudley Hughes Funeral Home dispatch office time stamped the call for an ambulance to the Tippit scene at 1:18 p.m. [89] Dallas police radio recordings show the ambulance arriving at 1:19 p.m. [90] and departing at 1:20 p.m. [91] Butler’s last radio transmission, presumably his arrival at Methodist Hospital, was made at 1:24 p.m. [92] Total elapsed time: 6 minutes, which compares favorably with Butler’s 14-year-after-the-fact estimate of 4 minutes. But, of course, all of the actual times occur long after Armstrong’s fantasy time frame of 1:09 to 1:14 p.m.

This is not the first time I’ve written about the time of Tippit’s death – a rather basic fact to establish in any murder case – and unfortunately, I doubt it will be the last. Frankly, it is impossible to keep up with all of the people willing to lie in order to sell a conspiracy where none exists. Armstrong’s writings are proof that this case attracts not only the crazy people, but the really crazy people.

Altered evidence

In an effort to substantiate the fabricated testimony of his seventeen shooting-time witnesses, Armstrong trots out another moldy claim – the Dallas police radio transcripts have been altered. Yikes!

In this convoluted argument, Armstrong claims that T.F. Bowley reported the shooting at 1:10 p.m., as shown in an early transcript (so says Armstrong), but that the Dallas police had to alter the recordings and the transcript to show that Bowley’s transmission was made at 1:18 p.m. – thus giving Oswald time to get to the scene. [93]

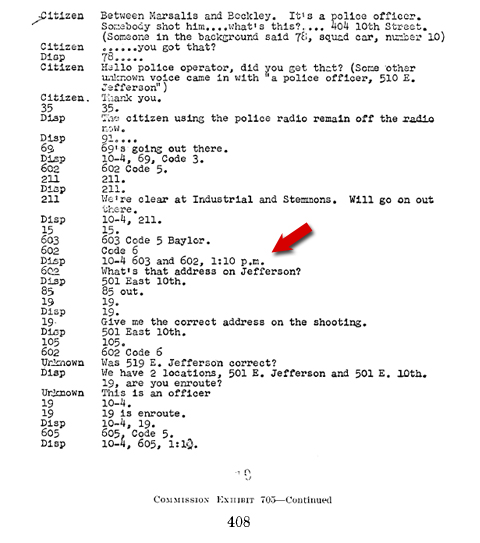

Armstrong spends a lot of time here attempting to convey his point which really never comes together. The best he could offer was a page from the transcript made available by Dallas Police Inspector J. Herbert Sawyer on March 20, 1964.

That transcript shows a time check of “1:10 p.m.” being given by the dispatcher shortly after Bowley concluded his transmission and while the Dudley Hughes ambulance was racing to the shooting scene. [94]

|

Fig.1 - DPD transcript (CE 705) showing 1:10 p.m. time check (red arrow) which is an obvious typo.

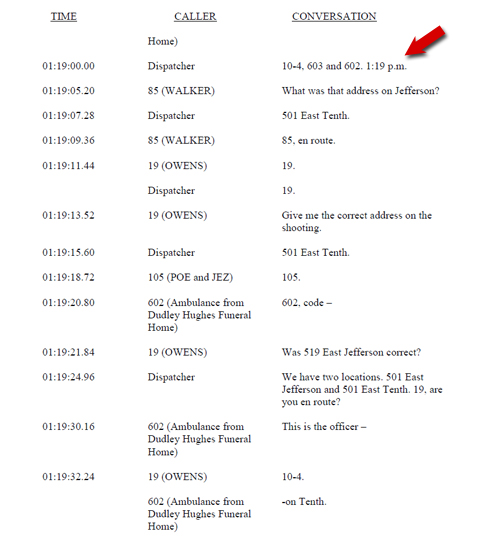

When one listens to the actual recordings, however, the dispatcher clearly says, “1:19” where the police transcript shows “1:10 p.m.” [95]

|

Fig.2 - Transcript of the actual recordings showing the correct 1:19 p.m. time check (red arrow).

If you believe Armstrong, the conspirators were too stupid to alter the transcript after altering the recordings.

Or, if you were a reasonable person, you might suspect that the 1:10 p.m. citation was a typo, given the fact that the dispatcher time checks leading up to the “typo” were: 1:11, 1:15 and 1:16 p.m. The dispatcher time checks that followed were: 1:19, 1:22, 1:23 p.m. and so on. And yes, the actual recordings match the transcript time checks. (Why is this so hard?)

What does Armstrong offer as proof of alteration?

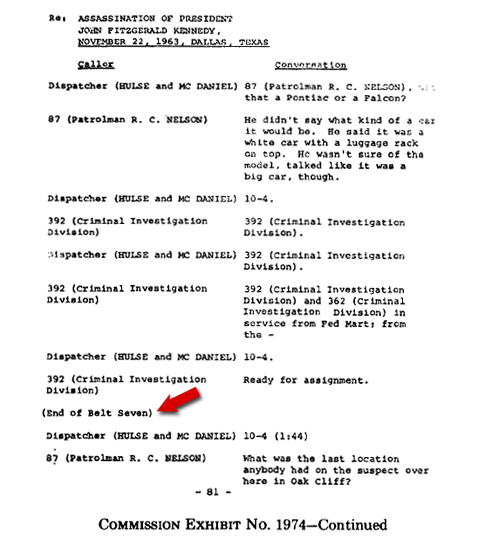

“At 1:44 p.m. the FBI created transcript (CE1974) reads ‘Tape splice’,” Armstrong writes – and here, Armstrong refers readers to a graphic illustrating his point, rather than the actual Commission exhibit. The reason he did this will become evident in a moment.

“A ‘tape splice’ or splice of any kind,” Armstrong continues, “cannot be made to a Dictabelt or vinyl disk. This notation is proof that DPD dispatch recordings on the original DPD Dictabelts and/or vinyl disks were copied onto a tape recorder. The tapes of dispatch recordings were then altered by removing/cutting sensitive portions of the tapes and then splicing portions together (‘tape splice’). The altered tapes were then played and recorded onto a Dictabelt machine, and the resulting Dictabelts and disks were returned to the DPS.”

Ah, ha! The “tape splice” means the recording was edited. Or does it? The reason Armstrong doesn’t show his readers Warren Commission Exhibit (CE) 1974 is because it contains the notation “End of Belt Seven” at the point where Armstrong claims there is a sinister splice.

|

Fig.3 - FBI transcript showing "End of Belt Seven" notation (red arrow).

Again, the actual recordings show a slight overlap between the end of Dictabelt seven and the beginning of eight – as one Dictabelt machine reaches the end of the belt and the second machine begins recording. (The overlap was designed so that a continuous recording could be maintained.)

Finally, Armstrong notes that even Captain James C. Bowles, the radio dispatch supervisor at the time, told the Sixth Floor Museum archivist Gary Mack, back in 1982, that he could not give any assurance that the Dictabelts which were returned to him by the FBI were the same ones which left the possession of the Dallas Police – a perfectly reasonable statement to make. [96]

However, it is equally reasonable to believe that the Bowles’ inability to give his assurances did not necessarily mean that the Dictabelts had been tampered with. Armstrong certainly hasn’t offered anything to support such a claim, except of course his own self-serving beliefs.

Given his penchant for distorting the truth, Armstrong is hardly a credible source for anything related to this case.

Doris E. Holan

The alleged primary witness to Armstrong’s cock-n-bull story is Doris E. Holan, a waitress working at the Marriott Hotel in Dallas in 1963, who by chance, happened to witness two despicable cops – Westbrook and Croy – arranging the murder of a fellow officer in broad daylight right outside her door. Or, so we are told.

Mrs. Holan’s story first surfaced in Harrison E. Livingstone’s 2004 book, “The Radical Right and the Murder of John F. Kennedy: Stunning Evidence in the Assassination of the President”.

Nine years later, Joseph McBride’s self-published book: Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J.D. Tippit (Hightower Press, Berkeley CA., June, 2013) referred to the importance of Holan’s account while cautioning that Holan “gave her account long after the event, and such accounts are subject to skepticism.” [97]

McBride’s feigned skepticism didn’t stop him however from treating Holan’s account as fact, apparently with little more than the assurances of self-proclaimed Dallas researcher Michael G. Brownlow and his side-kick, retired Southern Methodist University (SMU) Professor William J. “Bill” Pulte – the original source of the Holan claims.

In fact, no one in the so-called JFK research community – including Brownlow and Pulte – seemed interested in finding out whether Doris Holan’s claims had any validity. It was so much easier to simply embrace anything that supported the “big conspiracy” no matter how absurd the claim might be.

New levels of absurdity

In May, 2016, the two-Oswalds theorist and author, John Armstrong (Harvey and Lee), took the Holan story to new levels of craziness. [98]

In an announcement posted on the UK Education Forum, Armstrong webmaster Jim Hargrove wrote: “Two Dallas cops were involved in the pre-arranged murder of Tippit and the framing of Oswald. Evidence newly compiled by John Armstrong shows that two DPD policemen, Captain W.R. Westbrook and reserve officer Kenneth Croy, were intimately involved in the murder of J.D. Tippit and the framing of ‘Lee Harvey Oswald’ for the assassination of JFK. This information is contained in a major update to the ‘November 22, 1963’ page at the Harvey and Lee Website, which I just put up a few hours ago.” [99]

And, of course, Captain Westbrook was CIA. Oh, didn’t you know?

Armstrong writes: “Following the assassination of President Kennedy, Westbrook relocated to South Vietnam where he was a CIA-sponsored advisor to the Saigon Police Dept. Now we finally realize and understand that Westbrook was working for the CIA, the agency in which rogue hi-level individuals such as David Atlee Phillips, E. Howard Hunt, and likely Allen Dulles planned and carried out the assassination of President Kennedy. There is no doubt, at least in my mind, that Capt. Westbrook, and to a lesser degree Sgt. Croy, were deeply involved as co-conspirators. The one important, unanswered question is the identity of Westbrook’s CIA contact and co-conspirator.” [100]

What is Armstrong’s source for this accusation? It comes from a postscript that follows an interview of W.R. Westbrook, published in Larry A. Sneed’s 1998 book, No More Silence:

“Captain Westbrook retired from the Dallas Police Department in 1966 and later served as a police adviser in South Vietnam…” (emphasis added) [101]

How does being a police adviser in South Vietnam turn into working for the CIA? According to the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Foreign Relations (93rd Congress): “… (Vietnamese police) officers said they and their staffs met frequently with the Saigon station chief of the CIA and his staff…” [102]

However, the citation refers to a February 25, 1974, New York Times article discussing the continuing American involvement in South Vietnam after the Paris accord ceasefire in 1973, and has nothing to do with Westbrook’s assignments or duties in 1966.

It’s been no secret that Westbrook resigned the Dallas Police Department in August, 1966 and took a job overseas with the U.S. Agency for International Development and served as a police adviser in South Vietnam. Police colleagues and reporters besieged the captain with reasons why he should forget the offer to go to war-torn southeast Asia. He went anyway. [103]

But what he did there and who he reported to is not known – there are no public records available – no matter how much red-meat Armstrong & Company toss out in an effort to insinuate a relation between Westbrook and the CIA in 1963.

Maybe Westbrook had contact with CIA officers in South Vietnam as part of his duties and maybe he didn't. Frankly, Armstrong & Company are guessing and as we’ve already seen, they’re shitty guessers.

So, what is the primary evidence for Armstrong’s Westbrook-Croy plot to murder Tippit and frame Oswald?

According to Armstrong, the proof of the plot hinges almost entirely on Doris Holan, who happened to witness the supposed plot unfolding right before her eyes as she watched from a second-story apartment window on Tenth Street. Or, so we’re told.

Tracking down the truth

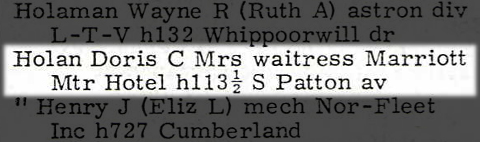

Oddly enough, the Dallas City Directory shows Doris E. Holan living at 113 ½ S. Patton Avenue in the fall of 1963. [104]

|

Fig.4 - Dallas City Directory listing for Doris E. Holan (the middle initial 'C' is incorrect).

Why then, did Brownlow and Pulte say that Holan was living around the corner on Tenth Street? What did they know that they haven’t told us?

It was simple enough to find out, I thought. I emailed Professor Pulte, and asked him: “Dear Mr. Pulte – I’m working on an update to my book “With Malice” and am interested in the Doris Holan story. I understand you interviewed her with Michael Brownlow. Are there any recordings or transcripts of your interviews with her or any documentation that supports her story that would be available to me?” [105]

Answer? Chirp-chirp-chirp – crickets. Professor Pulte never responded to my query. That wasn’t completely surprising given the level of paranoia in the “research community” and the content of a 1999 letter from Pulte to High Treason author Harrison E. Livingstone, in which the professor accused me of being a “political propaganda specialist” bent on creating a “phony positive image” about Officer Tippit with my book, With Malice.

Not only did the professor have a full hate on for me, but his paranoia drove him to worry that criticizing me might prove harmful.

“Harry, you may use my name in citing information which I have sent you,” Pulte wrote, “but not when I am criticizing Myers. Since I have to live in Dallas, to attack him head-on might be unwise.” [106]

Wow. I found the letter rather amusing. After all, what did the learned professor think I was going to do?

Absent a response from Professor Pulte, I began assembling every scrap of information I could find in the public record about the Holan interviews conducted by Pulte and Michael Brownlow.

Curiously absent from this collection was how they became aware of Mrs. Holan in the first place? Usually, this is one of the more interesting parts of a story – i.e., “You’ll never believe how I found this woman thirty-seven years after the fact…”

Additionally, how did they find out she was living in a nursing home? And more important, not being family members, how did they gain access to her in the nursing home? I assume the nursing home wasn’t letting just anyone drop in and visit one of their residents? Did a family member escort them into the home? Who was it?

Something stinks

One thing I immediately noticed when reading the various accounts of the Holan interview was the level of detail researcher Michael Brownlow provided when discussing statements allegedly made by Holan and others he had supposedly interviewed over the years.

In the course of my radio and television career, I’ve conducted hundreds of interviews. No one – and I mean no one – talks the way Mrs. Holan supposedly talked to Brownlow. Frankly, people just can’t remember the level of detail Brownlow claims that Mrs. Holan was able to provide him during his interviews, especially thirty-seven years after the fact. People just don’t talk like that.

Interviews are normally filled with “I don’t knows”, “maybes” and “I don’t remembers” – along with a generous helping of “ahhs”, “ums” and blank stares.

Now, obviously, I wasn’t there, so I won’t say that Brownlow’s account is largely a fabrication – but it sure sounds like one to me.

Which brings me to a second point. Why have we not seen a transcript or heard a recording of this interview? Either one would go a long way toward establishing the validity of Pulte and Brownlow’s claims. And don’t tell me they don’t have one!

I’ve recorded and transcribed every single interview I ever conducted in this case for the simple reason that someone might challenge a claim I might make based on those conversations.

Good Lord, in a controversial case that has gotten worldwide attention for nearly six decades, you’d better be prepared to back up your claims and anyone who pretends they didn’t know that simply isn’t credible – especially individuals like Pulte and Brownlow, who insist that they’ve interviewed more eyewitnesses in this case than anyone alive.

Finally, I noted multiple discrepancies between what I know to be true, based on my own interviews, and what Michael Brownlow claimed he was told by Barbara Jeannette Davis, her sister-in-law Virginia Ruth Davis, cab driver William W. Scoggins, and little-known eyewitnesses like Frank Cimino – to name just a few. Many of those discrepancies raise serious questions about whether Brownlow had actually spoken to them, as he claimed. In fact, Brownlow’s re-tellings are sprinkled with so much obvious bullshit that it’s hard to take any of it seriously.

A seven-month investigation

In an effort to learn the truth about the Doris Holan story, once and for all, I conducted an exhaustive probe into her claims.

The result of that seven-month investigation – released earlier this week, and detailed HERE – conclusively shows that Doris E. Holan was living in a second-floor apartment at 113 ½ S. Patton Avenue, right around the corner from the Tippit murder scene, on November 22, 1963, and didn’t move to the Tenth Street apartment cited in Armstrong’s fantasy until 1964 – well after the assassination.

I know there will be a lot of gnashing of teeth in conspiracy-town this week, but there you have it. Pass the handkerchiefs and may I say, ‘boo-hoo.’

Frankly, I don’t know that anyone should be surprised. The Pulte and Brownlow claims were hard to swallow from day one. And John Armstrong’s fantasy cabal, heaped on top, didn’t make it any easier to digest.

There’s plenty more I could say about this sorry episode, but I promised at the beginning to make my rant shorter, rather than longer.

For the die-hards who just can’t get enough historic crapola in their diet, rest assured there will be new accusations to ponder, no doubt. There always are in a case dominated by loud-mouthed charlatans hawking their own peculiar brand of snake-oil.

A special place

Lately, accusing public servants of being enemies of the state has become the new normal, and let’s face it, it’s so much easier to accuse the dead who can neither defend their good name or sue their accusers into the poor house.

But when you charge the dead with being part of plot to assassinate an American president and murder a police officer – both rather despicable crimes; one a matter of treason – you’d better have something more than your sick fantasies to back it up, lest there be a special place in Hell reversed in your honor. [END]