The December issue of the American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology (Vol. 40, No. 4, pp.336-346) features an important article by respected firearms examiner and author Lucien C. “Luke” Haag that explores the unique characteristics of the ammunition used by Lee Harvey Oswald in JFK assassination and offers a clearer understanding of the ballistic principles that resulted in the president’s death.

Haag, a former Criminalist and Technical Director of the Phoenix Crime Laboratory, with over 50-years of experience in the field of criminalistics and forensic firearms examination, and author of over 200 scientific papers dealing with the effects and behavior of projectiles, brings his first-hand knowledge and testing to bear on questions surrounding the single-bullet theory and Kennedy’s fatal head wound.

The eleven-page article explains in detail why doctors and forensic examiners at the time were not in a position to understand the unique characteristics of the wound produced by the Model 91/38 Carcano rifle and the WCC 6.5mm ammunition used by Oswald – a rather uncommon weapon in 1963.

Bullet design considerations

While the general shape and design of the 6.5mm Carcano bullet are not unique; the 6.5 x 52-mm Carcano cartridge is unique to the Carcano rifle; no other firearm is chambered for this cartridge.

While many other rifle cartridges evolved by the time of the First World War to contain a bullet of spitzer design (pointed-nose shape), the Carcano cartridge retained its original 1891 design, which included a blunt, rounded-nosed bullet, to the end of World War II.

The two bullet designs produced radically different wound ballistic characteristics; Haag tells us. Doctors and forensic ballistic experts were more familiar with wounds produced by the modern pointed-nosed bullet; and far less familiar with those produced by these long, round-nosed projectiles. This led to misstatements of fact by doctors at Parkland Hospital in Dallas and confusion at the autopsy in Bethesda, Maryland.

Haag had two Model 91/38 Carcano rifles at his disposal to conduct firing tests and a quantity of the now-rare Winchester 6.5 Carcano ammunition.

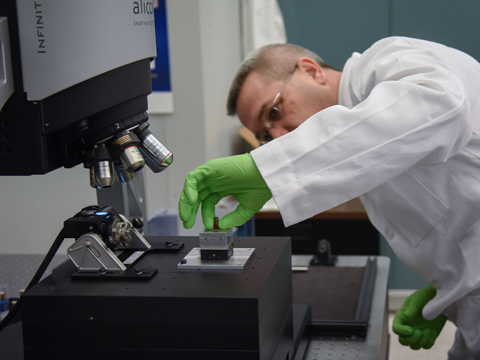

Using a Infinition Doppler radar system, not available in 1963, to determine the G1 ballistic coefficient of the WCC bullets, Haag determined that the WCC bullets would have had a velocity of 1,967 ft/s (600 m/s) at 70 yards – the distance at which President Kennedy and Governor Connally were struck by a single-bullet – and 1,914 ft/s (583 m/s) at 90 yards – the distance at which the president was struck by the fatal head shot.

Wound ballistic characteristics

Haag reports that there is a common expectation that exit wound from high-velocity rifle bullets are larger than the entrance wounds. However, in the case of the WCC 6.5mm Carcano bullets, this is simply not true. Haag found in firing test after firing test that the WCC bullet was extremely stable at it penetrated soft tissue, producing entry and exit wounds that were nearly indistinguishable.

Snapshots of WCC rounds fired through ballistic gelatin and ballistic soap (simulating soft tissue) show the long, heavy cylindrical bullet remains intact and nose-forward during penetration.

By comparison, Haag found that spitzer (pointed) bullet designs began yawing almost immediately (after about 4 inches (10 cm) of penetration) upon entering a block of ballistic soap and undergoes deflection form its original flight path.

Of particular significance, especially in the case of the Kennedy assassination, the WCC bullet lost very little velocity during the perforation process, especially compared with spitzer (pointed) military rifle bullets.

Tracking numerous test firings with the Infinition Doppler radar system, Haag demonstrates that the velocity loss experienced by the WCC Carcano bullets, after perforating a 6-inch long block of ballistic soap (simulating the soft tissues of President Kennedy’s neck) ranged from 150 to 180 ft/s. That means that the WCC bullet exiting the president’s throat would have a residual velocity of approximately 1,800 ft/s – more than enough to perforate anything in the car, including steel.

Even more significant is the fact that Haag’s Doppler radar plots also showed that these bullets always entered a yawing motion after exiting the soft tissue simulants.

“This fact coincides with the yawed entry wound in Governor Connally’s back,” Haag writes.

Haag also discusses the bullet wipe around the bullet hole in the back of President Kennedy’s coat (establishing a certain back-to front bullet path) and the fact that a bullet fired at a 27-degree downward angle (often used by conspiracy advocates, without any testing, to explain the elongated entrance wound on Governor Connally’s back) still produces a round entrance hole.

Given Haag’s findings, the position of Kennedy and Connally at the time of the shooting, and the lack of any other bullet damage to the presidential limousine that could be associated with a WCC bullet traveling at 1,800 ft/s – can there really be any doubt about the validity of the single-bullet theory?

The fatal head shot

Haag also found through testing – as did John K. Lattimer and military wound ballistician Larry M. Sturdivan – that the WCC Carcano bullet had the ability to “totally change character” and behave more like a soft-point hunting bullet, yawing and deflecting, when its nose-area was breeched by striking thick skull bone.

The unique properties of the WCC Carcano bullet – in particular, its ability to produce different-looking types of wounds depending on whether striking soft tissue or hard bone – were not known to law enforcement and medical examiners in 1963 and remain little known or understood today.

Consequently, the autopsy pathologists at Bethesda Medical Center on the night of November 22, 1963, were faced with trying to make sense of wounds in the president’s body that had all the characteristics of two different types of bullets.

In reality, Haag assures us, the wounds were produced by one unique type of bullet – the WCC 6.5mm Carcano bullets fired from Oswald’s rifle.

There’s much more in Haag’s dissertation worthy of attention, including a wealth of photographs, charts, and illustrations.

As lifelong wound ballistician Larry Sturdivan once observed: “Physical evidence is always consistent with the truth – even if we don’t immediately understand it, or can’t fully explain it.” [END]