by DALE K. MYERS and TODD W. VAUGHAN

Flash 8 or higher is required to view videos accompanying this article. Get the free plugin now.

In February, 2007, author Max Holland and Johann W. Rush posited that Lee Harvey Oswald fired his first shot earlier than anyone had ever suspected – before the famous Zapruder film even began churning through old Abe’s 8mm Bell & Howell camera.

After evidence for their theory was examined and debunked by these authors in Max Holland’s 11 Seconds in Dallas, Seattle attorney and assassination student Kenneth R. Scearce fired back with an independent article aimed at finding fault with our rebuttal and support for Holland’s so-far, unsupportable theory.

Again, Holland’s early shot theory and Scearce’s challenge were debunked in a second article titled, Holland Déjà Vu.

Apparently, Misters Holland and Scearce haven’t had enough. They’re back, this time in a joint effort titled: 11 Seconds in Dallas Redux: Filmed Evidence, which promises readers that several pieces of old evidence turn out to corroborate the suspected early shot after all and that Holland’s theory “should now be regarded as the depiction with the greatest fidelity to all the known facts.”

If it all sounds too good to be true, you’re right; especially when one begins examining the old evidence that Holland and Scearce find so compelling that we’re expected to chuck forty-five years of research into the shooting sequence right out the sixth floor window.

Instead of impressive fact-finding, Holland and Scearce treat readers to a hodge-podge of assumptions, elastic reasoning, and twisted truth – par for the course, I’m afraid, in every attempt to sell this fantasy so far.

I’ll give Holland and Scearce this much, they’re open and honest about cherry-picking the facts to build a case for their theory. More on that later.

Twenty months after first publishing their theory, and in the wake of two thorough rebuttals which pointed out the fallacy of their claims, Holland and Scearce finally decided to take “a fresh look” at all the amateur films made of the president’s limousine in Dealey Plaza and test them against their own hypothesis.

It seems a little odd to be testing one’s hypothesis after one has announced to the world that the history books should be rewritten, but maybe that’s just me.

According to Holland and Scearce, it’s all okay because the recent testing phase has “unearthed some compelling corroboration” for their early shot theory.

So, what is the earth shattering evidence that has escaped the scrutiny of everyone who has ever examined the shooting sequence so far? The evidence amounts to these four points:

Three Agents

First, Holland and Scearce wrote that “there can be no question” that Secret Service agents John D. Ready, Glen A. Bennett, and George W. Hickey, Jr., were reacting to “a worrisome stimulus” by Zapruder frame Z153.

Why are Holland and Scearce so certain on this point? Because, according to Secret Service protocol, agents assigned to the right side of the presidential follow-up car (like Ready) are supposed to keep their eyes fixed on the area to the right of the car; those of the left toward the left side of the car.

Thus, according to Holland and Scearce, the fact that agent Ready was looking to his left (not his right, per protocol) at frame Z153 could only mean that he was responding to “some kind of stimulus” – translation: he heard a shot.

Really? Does that mean that anytime an agent breaks protocol it can only mean that he is responding to a shot? If that were true, then frames M446-M456 of the Marie Muchmore film would be evidence of a shot being fired as the presidential limousine moved up Houston Street since it shows agent Paul Landis, who is standing on the right running board behind agent Ready, looking to his left instead of his right protocol position.

Figure 1. Enlargement of a portion of Muchmore frame M446.

Isn’t it reasonable that agents aboard the Secret Service follow-up car broke protocol on multiple occasions (if only very briefly) throughout the motorcade’s 39-minute journey through Dallas? And doesn’t that mean that we can’t read too much into agent Ready’s brief leftward glance at the head of the Zapruder film? Or are Holland and Scearce the only ones who can divinely separate those Secret Service agent reactions that correspond to shots and those that don’t?

In addition to their protocol argument, Holland and Scearce assure us that we can actually see agent Ready turn to his left at Zapruder frame Z139, in reaction to their early shot. But can we?

The image of Secret Service agent Ready appears in the sprocket hole area of the Zapruder film between Z133 and Z154. In fact, with the exception of two frames – Z138 and Z139 – agent Ready’s head is not even visible, being obscured by the sprocket hole. It isn’t until frames Z153-154 that we can actually see Ready looking to his left.

So, what about the head turn? There are only two frames – Z138 and Z139 – that suggest that Ready might be turning his head from right to left. I say “might” because we can only see a third of the left side of Ready’s head for one-tenth of a second and even then the image is unduly affected by film artifacts because of its close proximity to the sprocket hole. Suffice it to say, this is hardly the kind of definitive evidence you can take to the bank.

Figure 2. Stabilized sprocket hole area of Zapruder frame sequence Z133 to Z154.

But let’s assume for sake of argument that the film does show Ready turning to his left at about frame Z139, as Holland and Scearce claim. What does the rest of the film reveal? At about Z164, Ready turned to face forward again, then at Z177 snapped his head to the right, and by Z255 had turned sharply to his right-rear (as seen in a photograph by James Altgens).

Figure 3. Portion of James Altgens photograph; equivalent of Zapruder frame Z255.

These filmed actions are consistent with Ready’s contemporary reports. A few days after the assassination, Ready wrote a detailed account of his actions in which he said that upon hearing what he thought were firecrackers “immediately turned to my right rear trying to locate the source.” [18H749 CE1024]

How do Holland and Scearce deal with this contemporary report? They dismiss it, suggesting that Ready’s report was written to conform to the official version of events, having been written after Ready had learned that all three shots had come from Oswald’s perch in the Book Depository.

Holland and Scearce don’t offer any actual evidence (written or otherwise) to support their belief that Ready fudged the truth in his after-action report or why he would even need to hide the fact that he might have looked left instead of right after hearing the first shot. It would appear that it’s simply better for their theory if Ready forgot to mention that initial left turn. How convenient.

The way Holland and Scearce see it, Ready did turn to his right-rear, as he later reported, but only after the second shot, at around Z223. In a footnote, the theorists acknowledge that they don’t really know if Ready turned to his right-rear after the second shot since he disappeared from the Zapruder film a moment earlier, at frame Z208, but thought it unlikely that Ready would have looked back between Z208 and 223. Of course, if the Zapruder film had shown Ready looking back before Z223 their theory would be kaput.

In the end, the image Holland and Scearce paint is one in which agent Ready reacts to an early shot by turning to his left, returns his gaze to the right (his protocol position), then suddenly snaps his head toward the right-rear after hearing the second shot. Later, Ready writes a report that ignores his left-turn reaction to the first shot in order to better fit the Oswald-did-it theory. Yea, sure.

Holland and Scearce’s vision of history is not only a stretch; it’s a bit disingenuous given the filmed record.

The Zapruder film shows agent Ready making a sweeping turn to his right beginning at Z177 and continuing until he disappears into the margins of the film at Z208. (See Figure 4) By then, Ready is looking to his right at a 40 degree angle relative to the midline of the car. Two and one-half seconds later (Z255), Ready had turned another 120-degrees further rearward (as evidenced by the James Altgens photograph). All of this is precisely what Ready described in his after-action report and places the time of the first shot a second or so before Z177. What is so mysterious?

Figure 4. Stabilized Zapruder film sequence - Z133-251.

According to Holland and Scearce, the actions of two other agents – Glen Bennett and George Hickey – support their early shot thesis and corroborate their interpretation of agent Ready’s actions.

Agents Glen Bennett and George Hickey were both seated in the back seat of the Secret Service follow-up car – Bennett on the passenger-side and Hickey on the driver-side.

Bennett wrote, “I immediately, upon hearing the supposed firecracker, looked at the boss’s car. At this exact time I saw a shot that hit the boss about four inches down from the right shoulder; a second shot followed immediately and hit the right rear high of the boss’s head.” [18H760 CE1024]

Holland and Scearce spend time telling us about how “remarkably accurate and succinct” Bennett’s statement is and how they, and they alone, noticed something that no one ever recognized before – Bennett mentioned looking at the president immediately after the first shot.

Turning to the Zapruder film, Holland and Scearce claim that by Zapruder frame Z153, Bennett “had turned his eyes toward the front and tilted his head markedly to the right so he could keep his eye on ‘the boss’;” presumably so he could see around the two front passengers seated in front of him. Holland and Scearce assert that Bennett’s head tilt occurs simultaneously with agent Ready’s left head turn at Z139 and as such is clear, corroborative evidence of an earlier shot.

Really? Let’s back up a minute. First, how in the devil are Holland and Scearce able to see Bennett “turn his eyes” toward the front of the car – or in any direction for that matter – during these earliest Zapruder frame sequences? One can’t even distinguish Bennett’s eyes from his nose in these early, fuzzy frames, let alone determine in which direction he’s looking. (See Figure 2) Even Holland and Scearce acknowledge later in their article, “The film’s resolution simply isn’t sufficient to discern any reflexive responses that probably occurred in reaction to the first, missed shot.”

Second, and of paramount importance, is a fact Holland and Scearce seem to forget in their zeal to break “new” ground – Bennett described how he looked at the president immediately after the first shot and “at this exact time” saw him hit in the back with the second shot.

Doesn’t that mean that Bennett’s remarkably accurate and succinct report was conveying how Bennett turned and looked at the president immediately before the second shot (the shot to Kennedy’s back at about Z223), and not four and one-half seconds earlier. The reason that we can’t ascertain exactly what Bennett did during those four and one-half seconds is because he is hidden from Zapruder’s camera view by Z165. How convenient for Holland and Scearce’s theory.

If the admittedly subtle actions of agents Ready and Bennett don’t convince you of an earlier shot, Holland and Scearce insist, then you’ll certainly be won over by the actions of agent George Hickey, whose movements “cannot be characterized as anything but extraordinary.”

Holland and Scearce assure us that beginning at Z139 agent Hickey can be seen “partially standing up” and by Z153 “beginning to lean way over the driver’s side” of the follow-up car, “almost as if he were looking for something on the ground.” Holland and Scearce believe he was looking for something at ground level, writing, “According to his later statement, Hickey said he thought the initial loud report was a firecracker, and that it exploded at ground level.”

Wait just a moment. First, agent Hickey does not “partially” stand up in the earliest portion of the Zapruder film. It simply doesn’t happen.

Second, Hickey didn’t write in his report that he thought a firecracker exploded on the ground to the left of the motorcade as Holland and Scearce themselves acknowledge in the very next paragraph of their article: “Hickey wrote not that he bent over to his left and looked at the ground, but that he ‘stood up and looked to [his] right and rear in an attempt to identify’ the source of the loud report.” [18H762, 765 CE1024]

And we know agent Hickey is not referring to the earliest portion of the Zapruder film in his report, as Holland and Scearce claim, but in the latter portion. Why? Because we see him doing what he described in the latter portion of the film.

At Zapruder frame Z193, we see agent Hickey, who is looking to his left, snap his head toward President Kennedy and begin to rise up out of his seat until he disappears into the margins of the film at Z208. (See Figure 4) By the time James Altgens snaps his photograph at the equivalent of Zapruder frame Z255 – nearly two seconds after the second shot – Hickey is looking to his right-rear, just as he described in his report.

How do Holland and Scearce explain the divergence between what Hickey wrote and what they imagine him doing? The difference “clearly is an artifact” of what Hickey learned about the official source of the shots, Holland and Scearce tell us.

In essence, Holland and Scearce believe that Hickey mixed up his reaction to the first shot, with his reaction to the second shot, just as they believe agent Ready had. Oh yes, clearly.

Elsie Dorman Reacts

The second piece of compelling evidence that Holland and Scearce offer in support of their early shot theory is the twenty year-old recollections of Elsie Dorman who told Sixth Floor Museum curator Gary Mack in the early 1980’s that she remembered that the first shot was very loud, sounded like it came from behind her (i.e., from inside the building), and that she stopped filming just after the first shot.

Elsie Dorman, who died in 1983, had filmed the motorcade from a fourth floor window of the Depository.

Holland and Scearce cite my work on the synchronization of amateur films of the Kennedy motorcade (Epipolar Geometric Analysis of Amateur Films Related to Acoustics Evidence in the John F. Kennedy Assassination) as supportive of their theory, noting that Dorman stopped her camera three times at the time of the shooting – first at a point 0.12 seconds before Zapruder began filming the limousine (i.e., Z133); a second time at the equivalent of Z228, just after the second shot; and a third and final time at the equivalent of Z411, about five seconds after the last shot.

Holland and Scearce declare that “If Elsie Dorman’s recollection from the early 1980’s is judged to be correct, Myers’s synchronization alone corroborates that Dorman heard and reacted, as she claimed, to a first shot that occurred before Zapruder restarted his camera.”

Of course, my synchronization work only establishes the relationship between the various amateur films made of the Kennedy motorcade in Dealey Plaza – not the timing of the shots or whether Elsie Dorman’s recollection is accurate.

If Holland and Scearce really thought Dorman’s recollection was strong evidence of an early shot they probably would have led their article with it. They didn’t and the reason is clear: acceptance of this “proof” hinges on accepting Dorman’s twenty year-old recollection which isn’t quite as rock solid as they’d like us to believe.

According to Gary Mack, Dorman told him that she stopped filming after the first shot. Yet her film shows that she didn’t stop filming until after the last shot. Holland and Scearce presume that Dorman was referring to the brief break in her film at about the time Zapruder began filming the limousine gliding down Elm Street, which is convenient since that interpretation would fit their theory.

But the fact is Dorman stopped her camera three times (restarting twice) in the final moments of her film. Which camera stop did she mean coincided with the first shot? The answer is not clear, certainly not as clear as Holland and Scearce wish.

Another one of the reasons Dorman’s latter recollection is questionable concerns her comment that the shots sounded like it came from behind her (i.e., from inside the Book Depository). Holland and Scearce key in on this point, noting that “this important detail” dovetails with their own belief that an early shot “would have meant that more of the rifle’s muzzle was inside the TSBD, making the sound that much louder inside the building…”

But, Holland and Scearce must know that Elsie Dorman told the FBI the day after the assassination that the shots seemed to come from the Records Building, located diagonally across the street from her – not behind her. How inconvenient.

Towner Film Evidence

The third piece of compelling evidence that Holland and Scearce offer in support of their early shot theory is the amateur film made by Tina Towner.

Towner was the only person to capture an unbroken record of the presidential limousine turning onto Elm Street and since my 2007 Epipolar Geometric Analysis report established that the Towner film synchronized to the period immediately before Zapruder began filming, Holland and Scearce hoped that it might contain visual confirmation of their theory. The way Holland and Scearce tell it, it does.

Never mind that Tina Towner is on record as saying she heard three shots fired after she stopped filming. When it comes to inconvenient facts, Holland and Scearce simply dismiss them with the wave of a hand, in this case writing, “It should be clear that statements by filmmakers about when the shots were fired must be weighed and evaluated like all other testimony, and are not to be taken at face value.”

What gives? Only a page earlier, Holland and Scearce had embraced the two decade old recollections of amateur filmmaker Elsie Dorman, despite the fact that her latter recollection contradicted her contemporary statements about the source of the shots and failed to clarify when the first shot was fired, both central to their thesis.

Holland and Scearce go on to tell us that, truth be told; there is no reason to give Towner’s recollection any more weight than Elsie Dorman’s. It’s pretty clear, however, that they prefer Mrs. Dorman’s memory over Towner’s and equally clear that the reason is because Dorman’s recollection fits their theory. But what’s important, according to Holland and Scearce, is not the recollections of the filmmakers but what their cameras recorded.

Here, Holland and Scearce claim that the statements of three eyewitnesses – Patricia Ann Lawrence, Bonnie Ray Williams, and Harold Norman – are supported by the Towner film and serve as even more compelling evidence of an early shot.

Patricia Ann Lawrence told investigators that she was standing along the north curb of Elm Street right in front of the Depository, about seven feet west of the corner, when the motorcade came by. Holland and Scearce tell us that when the president rounded the corner, Ms. Lawrence waved at him and as he raised his hand in acknowledgement she heard the first shot.

How does Towner’s film confirm Ms. Lawrence’s account? Holland and Scearce say that the Towner film shows the president waving in Ms. Lawrence’s direction, just as she recalled.

Figure 5. Towner frame showing the presidential limousine just after it passed the traffic light pole and corresponding to Ms. Lawrence’s account, according to Holland and Scearce.

First of all, anyone familiar with the Towner film knows that the president can be seen waving more than once. Holland and Scearce acknowledge this fact, noting that the film could be cited to corroborate a first shot at various points. They just happen to favor the particular wave the president made shortly after the limousine passed under a traffic light pole for an obvious reason – it synchronizes with their early shot theory.

Never mind too that the wave selected by Holland and Scearce is long after the limousine passed Ms. Lawrence’s position in front of the Depository building.

Secondly, Ms Lawrence told the FBI in 1964 something a little different than what Holland and Scearce report. In her most extensive contemporary statement, Ms. Lawrence said “that when the car in which the President was riding passed my position I was looking at Mrs. Kennedy who was looking to the other side of the car. President Kennedy was looking in my direction and I waved. A few seconds following this I heard a shot…” [22H660 CE1381]

A few seconds? If Ms. Lawrence heard a shot a few seconds after the president waved (and not simultaneously with his wave, as Holland and Scearce report) she’d be referring to a time period synchronous with the earliest moments of the Zapruder film – not the time period when Tina Towner’s camera was still recording.

Holland and Scearce claim that two other eyewitness accounts dovetail perfectly with that of Ms. Lawrence. According to Holland and Scearce, “the same correspondence between the president’s arm motion and the first shot was also noticed” by Bonnie Ray Williams and Harold Norman, two eyewitnesses looking out the windows on the fifth floor immediately below Oswald’s sniper perch.

The “arm motion” that Holland and Scearce refer to is not the wave described by Ms. Lawrence but one of the periodic moments when the president brushed his hair back. Both Williams and Norman stated that after the president’s limousine had passed their window they saw him brushed his hair back and then they heard the first shot.

The Towner film, however, shows the president waving to the crowd to his right; not brushing his hair back as he passed the area of the building occupied by Williams and Norman. (See Figure 5) Three seconds later the Zapruder film begins and we see the president brushing his hair back, just as Williams and Norman described.

Figure 6. Towner frame showing Kennedy passing the area of the building occupied by Williams and Norman, who are five floors above the president’s limousine.

What do Holland and Scearce say? In their version of events, the president’s wave (as observed by Ms. Lawrence) and his habit of brushing his hair back (as observed by Williams and Norman) are a single event.

Holland and Scearce even go so far as to claim that a color slide taken by Phillip Willis represents the same “arm motion” seen in the Towner film and described by Lawrence, Williams, and Norman.

The Willis slide, however, was taken at the equivalent of Zapruder frame Z137, two seconds after the “arm motion” captured by Towner’s camera; the same arm motion that Holland and Scearce believe synchronizes with Ms. Lawrence’s statement and marks an early first shot.

Figure 7. Willis slide (left) and Zapruder frame Z137 (right).

If anything the Willis slide and corresponding Zapruder film sequence (showing the president brushing his hair back) are vivid illustrations of the testimony of Bonnie Ray Williams and Harold Norman and serve as strong support for the belief that the first shot was fired after Zapruder began filming, not before as Holland and Scearce theorize.

The Expended Cartridges

The fourth piece of compelling evidence that Holland and Scearce offer in support of their early shot theory is perhaps the most inventive – and silliest – of the bunch.

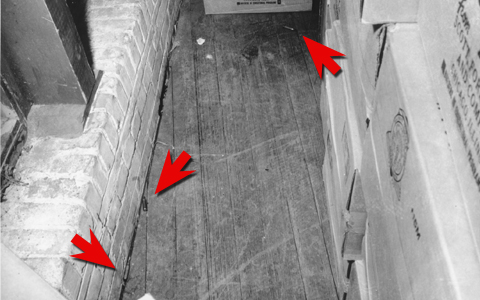

According to Holland and Scearce, the three expended cartridges found under the sixth floor window sill – two grouped together and one a short distance away – are more than just evidence of Oswald’s terrible deed, they are evidence of the angles and timing of the shots themselves.

Figure 8. Dallas police crime lab photograph of three expended shells (arrows) found under the sixth floor sniper’s nest window.

Holland and Scearce assure us that an ejected casing from an early first shot would not have ricocheted off the book cartons stacked to Oswald’s right. In all likelihood, it would have bounced and rolled unimpeded on the floor until it came to rest at the far end of the window sill. But Oswald’s next two shots would have bounced off these same cartons and ended up together against the south wall, just as they were found.

What evidence or test do Holland and Scearce offer to support their contention? Nothing, nada, zip.

To add an air of legitimacy to their baseless conjecture, Holland and Scearce bring up the testimony of Deputy Sheriff Luke Mooney who discovered the sniper’s nest and who later testified to the Warren Commission.

While marking a photograph of the sniper’s nest for the commission, Mooney made the remark, “I assume that this possibly could have been the first shot.” Warren Commission counsel Joseph Ball immediately interjected, “You cannot speculate about that.” Mooney didn’t explain further.

Holland telephoned Mooney in the hopes he might remember what he was going to tell Ball 44 years ago. Not surprisingly, Mooney was unable to recall what he meant to say.

No problem. Holland and Scearce simply testified for Mooney, writing, “A reasonable inference, if not the only one possible is that he was going to suggest that the shell identified as ‘C’ in the photograph had not bounced off the cartons of books visible on the right side of the picture. That was why it landed much further west than the two other cartridges ejected from Oswald’s rifle.”

Wow. Maybe it’s just me, but it seems pretty lame to invent “testimony” that amounts to little more than a self-serving affirmation of one’s own theory.

Holland and Scearce go on to assure us that while the pattern of expended shells is not at all dispositive, “it is suggestive and corroborative, akin to a visual equivalent of the aural pattern the majority of Dealey Plaza witnesses heard.”

What Holland and Scearce are suggesting here is that the two empty shells casings lying close together and the one further away correspond to their theory that an early first shot was followed by two more bunched close together – just as many of the ear witnesses recalled.

But as we demonstrated in the last rebuttal, placing the first shot before Zapruder began filming doesn’t produce a three shot sequence with the last two bunched together at all. It produces what sounds like an evenly spaced sequence. In fact, Holland and Scearce have yet to address an audio recreation of their shot sequence which illustrates this very point.

Furthermore, while the three expended shells scattered below the sniper’s nest window obviously support the majority of ear witnesses who heard three shots fired, Holland and Scearce haven’t provided one scintilla of evidentiary justification for their claims that the sequence and timing of those three shots would have produced the particular pattern of scattered shells later discovered by police.

I think Joseph Ball had it right, “You cannot speculate about that.”

As a final thought, Holland and Scearce offer the testimony of Garland Slack, who told sheriff deputies on the afternoon of the shooting that the first shot “sounded to me like this shot came from way back or from within a building. I have heard this same sort of sound when a shot has come from within a cave, as I have been on many big game hunts.”

Holland and Scearce insist that Slack’s statement “compliments the logical inference” that can be drawn from the pattern of shell casings under the sixth floor window – i.e., an earlier shot by Oswald would have required a steeper angle, and because of the mounted scope would have necessitated keeping more of the barrel inside the building.

Of course, what they don’t say (and possibly don’t realize) is that none of the evidence offered would have changed dramatically had Oswald fired a first shot a few seconds after Zapruder began filming as practically everyone has believed for more than four decades – the angle to the street would have been essentially the same, the muzzle would still have been predominately inside of the building, and the shells would have kicked out of the chamber at nearly the same interval and angle.

Cherry-Picking History

At the tail of their essay, Holland and Scearce assure us that “even more evidence exists that corroborates or dovetails” with their theory (which they promise to deliver in even more future installments), but due to the passage of time no single test or proof can settle the idea of an earlier shot one way or the other.

No matter, Holland and Scearce assure us that their early shot theory is “already in accordance with more of the facts than any other theory of what happened.”

It’s hard to imagine a statement less true and more self-serving given the amount of hoop-jumping necessary to dredge up “evidence” that supports their theory.

Early on in their essay, Holland and Scearce wrote that “It’s easy to foresee the objections that will be made against the foregoing analysis. The charge of ‘cherry-picking’ eyewitness testimony is bound to be raised, either in the sense that conflicting accounts were ignored, or that the recollections of Ready, Bennett and Hickey were used selectively and even distorted.” Yea, no kidding.

So, how do Holland and Scearce defend their cherry-picking approach to history? Incredibly, they write that the judicious cherry-picking of eyewitness statements is not just unavoidable, it is “precisely what must be done.”

It’s an audacious statement and one that I couldn’t disagree with more. While no historic rendering can ever include every detail on record, we expect those who profess to be historians to make sense of it all by painting an honest, accurate, balanced portrait of human events. Anything less is an incredible disservice to future generations.

The historic record of the Kennedy assassination has been needlessly muddied with more than four decades of irresponsible nonsense. What the world craves now is clarity, not more mud.

Yet rather than working to clarify the record, Max Holland and pal Kenneth Scearce seem more focused on convincing everyone that their theory is a scholarly work of historic significance. Truth is this is the third attempt to sell us on the merits of their case and the thinnest of the three.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s not hard to imagine that Oswald might have fired a first shot earlier than anyone had ever considered before. It’s just that no one has yet uncovered any believable, cohesive evidence that it actually happened, despite bushels of judicious cherry pickin’.

Flash 8 or higher is required to view videos accompanying this article. Get the free plugin now.

In February, 2007, author Max Holland and Johann W. Rush posited that Lee Harvey Oswald fired his first shot earlier than anyone had ever suspected – before the famous Zapruder film even began churning through old Abe’s 8mm Bell & Howell camera.

After evidence for their theory was examined and debunked by these authors in Max Holland’s 11 Seconds in Dallas, Seattle attorney and assassination student Kenneth R. Scearce fired back with an independent article aimed at finding fault with our rebuttal and support for Holland’s so-far, unsupportable theory.

Again, Holland’s early shot theory and Scearce’s challenge were debunked in a second article titled, Holland Déjà Vu.

Apparently, Misters Holland and Scearce haven’t had enough. They’re back, this time in a joint effort titled: 11 Seconds in Dallas Redux: Filmed Evidence, which promises readers that several pieces of old evidence turn out to corroborate the suspected early shot after all and that Holland’s theory “should now be regarded as the depiction with the greatest fidelity to all the known facts.”

If it all sounds too good to be true, you’re right; especially when one begins examining the old evidence that Holland and Scearce find so compelling that we’re expected to chuck forty-five years of research into the shooting sequence right out the sixth floor window.

Instead of impressive fact-finding, Holland and Scearce treat readers to a hodge-podge of assumptions, elastic reasoning, and twisted truth – par for the course, I’m afraid, in every attempt to sell this fantasy so far.

I’ll give Holland and Scearce this much, they’re open and honest about cherry-picking the facts to build a case for their theory. More on that later.

Twenty months after first publishing their theory, and in the wake of two thorough rebuttals which pointed out the fallacy of their claims, Holland and Scearce finally decided to take “a fresh look” at all the amateur films made of the president’s limousine in Dealey Plaza and test them against their own hypothesis.

It seems a little odd to be testing one’s hypothesis after one has announced to the world that the history books should be rewritten, but maybe that’s just me.

According to Holland and Scearce, it’s all okay because the recent testing phase has “unearthed some compelling corroboration” for their early shot theory.

So, what is the earth shattering evidence that has escaped the scrutiny of everyone who has ever examined the shooting sequence so far? The evidence amounts to these four points:

- The Zapruder film shows three Secret Service agents reacting “in an unusual manner” by frame Z153;

- Amateur filmmaker Elsie Dorman reacted to a first shot before Zapruder began filming the presidential limousine (i.e., before Z133);

- Tina Towner’s amateur film corroborates the testimony of several eyewitnesses who say the first shot was fired as the president waved to the crowd immediately after turning onto Elm Street; a moment that could only have been before Zapruder began filming the president (i.e., before Z133); and

- The pattern of empty cartridge shells found under the sixth floor window is “suggestive and corroborative” of an early first shot.

Three Agents

First, Holland and Scearce wrote that “there can be no question” that Secret Service agents John D. Ready, Glen A. Bennett, and George W. Hickey, Jr., were reacting to “a worrisome stimulus” by Zapruder frame Z153.

Why are Holland and Scearce so certain on this point? Because, according to Secret Service protocol, agents assigned to the right side of the presidential follow-up car (like Ready) are supposed to keep their eyes fixed on the area to the right of the car; those of the left toward the left side of the car.

Thus, according to Holland and Scearce, the fact that agent Ready was looking to his left (not his right, per protocol) at frame Z153 could only mean that he was responding to “some kind of stimulus” – translation: he heard a shot.

Really? Does that mean that anytime an agent breaks protocol it can only mean that he is responding to a shot? If that were true, then frames M446-M456 of the Marie Muchmore film would be evidence of a shot being fired as the presidential limousine moved up Houston Street since it shows agent Paul Landis, who is standing on the right running board behind agent Ready, looking to his left instead of his right protocol position.

|

Isn’t it reasonable that agents aboard the Secret Service follow-up car broke protocol on multiple occasions (if only very briefly) throughout the motorcade’s 39-minute journey through Dallas? And doesn’t that mean that we can’t read too much into agent Ready’s brief leftward glance at the head of the Zapruder film? Or are Holland and Scearce the only ones who can divinely separate those Secret Service agent reactions that correspond to shots and those that don’t?

In addition to their protocol argument, Holland and Scearce assure us that we can actually see agent Ready turn to his left at Zapruder frame Z139, in reaction to their early shot. But can we?

The image of Secret Service agent Ready appears in the sprocket hole area of the Zapruder film between Z133 and Z154. In fact, with the exception of two frames – Z138 and Z139 – agent Ready’s head is not even visible, being obscured by the sprocket hole. It isn’t until frames Z153-154 that we can actually see Ready looking to his left.

So, what about the head turn? There are only two frames – Z138 and Z139 – that suggest that Ready might be turning his head from right to left. I say “might” because we can only see a third of the left side of Ready’s head for one-tenth of a second and even then the image is unduly affected by film artifacts because of its close proximity to the sprocket hole. Suffice it to say, this is hardly the kind of definitive evidence you can take to the bank.

But let’s assume for sake of argument that the film does show Ready turning to his left at about frame Z139, as Holland and Scearce claim. What does the rest of the film reveal? At about Z164, Ready turned to face forward again, then at Z177 snapped his head to the right, and by Z255 had turned sharply to his right-rear (as seen in a photograph by James Altgens).

|

These filmed actions are consistent with Ready’s contemporary reports. A few days after the assassination, Ready wrote a detailed account of his actions in which he said that upon hearing what he thought were firecrackers “immediately turned to my right rear trying to locate the source.” [18H749 CE1024]

How do Holland and Scearce deal with this contemporary report? They dismiss it, suggesting that Ready’s report was written to conform to the official version of events, having been written after Ready had learned that all three shots had come from Oswald’s perch in the Book Depository.

Holland and Scearce don’t offer any actual evidence (written or otherwise) to support their belief that Ready fudged the truth in his after-action report or why he would even need to hide the fact that he might have looked left instead of right after hearing the first shot. It would appear that it’s simply better for their theory if Ready forgot to mention that initial left turn. How convenient.

The way Holland and Scearce see it, Ready did turn to his right-rear, as he later reported, but only after the second shot, at around Z223. In a footnote, the theorists acknowledge that they don’t really know if Ready turned to his right-rear after the second shot since he disappeared from the Zapruder film a moment earlier, at frame Z208, but thought it unlikely that Ready would have looked back between Z208 and 223. Of course, if the Zapruder film had shown Ready looking back before Z223 their theory would be kaput.

In the end, the image Holland and Scearce paint is one in which agent Ready reacts to an early shot by turning to his left, returns his gaze to the right (his protocol position), then suddenly snaps his head toward the right-rear after hearing the second shot. Later, Ready writes a report that ignores his left-turn reaction to the first shot in order to better fit the Oswald-did-it theory. Yea, sure.

Holland and Scearce’s vision of history is not only a stretch; it’s a bit disingenuous given the filmed record.

The Zapruder film shows agent Ready making a sweeping turn to his right beginning at Z177 and continuing until he disappears into the margins of the film at Z208. (See Figure 4) By then, Ready is looking to his right at a 40 degree angle relative to the midline of the car. Two and one-half seconds later (Z255), Ready had turned another 120-degrees further rearward (as evidenced by the James Altgens photograph). All of this is precisely what Ready described in his after-action report and places the time of the first shot a second or so before Z177. What is so mysterious?

According to Holland and Scearce, the actions of two other agents – Glen Bennett and George Hickey – support their early shot thesis and corroborate their interpretation of agent Ready’s actions.

Agents Glen Bennett and George Hickey were both seated in the back seat of the Secret Service follow-up car – Bennett on the passenger-side and Hickey on the driver-side.

Bennett wrote, “I immediately, upon hearing the supposed firecracker, looked at the boss’s car. At this exact time I saw a shot that hit the boss about four inches down from the right shoulder; a second shot followed immediately and hit the right rear high of the boss’s head.” [18H760 CE1024]

Holland and Scearce spend time telling us about how “remarkably accurate and succinct” Bennett’s statement is and how they, and they alone, noticed something that no one ever recognized before – Bennett mentioned looking at the president immediately after the first shot.

Turning to the Zapruder film, Holland and Scearce claim that by Zapruder frame Z153, Bennett “had turned his eyes toward the front and tilted his head markedly to the right so he could keep his eye on ‘the boss’;” presumably so he could see around the two front passengers seated in front of him. Holland and Scearce assert that Bennett’s head tilt occurs simultaneously with agent Ready’s left head turn at Z139 and as such is clear, corroborative evidence of an earlier shot.

Really? Let’s back up a minute. First, how in the devil are Holland and Scearce able to see Bennett “turn his eyes” toward the front of the car – or in any direction for that matter – during these earliest Zapruder frame sequences? One can’t even distinguish Bennett’s eyes from his nose in these early, fuzzy frames, let alone determine in which direction he’s looking. (See Figure 2) Even Holland and Scearce acknowledge later in their article, “The film’s resolution simply isn’t sufficient to discern any reflexive responses that probably occurred in reaction to the first, missed shot.”

Second, and of paramount importance, is a fact Holland and Scearce seem to forget in their zeal to break “new” ground – Bennett described how he looked at the president immediately after the first shot and “at this exact time” saw him hit in the back with the second shot.

Doesn’t that mean that Bennett’s remarkably accurate and succinct report was conveying how Bennett turned and looked at the president immediately before the second shot (the shot to Kennedy’s back at about Z223), and not four and one-half seconds earlier. The reason that we can’t ascertain exactly what Bennett did during those four and one-half seconds is because he is hidden from Zapruder’s camera view by Z165. How convenient for Holland and Scearce’s theory.

If the admittedly subtle actions of agents Ready and Bennett don’t convince you of an earlier shot, Holland and Scearce insist, then you’ll certainly be won over by the actions of agent George Hickey, whose movements “cannot be characterized as anything but extraordinary.”

Holland and Scearce assure us that beginning at Z139 agent Hickey can be seen “partially standing up” and by Z153 “beginning to lean way over the driver’s side” of the follow-up car, “almost as if he were looking for something on the ground.” Holland and Scearce believe he was looking for something at ground level, writing, “According to his later statement, Hickey said he thought the initial loud report was a firecracker, and that it exploded at ground level.”

Wait just a moment. First, agent Hickey does not “partially” stand up in the earliest portion of the Zapruder film. It simply doesn’t happen.

Second, Hickey didn’t write in his report that he thought a firecracker exploded on the ground to the left of the motorcade as Holland and Scearce themselves acknowledge in the very next paragraph of their article: “Hickey wrote not that he bent over to his left and looked at the ground, but that he ‘stood up and looked to [his] right and rear in an attempt to identify’ the source of the loud report.” [18H762, 765 CE1024]

And we know agent Hickey is not referring to the earliest portion of the Zapruder film in his report, as Holland and Scearce claim, but in the latter portion. Why? Because we see him doing what he described in the latter portion of the film.

At Zapruder frame Z193, we see agent Hickey, who is looking to his left, snap his head toward President Kennedy and begin to rise up out of his seat until he disappears into the margins of the film at Z208. (See Figure 4) By the time James Altgens snaps his photograph at the equivalent of Zapruder frame Z255 – nearly two seconds after the second shot – Hickey is looking to his right-rear, just as he described in his report.

How do Holland and Scearce explain the divergence between what Hickey wrote and what they imagine him doing? The difference “clearly is an artifact” of what Hickey learned about the official source of the shots, Holland and Scearce tell us.

In essence, Holland and Scearce believe that Hickey mixed up his reaction to the first shot, with his reaction to the second shot, just as they believe agent Ready had. Oh yes, clearly.

Elsie Dorman Reacts

The second piece of compelling evidence that Holland and Scearce offer in support of their early shot theory is the twenty year-old recollections of Elsie Dorman who told Sixth Floor Museum curator Gary Mack in the early 1980’s that she remembered that the first shot was very loud, sounded like it came from behind her (i.e., from inside the building), and that she stopped filming just after the first shot.

Elsie Dorman, who died in 1983, had filmed the motorcade from a fourth floor window of the Depository.

Holland and Scearce cite my work on the synchronization of amateur films of the Kennedy motorcade (Epipolar Geometric Analysis of Amateur Films Related to Acoustics Evidence in the John F. Kennedy Assassination) as supportive of their theory, noting that Dorman stopped her camera three times at the time of the shooting – first at a point 0.12 seconds before Zapruder began filming the limousine (i.e., Z133); a second time at the equivalent of Z228, just after the second shot; and a third and final time at the equivalent of Z411, about five seconds after the last shot.

Holland and Scearce declare that “If Elsie Dorman’s recollection from the early 1980’s is judged to be correct, Myers’s synchronization alone corroborates that Dorman heard and reacted, as she claimed, to a first shot that occurred before Zapruder restarted his camera.”

Of course, my synchronization work only establishes the relationship between the various amateur films made of the Kennedy motorcade in Dealey Plaza – not the timing of the shots or whether Elsie Dorman’s recollection is accurate.

If Holland and Scearce really thought Dorman’s recollection was strong evidence of an early shot they probably would have led their article with it. They didn’t and the reason is clear: acceptance of this “proof” hinges on accepting Dorman’s twenty year-old recollection which isn’t quite as rock solid as they’d like us to believe.

According to Gary Mack, Dorman told him that she stopped filming after the first shot. Yet her film shows that she didn’t stop filming until after the last shot. Holland and Scearce presume that Dorman was referring to the brief break in her film at about the time Zapruder began filming the limousine gliding down Elm Street, which is convenient since that interpretation would fit their theory.

But the fact is Dorman stopped her camera three times (restarting twice) in the final moments of her film. Which camera stop did she mean coincided with the first shot? The answer is not clear, certainly not as clear as Holland and Scearce wish.

Another one of the reasons Dorman’s latter recollection is questionable concerns her comment that the shots sounded like it came from behind her (i.e., from inside the Book Depository). Holland and Scearce key in on this point, noting that “this important detail” dovetails with their own belief that an early shot “would have meant that more of the rifle’s muzzle was inside the TSBD, making the sound that much louder inside the building…”

But, Holland and Scearce must know that Elsie Dorman told the FBI the day after the assassination that the shots seemed to come from the Records Building, located diagonally across the street from her – not behind her. How inconvenient.

Towner Film Evidence

The third piece of compelling evidence that Holland and Scearce offer in support of their early shot theory is the amateur film made by Tina Towner.

Towner was the only person to capture an unbroken record of the presidential limousine turning onto Elm Street and since my 2007 Epipolar Geometric Analysis report established that the Towner film synchronized to the period immediately before Zapruder began filming, Holland and Scearce hoped that it might contain visual confirmation of their theory. The way Holland and Scearce tell it, it does.

Never mind that Tina Towner is on record as saying she heard three shots fired after she stopped filming. When it comes to inconvenient facts, Holland and Scearce simply dismiss them with the wave of a hand, in this case writing, “It should be clear that statements by filmmakers about when the shots were fired must be weighed and evaluated like all other testimony, and are not to be taken at face value.”

What gives? Only a page earlier, Holland and Scearce had embraced the two decade old recollections of amateur filmmaker Elsie Dorman, despite the fact that her latter recollection contradicted her contemporary statements about the source of the shots and failed to clarify when the first shot was fired, both central to their thesis.

Holland and Scearce go on to tell us that, truth be told; there is no reason to give Towner’s recollection any more weight than Elsie Dorman’s. It’s pretty clear, however, that they prefer Mrs. Dorman’s memory over Towner’s and equally clear that the reason is because Dorman’s recollection fits their theory. But what’s important, according to Holland and Scearce, is not the recollections of the filmmakers but what their cameras recorded.

Here, Holland and Scearce claim that the statements of three eyewitnesses – Patricia Ann Lawrence, Bonnie Ray Williams, and Harold Norman – are supported by the Towner film and serve as even more compelling evidence of an early shot.

Patricia Ann Lawrence told investigators that she was standing along the north curb of Elm Street right in front of the Depository, about seven feet west of the corner, when the motorcade came by. Holland and Scearce tell us that when the president rounded the corner, Ms. Lawrence waved at him and as he raised his hand in acknowledgement she heard the first shot.

How does Towner’s film confirm Ms. Lawrence’s account? Holland and Scearce say that the Towner film shows the president waving in Ms. Lawrence’s direction, just as she recalled.

|

First of all, anyone familiar with the Towner film knows that the president can be seen waving more than once. Holland and Scearce acknowledge this fact, noting that the film could be cited to corroborate a first shot at various points. They just happen to favor the particular wave the president made shortly after the limousine passed under a traffic light pole for an obvious reason – it synchronizes with their early shot theory.

Never mind too that the wave selected by Holland and Scearce is long after the limousine passed Ms. Lawrence’s position in front of the Depository building.

Secondly, Ms Lawrence told the FBI in 1964 something a little different than what Holland and Scearce report. In her most extensive contemporary statement, Ms. Lawrence said “that when the car in which the President was riding passed my position I was looking at Mrs. Kennedy who was looking to the other side of the car. President Kennedy was looking in my direction and I waved. A few seconds following this I heard a shot…” [22H660 CE1381]

A few seconds? If Ms. Lawrence heard a shot a few seconds after the president waved (and not simultaneously with his wave, as Holland and Scearce report) she’d be referring to a time period synchronous with the earliest moments of the Zapruder film – not the time period when Tina Towner’s camera was still recording.

Holland and Scearce claim that two other eyewitness accounts dovetail perfectly with that of Ms. Lawrence. According to Holland and Scearce, “the same correspondence between the president’s arm motion and the first shot was also noticed” by Bonnie Ray Williams and Harold Norman, two eyewitnesses looking out the windows on the fifth floor immediately below Oswald’s sniper perch.

The “arm motion” that Holland and Scearce refer to is not the wave described by Ms. Lawrence but one of the periodic moments when the president brushed his hair back. Both Williams and Norman stated that after the president’s limousine had passed their window they saw him brushed his hair back and then they heard the first shot.

The Towner film, however, shows the president waving to the crowd to his right; not brushing his hair back as he passed the area of the building occupied by Williams and Norman. (See Figure 5) Three seconds later the Zapruder film begins and we see the president brushing his hair back, just as Williams and Norman described.

|

What do Holland and Scearce say? In their version of events, the president’s wave (as observed by Ms. Lawrence) and his habit of brushing his hair back (as observed by Williams and Norman) are a single event.

Holland and Scearce even go so far as to claim that a color slide taken by Phillip Willis represents the same “arm motion” seen in the Towner film and described by Lawrence, Williams, and Norman.

The Willis slide, however, was taken at the equivalent of Zapruder frame Z137, two seconds after the “arm motion” captured by Towner’s camera; the same arm motion that Holland and Scearce believe synchronizes with Ms. Lawrence’s statement and marks an early first shot.

|

If anything the Willis slide and corresponding Zapruder film sequence (showing the president brushing his hair back) are vivid illustrations of the testimony of Bonnie Ray Williams and Harold Norman and serve as strong support for the belief that the first shot was fired after Zapruder began filming, not before as Holland and Scearce theorize.

The Expended Cartridges

The fourth piece of compelling evidence that Holland and Scearce offer in support of their early shot theory is perhaps the most inventive – and silliest – of the bunch.

According to Holland and Scearce, the three expended cartridges found under the sixth floor window sill – two grouped together and one a short distance away – are more than just evidence of Oswald’s terrible deed, they are evidence of the angles and timing of the shots themselves.

|

Holland and Scearce assure us that an ejected casing from an early first shot would not have ricocheted off the book cartons stacked to Oswald’s right. In all likelihood, it would have bounced and rolled unimpeded on the floor until it came to rest at the far end of the window sill. But Oswald’s next two shots would have bounced off these same cartons and ended up together against the south wall, just as they were found.

What evidence or test do Holland and Scearce offer to support their contention? Nothing, nada, zip.

To add an air of legitimacy to their baseless conjecture, Holland and Scearce bring up the testimony of Deputy Sheriff Luke Mooney who discovered the sniper’s nest and who later testified to the Warren Commission.

While marking a photograph of the sniper’s nest for the commission, Mooney made the remark, “I assume that this possibly could have been the first shot.” Warren Commission counsel Joseph Ball immediately interjected, “You cannot speculate about that.” Mooney didn’t explain further.

Holland telephoned Mooney in the hopes he might remember what he was going to tell Ball 44 years ago. Not surprisingly, Mooney was unable to recall what he meant to say.

No problem. Holland and Scearce simply testified for Mooney, writing, “A reasonable inference, if not the only one possible is that he was going to suggest that the shell identified as ‘C’ in the photograph had not bounced off the cartons of books visible on the right side of the picture. That was why it landed much further west than the two other cartridges ejected from Oswald’s rifle.”

Wow. Maybe it’s just me, but it seems pretty lame to invent “testimony” that amounts to little more than a self-serving affirmation of one’s own theory.

Holland and Scearce go on to assure us that while the pattern of expended shells is not at all dispositive, “it is suggestive and corroborative, akin to a visual equivalent of the aural pattern the majority of Dealey Plaza witnesses heard.”

What Holland and Scearce are suggesting here is that the two empty shells casings lying close together and the one further away correspond to their theory that an early first shot was followed by two more bunched close together – just as many of the ear witnesses recalled.

But as we demonstrated in the last rebuttal, placing the first shot before Zapruder began filming doesn’t produce a three shot sequence with the last two bunched together at all. It produces what sounds like an evenly spaced sequence. In fact, Holland and Scearce have yet to address an audio recreation of their shot sequence which illustrates this very point.

Furthermore, while the three expended shells scattered below the sniper’s nest window obviously support the majority of ear witnesses who heard three shots fired, Holland and Scearce haven’t provided one scintilla of evidentiary justification for their claims that the sequence and timing of those three shots would have produced the particular pattern of scattered shells later discovered by police.

I think Joseph Ball had it right, “You cannot speculate about that.”

As a final thought, Holland and Scearce offer the testimony of Garland Slack, who told sheriff deputies on the afternoon of the shooting that the first shot “sounded to me like this shot came from way back or from within a building. I have heard this same sort of sound when a shot has come from within a cave, as I have been on many big game hunts.”

Holland and Scearce insist that Slack’s statement “compliments the logical inference” that can be drawn from the pattern of shell casings under the sixth floor window – i.e., an earlier shot by Oswald would have required a steeper angle, and because of the mounted scope would have necessitated keeping more of the barrel inside the building.

Of course, what they don’t say (and possibly don’t realize) is that none of the evidence offered would have changed dramatically had Oswald fired a first shot a few seconds after Zapruder began filming as practically everyone has believed for more than four decades – the angle to the street would have been essentially the same, the muzzle would still have been predominately inside of the building, and the shells would have kicked out of the chamber at nearly the same interval and angle.

Cherry-Picking History

At the tail of their essay, Holland and Scearce assure us that “even more evidence exists that corroborates or dovetails” with their theory (which they promise to deliver in even more future installments), but due to the passage of time no single test or proof can settle the idea of an earlier shot one way or the other.

No matter, Holland and Scearce assure us that their early shot theory is “already in accordance with more of the facts than any other theory of what happened.”

It’s hard to imagine a statement less true and more self-serving given the amount of hoop-jumping necessary to dredge up “evidence” that supports their theory.

Early on in their essay, Holland and Scearce wrote that “It’s easy to foresee the objections that will be made against the foregoing analysis. The charge of ‘cherry-picking’ eyewitness testimony is bound to be raised, either in the sense that conflicting accounts were ignored, or that the recollections of Ready, Bennett and Hickey were used selectively and even distorted.” Yea, no kidding.

So, how do Holland and Scearce defend their cherry-picking approach to history? Incredibly, they write that the judicious cherry-picking of eyewitness statements is not just unavoidable, it is “precisely what must be done.”

It’s an audacious statement and one that I couldn’t disagree with more. While no historic rendering can ever include every detail on record, we expect those who profess to be historians to make sense of it all by painting an honest, accurate, balanced portrait of human events. Anything less is an incredible disservice to future generations.

The historic record of the Kennedy assassination has been needlessly muddied with more than four decades of irresponsible nonsense. What the world craves now is clarity, not more mud.

Yet rather than working to clarify the record, Max Holland and pal Kenneth Scearce seem more focused on convincing everyone that their theory is a scholarly work of historic significance. Truth is this is the third attempt to sell us on the merits of their case and the thinnest of the three.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s not hard to imagine that Oswald might have fired a first shot earlier than anyone had ever considered before. It’s just that no one has yet uncovered any believable, cohesive evidence that it actually happened, despite bushels of judicious cherry pickin’.

18 comments:

This article is yet another well-written, thoroughly-researched piece authored by Dale K. Myers, which once again illustrates his tremendous ability to get to the facts of a particular JFK-related subject, while systematically and step-by-step stripping away the nonsense that is continually being purported by the various JFK theorists.

Nice job, Dale (once again).

Agreed.

Addendum.....

Kudos to Todd Vaughan too. He's listed as co-author of this article. I shouldn't have left him out of my comment above.

I agree with David. Dale has done us a great service by providing clear, coherent analyses of both the Tippit murder and the JFK shot sequence.

Dale and Todd: Thank you very much.

Good article, but it would have been better if it had mentioned the impossibility of a shot fired from the sixth floor before Zapruder frame 166 striking the curb near James Tague, at the west end of Dealey Plaza

I cannot think of any reason why Oswald would wait until his target was approaching 1/3 to 2/3 of a football field away before taking his first shot. It certainly makes sense that a much closer shot was desirable.

After visiting Dealey Plaza it was apparent from standing on the sixth floor looking down on Elm Street that at a steep angled shot would be necessary at or near the traffic light post. If a shot is taken at a steep angle at close range the shot would require under hold because of the bullet going higher than the point of aim.

Secondly, depending on Oswald’s sight in distance for his scope (e.g., 50 or 100 yards) the bullet would travel a parabolic arc to the point of impact and at distances closer than the sight in distance the arc would be higher (i.e., overshooting).

The ammunition for Oswald’s rifle had an initial velocity of about 2200 ft/sec which is rather slow and would require an adjustment for elevation at a short distance somewhere around 1.0 to 1.5 inches (meaning a lower hold).

The failure to correct for the steep angle and scope setting certainly could have caused Oswald to miss his first shot (aiming perhaps 2 to 3 inches to high), however, looking through his scope the cross hairs would look on target but in reality the aim point possibly could be a pole, tree limb etc.

Actually in the Zapruder film there is an almost simultaneous leftward head turn of JFK, Mrs. Kennedy, Secret Service Agent Hickey and Texas Gov. Connally visible in Zapruder frames 140 to 149. The time of this event was within ½ second of each other suggesting a common cause (i.e., gunshot).

A flinch reaction to a gunshot would be almost immediate (on the order of ¼ second); however, a reaction of ‘what just happened’ would be much longer (on the order of 2 to 3 times). If that is the case, then the first shot would be before 155 and more nearer the start of the Zapruder film.

This is what convinced me that Oswald certainly could have shot accurately 3 times in a matter of 8.0 to 11.0 seconds (instead of 3 to 4 in WC report)and away from the conspiracy theory.

Actually, an early shot would have been the most difficult because Oswald would have to track his target from left to right and at a considerably steep angle. One the many reasons why it made more sense to wait until the car was further down Elm Street when it would have been moving directly away from the sniper position. As for a first shot miss, Oswald missed the entire 21 foot limousine which means that his shot (whatever the reason for the miss) didn't have anything to do with the settings of the scope. Finally, there is no compelling Zapruder film evidence in the 133-155 range that suggests a shot earlier than Z155 - including your claim that such evidence exists in the 140-149 range. Compare all of the films and photographs taken before, during, and after your cited time range and it is clear that the actions of the principles you name are not in fact exhibiting a reaction to a severe external stimulus but merely following through with actions begun previously in response to the crowd on both sides of the street. Yes, Oswald had plenty of time to get off three shots in 8.3 seconds, however, a shot earlier than Z155 is not required to accomplish this feat, nor is there any compelling photographic, eyewitness, or physical evidence to support such a notion - which was the point of the three articles rebutting Holland's theory.

Here's an unpicked cherry: in "Whitewash," Harold Weisberg noted blurring of the Zapruder film, beginning at frame 190. He attributed it to Zapruder's reaction to a shot. The HSCA's photographic experts discovered blurring at frames 189-97 and 312-34. If you assert that a shot was fired before frame 189, as Holland does, you have to explain why Zapruder didn't react to it.

A couple of things to keep in mind: The blur analysis fails to take into account that blurs could have been caused by external stimuli other than auditory ones. In addition, Holland postulates that the first shot was fired before Zapruder began filming.

The best evidence that LHO switched direction is that he did the same thing twice later, ducking into Brewer's shop, and sneaking into the movie theater, each time drawing attention for suspicious behavior, and each time in response to a cop car driving by.

Mr. Myers,

Holland and Scearce's most publicized evidence of the first shot occurring just before Zapruder resumed filming (aside from the ricochet being the most plausible explanation for how Oswald missed a 21-foot long car) was the near simultaneous (within .5 seconds) left head turn of Kennedy, Connelly, Mrs. Kennedy, and agent Hickey in Z frames 140-149. I've seen the film and it's quite obvious that this occurred. Yet, in your blog above, you never mention this simultaneous head turn. Instead you focus on the head and body movements of the secret service agents in the trailing car. Only when "merbeau" above mentioned these head movements in 140-149 did you address it with the rather vague "following through with actions begun previously in response to the crowd on both sides of the street." Why all the detailed attention on the movements of the occupants of the trailing car and little or no attention to the Kennedy's, Connelly, and Hickey, in Z 140-149?

Anon,

This subject has been dealt in multiple articles on this blogsite. (Search: Holland) In particular, the Z140-149 head turns and my response in the comments section of the Dec. 4, 2008 article above, were addressed in considerable detail a year earlier (in the Dec. 20, 2007 article: Holland Déjà Vu). You must have missed it.

Thank you for your prompt response. Also, thank you for all of the hard work you've done to put to rest some of the ridiculous conspiracy theories that a large proportion of the American public can't seem to let go of. Please bare with me and I'll get to my question. If I understand this correctly, the Zapruder film runs at 18.3 frames per second. You (and many others) believe that the evidence suggests that Oswald took his first shot around frame 156 (155-157). Holland, Rush (and some others), believe this first shot occurred an instant before Zapruder resumed filming at frame 133. Depending on reaction time, which can only be approximated, I believe this means that the dispute is over a period of 1 to 2 seconds. Given this narrow window, and the unreliability of eye and ear witness testimony, it's understandable that each of you is able to cite examples of testimony that seem to support your claim. Sometimes, both sides even cite the same testimony, combined with still photographs and film clips, as evidence that the other is wrong. I think it would be fair to say that this will never be resolved using witness testimony. Each of you can also cite frames and sequences in the Zapruder film that seem to support your claim so, again, nothing definitive that I can see. Holland et. al examined the actual traffic mast and acknowledged that they didn't find anything (other than a rust spot) that was evidence of a bullet ricochet. Given the passage of time (rusting and painting) this neither proves that it did or didn't happen. They also did some ballistics testing which seemed to me to be inconclusive. Taken in sum, I would say that neither the 156 nor the pre-133 group can definitively prove its point based on testimony, photographs, or films. This brings me, finally, to my question. Oswald delivered two devastatingly accurate shots (2 and 3) at the presidents upper back and head at long range, but at short range, he missed the broadside of a 21-foot long limousine as it traveled right past him from left to right. I've never fired a gun, but these facts are very difficult to reconcile. To have missed Kennedy, maybe, but the entire car? Given the location of the limousine at frame 156, is it possible to estimate the minimum displacement of the barrel from the center of Kennedy's body to produce a miss that didn't even hit the car?

Anon,

I think you've missed the point about my dissertations on Holland's theory - or any theory for that matter - that seeks to upset the proverbial apple cart without offering believable evidence to support that theory. As I have demonstrated again and again in the seven articles on this blog site, Holland has failed to offer anything that is believable (eyewitness testimony or more importantly physical evidence) to support what he claims everyone has missed. Eyewitness testimony is subjective, however, when combined with films and photographs one can reconstruct reality with a reasonable degree of certainty. Holland's efforts have been botched at best. I'm not going to argue with someone over what might have happened during a two second interval, but I will argue all day long with someone who attempts to reconstruct their own reality based on a skewed version of eyewitness testimony, photographic images, and scientific evidence. If you're going to claim to re-write history, do it using the puzzle pieces we have, not a handcrafted set of one's own making. Holland's theory offers nothing new to the assassination story and by his own admission has no physical basis in reality. Forensic ballistic experts Luke and Michael Haag have proven to my satisfaction that Holland's theorized ricochet off the mast post is impossible as speculated. They've done the real world tests and posted the results. So, it's little wonder that Holland could find no physical evidence for an impossible ricochet. As for Oswald's first shot miss, who knows? There are a million-and-one reasons why he missed. Pick one. The only thing that can be said for certain is it did miss. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

Sounds to me like the author of this article is a bit put out that Holland may have the very thing that makes any sense after all these years. Common sense alone makes a person ask, how could Oswald miss the whole car? In 50 years of my own research,. Holland's view makes more sense than anything I have heard regarding the missed shot.

A theory requires actual evidence otherwise it remains an unsubstantiated/unsupported theory, yes? In this case, as the authors have shown time and again, there is no evidence - neither testimonial nor physical - that supports Holland's theory. Even Holland himself acknowledges (after careful examination of the original mast pole) that there is no physical evidence that an errant bullet actually struck the mast pole in the manner that he theorizes. Other forensic experts (the Haag team) who have also examined the original mast pole not only agree but have made the convincing argument (backed up with scientific evidence and demonstrations) that such a theory is forensically impossible under the circumstances. The authors concur. Search "Holland" on this blog for a series of related articles.

Hi Dale,

Going from memory here, but iirc Holland found a very shallow, 2" long, covered-by-several-coats-of-paint rusty dent about 20 inches from the end of the mast arm.

Questions:

What was Agent Hickey bending over and looking at on the pavement for so many frames starting around Z-150? A firecracker? (No sarcasm intended)

Why did Agent Bennett next to him start leaning over to his right and looking around Ken O'Donnell -- to make sure JFK was okay --so early on in the film?

Why are two or three people in the crowd apparently leaning over and looking at (or searching for) whatever it is Hickey is looking at (or searching for) on the pavement?

Thanks.

Thomas - It doesn't sound like you're up to speed on this subject. Try reading this and the other articles linked within:

https://jfkfiles.blogspot.com/2015/06/hollands-deflection-ballistics-and-truth.html

As for Agents Hickey and Bennett and folks in the crowd that you claim are reacting to a shot, I wouldn't presume to know what they're thinking or where they're looking based on the Zapruder film (can you *really* see their eyes?) without interviewing them and showing them the film sequence in question. I'll leave those kind of assumptions to others.

Good luck with your search for the truth.

Post a Comment