Interview of a Reluctant Witness to the Tippit Shooting

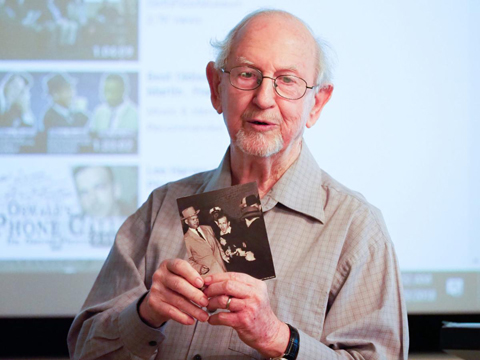

By DALE K. MYERS

Jack Ray Tatum’s eyewitness account of the Tippit shooting, offered fifteen-years after the fact, has intrigued researchers for nearly forty-years.

While rummaging through my files recently, I came across bits and pieces of the story that I don’t believe have been talked about before and may color your perception of what Tatum said and what others claimed he told them.

How Tatum ended up on Tenth Street

On November 22, 1963, Jack Ray Tatum was a 24-year-old medical photographer working for Baylor University Medical Center. In an odd turn of events, Tatum ended up at the epicenter of the Oak Cliff shooting event that led to the arrest of Lee Harvey Oswald.

On March 3, 1983, Tatum told me how he came to be on Tenth Street and witnessed Officer J.D. Tippit’s encounter with Oswald: “I lived in Oak Cliff at the time. It was before Christmas, and I had gone into a jewelry store to purchase some gifts for my wife – a watch and a ring – and was coming back around the corner to go to another shop there on Jefferson, and just happened by and saw the police officer stopping this individual…” [1]

Asked where the jewelry store was located, Tatum said, “It was Gordon’s Jewelry, in that same block that I was in, I was just making a – I hooked a left and turned and come back and hooked another right. We heard the news of the president being shot over the television that was in the jewelry store at the time.” [2]

Tatum didn’t explain at the time why he would have needed to cut through the adjoining residential neighborhood to get to “another shop on Jefferson” (couldn’t he just make a U-turn on the wide boulevard?). I assumed at the time that the shop that Tatum was referring to was located somewhere west of the Jefferson and Denver intersection. An explanation for his detour through the residential area adjoining Jefferson Boulevard eventually surfaced three years later.

In the spring of 1986, Katie A. Pearson, a 27-year-old researcher at London Weekend Television, contacted both Jack Ray Tatum and former House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) investigator John Moriarty, Jr., and questioned them as part of the pre-production for the television program, “On Trial: Lee Harvey Oswald,” which was subsequently broadcast in the U.S. on Showtime on November 21-22, 1986.

During a May 13, 1986, interview, Tatum told Pearson that on the day of the assassination, he had some hours owed him and was allowed to take the afternoon off. “My boss said why [don’t] I go downtown to photograph Kennedy? As I was going downtown, there was an awful lot of crowds and cars and I decided not to go. So, I went to Oak Cliff, where I lived at the time. I stopped at Gordon’s Jewelers on Jefferson and purchased a watch and ring on [layaway] for my wife. While I was in the store, there was a bulletin come over the TV in the jeweler’s store saying Kennedy had been shot. I was planning to go from there to a friend of mine who owned a bar, Hank Reiser, at the Mardi Gras.” [3]

The bar owner, Harold F. “Hank” Reiser, age 50, lived at 311 E. 12th, Apt. 112, just around the corner from the bar, with his wife, “Honey”. [4]

Tatum told Pearson that he had to make a detour to get to the bar, which was also on Jefferson, but some distance west. Instead of making a U-turn on Jefferson, he had to turn left on Denver and back track to avoid a central island. [5]

In a diagram provided to Pearson, Tatum located Gordon’s Jewelry store in the 500 block of east Jefferson Boulevard, just west of Denver and Club Mardi Gras on E. Jefferson, just east of Patton. [6]

However, Tatum’s 1986 recollection was in error. The only Gordon’s Quality Jewelry store in Oak Cliff in 1963 was actually located at 330 W. Jefferson Blvd., between Bishop and Madison – seven blocks west of the location specified by Tatum.

Tatum’s recalled location for Club Mardi Gras was also in error. The bar was actually located at 308 E. Jefferson Blvd. near Storey – two blocks west of the location that Tatum also identified in the diagram.

Given the true locations of the two establishments, Tatum’s explanation of how he ended up on Tenth Street doesn’t seem to ring true.

If Tatum had left Gordon’s Quality Jewelers intent on driving to Club Mardi Gras, as he claimed in 1986, he would have driven three blocks past the club before realizing he’d missed his destination. Was he day-dreaming? Or is there another explanation for Tatum’s departure onto Tenth Street?

Contemplating a purchase

The likely reason for Tatum’s presence on Tenth Street surfaced during a May 17, 1986, telephone interview conducted by Katie Pearson with former HSCA investigator John Moriarty, Jr.

Moriarty recalled that he had “spent a great many weeks trying to locate” Jack Ray Tatum after receiving a tip. Moriarty told Pearson that HSCA investigators had “interviewed over 300 local residents and shop owners around the Oak Cliff area, scene of the Tippit shooting, to try to find new witnesses. Moriarty was told of Tatum by a jeweler.” No doubt, the jeweler was the merchant at Gordon’s Quality Jewelers. [7]

According to Moriarty, the jeweler told him that on the day of the assassination, “Tatum was in the process of buying a precious stone and couldn’t decide whether he could afford it so he went for a drive around the block, taking time to come to a decision. It was on this drive that he witnessed the murder of Tippit.” [8]

Given the jeweler’s account, Tatum’s actions on November 22nd suddenly make sense. Leaving Gordon’s Quality Jewelers in the 300 block of west Jefferson, Tatum headed east contemplating the potential jewelry purchase. He had traveled about 7/10ths of a mile (a five-minute drive under normal conditions) when he reached the intersection of Jefferson and Denver – the moment he apparently had made up his mind about the purchase. He then turned north onto Denver and west on Tenth, with the intention of circling the block and heading back to the jeweler. Unfortunately, his return journey was interrupted by the murder he witnessed on Tenth Street.

Club Mardi Gras

Where does Hank Reiser’s Club Mardi Gras fit into the story?

In a March 18, telephone interview, Tatum told Katie Pearson that immediately after witnessing the Tippit shooting “he rang his wife to tell her what happened. [Her] company closed early that day and he picked up his wife from work and they went home to watch the news. ‘When we saw pictures of Oswald, I knew he was the one that shot Tippit.’” [9]

Two months later, in a face-to-face meeting with Pearson, Tatum gave a slightly different account. Tatum said that after he left the Tippit shooting scene, “Before I did anything, I called my wife and said, I just witnessed something very unusual: an officer had been shot. It was just like it was on the TV. My mind was saying, ‘Could this be real?’ It was the first time I’d ever seen someone shot. She worked for National Banker’s Life Insurance, downtown on Commerce. She said he company was letting her out for the rest of the day.

“So, then I went to my friend Hank at the Mardi Gras Club and said, ‘I just saw the damnedest thing: I saw an officer shot.’ He asked me if it was Tippit, since Tippit worked that area. Then, probably, I went home. My wife was there and also some friends. We were watching television and I was telling the story about Tippit and they showed a picture of Oswald as the suspect assassin of Kennedy and I said, ‘That’s the guy I saw.’ I knew it was him.” [10]

In this version, Tatum’s wife, Mavis, apparently found her own way home. [11]

Tatum’s inclination to call his wife immediately after the shooting and report what he had witnessed seems natural. But, where would he place such a call from? A nearby public pay telephone would have been the solution at the time. Where was the nearest pay phone? The one that leapt into Tatum’s mind was probably Hank Reiser’s Club Mardi Gras, located just three blocks from the Tippit shooting scene.

Although Tatum referred to Reiser as “a friend”, the club owner may have been nothing more than a casual acquaintance. During a 1984 conversation, Tatum didn’t know how to spell Reiser – offering ‘Rizer’ or ‘Riser’ as possible spellings – which indicates that Tatum didn’t know Reiser that well. [12]

Tatum later claimed that Reiser knew Tippit well. Tatum told me in 1984, “I know that Tippit knew most of the people in that area. There’s a little private club around the corner there called [Club] Mardi Gras – Hank Reiser used to run it. But Tippit used to stop there occasionally, so he (Tippit) made a point to know most of the people in that area.” [13]

While Tippit might have made stops at Club Mardi Gras as part of his official duties (Tippit wasn’t known as a drinker in his off hours), and Tatum and Reiser may have spoken of Tippit in the aftermath of November 22nd, it’s unlikely that Tippit’s name came up in any conversation between Tatum and Reiser on the day of the shooting.

In 1984, I asked Tatum if anyone at the scene of the shooting knew that the murdered officer was named ‘Tippit’? Tatum replied, “No, I don’t think so. I don’t recall anyone saying – as a matter of fact, I know they didn’t, because I went to that club right after that and was talking to Hank [Reiser] and he asked me who it was and I told him, ‘No,’ that as far as I knew the policeman was unidentified.” [14]

It would appear that Tatum’s stop at Club Mardi Gras was an afterthought, born out of the murder he had inadvertently witnessed and his desire to find a public telephone from which he could contact his wife.

None of these latter memory lapses seem suspicious – all of it amounts to a jumbling of events that, given the passage of time, would be expected.

Keeping the secret

Why didn’t Tatum come forward and offer his version of events back in 1963?

During her March, 1986, telephone interview, Tatum told Katie Pearson, “I never [came] forward and told them (law enforcement) I was a witness. I didn’t want to get involved at that particular time… I didn’t think it was necessary for me to become involved.” [15]

Tatum elaborated in a later face-to-face meeting, “I thought they had enough witnesses and enough information. I didn’t think I could add anything. There were a lot of people calling in, saying they had witnessed this and that. So, I thought I would just be confusing the matter. When they were getting witnesses to go to the Warren Commission, I considered coming forward at that point. But, I thought, they hadn’t missed me. No one had mentioned I was there.” [16]

Katie Pearson later reported, “After the assassination, Tatum was very concerned about the rumors of a conspiracy, particularly a Mafia one. This may have been another reason for his remaining anonymous. Fifteen years later, Congressional Assassination Committee investigators appeared at his office. ‘I’m not sure how they found me. When the two people walked in my office, they had on trench coats. One was called Moriarty.’ Tatum thought he was about to be the Mafia’s latest victim.” [17]

HSCA investigator John Moriarty later told Pearson that he “couldn’t remember how he had traced Tatum but remembers vividly one evening turning up at the hospital where Tatum worked and asking to speak with him. Moriarty wasn’t sure he (Tatum) was the right man but the first thing Tatum said was ‘How did you find me?’” [18]

Tatum always thought that the HSCA investigator found him through Marion Carlton, his boss at Baylor Medical Center. Tatum had told Carlton about what he had witnessed on Tenth Street and Carlton was friendly with Wes Wise, the former Dallas Mayor and sports announcer. Tatum suspected that Wise learned he was a witness through Carlton and that Wise was the one that told HSCA investigators. [19]

In fact, as the interviews conducted by Katie Pearson show, John Moriarty learned of Jack Tatum from a merchant at Gordon’s Quality Jewelers and subsequently traced him to the Baylor Medical Center.

Murder on Tenth Street

As most aficionados of the assassination story know, Tatum’s account of what took place on Tenth Street largely matches what has been known since November 22, 1963 – with one key exception.

In 1986, Tatum told Katie Pearson essentially what he had told me three years earlier: “As I started to turn left onto Tenth Street (from Denver), I saw a squad car and a young white male, he was walking east, the same direction the squad car was going. At that point, both were coming towards me. I made my turn and started down Tenth Street.

“As I approached the car, this individual (Oswald) was standing looking into the window. He had both hands in a zipper jacket pockets and he was leaning towards the squad car and I’m not sure if the window was down or not but he was talking into the car with the officer sitting behind the driver’s wheel. It looked as if Oswald and Tippit were talking to each other. There was a conversation. It did seem peaceful. I thought to myself, ‘I wonder what he’s been called over to the car for?’

“As I continued on, past them both, I think I must have heard the shots somewhere around the junction of Tenth and Patton. I think he fired three shots and then a fourth shot; it could have been two and a third. They were very loud and I thought, ‘What the hell was that?’ I stopped or slowed down and looked. I’m not sure in what order.” [20]

The final shot

Tatum was the only alleged witness to what happened next – this being the only deviation of his account from all others.

Tatum told Pearson, “When I turned around, the only thing I can remember seeing was an officer lying in the street on the left side of the car, still on the road side of the car. The door was open. I did not see Tippit fall.

“He was already down and I saw a person (positively identified by Tatum as Oswald) with a gun in his hand and he turned around, as if he was going to run off or walk off and as he got to the rear of the car, he hesitated and walked around the squad car (towards the officer) and shot a fourth time. It could have been a third.” [21]

Tatum stated that six to ten seconds elapsed between the penultimate shot and the last shot.

“He was blocking my view of Tippit,” Tatum told Pearson. “Oswald got within six and eight feet of Tippit. I saw him aim his gun and shoot and I could see the officer and Oswald. I’m not sure he (Oswald) actually obscured my view; maybe I was looking at him (Oswald).” [22]

Tatum stated that he had a clear view of the final shot at an oblique angle.

“He (Oswald) wasn’t panicking, that was for sure,” Tatum said. “The one characteristic about Oswald that I saw and will never forget was that his mouth seemed to curl up as if he was smiling. And I saw that when he was looking into the squad car before the shots. I noticed that same characteristic when I saw him (Oswald, later) on TV.

“I saw Oswald turn around and look in my direction. At the same time, I saw a lady (Helen Markham) on the corner, down on her knees facing Patton. She was covering her head; she thought she was going to be shot, I guess. I saw Oswald turn around and start to walk towards my car and then he broke into a fast trot in my direction, up the street. At some point, I put my car in gear and went away from him west. He went around the corner (on Patton) south.

“When he disappeared, it seemed like there were people coming out of houses or on the sidewalk. All of a sudden there were people there. So, I backed my car up and stopped and got out and went over to Tippit. [23]

Confusion at the scene

“There was a lot of confusion at that point,” Tatum told Pearson. “There was a cab driver (William Scoggins) there on the corner. Someone got in the squad car and tried to use the radio and I remember someone telling him to stay off the air.

“There was another person (Ted Callaway) who picked up the officer’s gun which was partly underneath him. He said, ‘Let’s go get him.’ I said, ‘You better put that gun down, otherwise the police are going to think you killed the officer.’

“The ambulance was there almost immediately. And almost immediately, there were police there in marked and unmarked cars. They went house-to-house to search. I believe the ambulance was there and gone before the police arrived. There were plenty of witnesses. I took Mrs. Markham over to the policeman who was taking down information and then I left.

“Mrs. Markham was closer than I was so I assumed she had a better view than I did. She was saying one thing, ‘I have to get to work.’

“Then I took Mrs. Markham over to the policeman and she described what he had on, she said dark jacket and light trousers. I thought that was the reverse I saw. I would have sworn he had on a light-colored zipper jacket, dark trousers and what looked like a T-shirt on. It was unusual weather, in that it was not cold. My description of what he was wearing was the reverse of what was put out.” [24]

Like many other witnesses, Tatum was unsure of the exact time of the shooting. He thought it was between 12:45 and 1 p.m. [25]

My own investigation, detailed in With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit (Oak Cliff Press, 1998 and 2013), pins the shooting to about 1:14:30 p.m.

Tatum vs. Callaway

Much of what Tatum told Pearson in 1986 had been told to me in 1983 using nearly identical language – a good indication that Tatum’s account is essentially true – or, at least, the way he has always told it.

It should be remembered, however, that many of the details offered by Tatum twenty-years after the fact had been widely known since the assassination, many of them published in newspaper accounts at the time.

The one significant detail that differs from all other accounts is the alleged delay of the final shot.

In 1983, Tatum told me that “not more than thirty-seconds” elapsed between the initial burst of gunfire and the final shot. Tatum said that Oswald “acted as if he was going to leave and hesitated and went back around the squad car and cautiously approached him and shot him again.” [26]

In 1986, Tatum shortened the time considerably, telling Katie Pearson that just six to ten seconds elapsed between the first shots and the last.

My own timings, based on Tatum’s description, places the elapsed time at not-less-than 25 seconds. The dimensions of Tippit’s squad car, a 1963 Ford Galaxie 500, precludes anyone from navigating the distance in the manner described by Tatum any quicker.

The timing suggested in Tatum’s account is a particular problem given Ted Callaway’s testimony that he instantly recognized the gunfire as pistol shots (others nearby thought it was firecrackers), jumped up from his office chair, dashed thirty-feet to the sidewalk on Patton and looked north toward Tenth just in time to see Oswald burst through the hedges at Tenth and Patton.

Callaway could have easily covered the dash from his office perch to the sidewalk on Patton in 15-seconds. Oswald had to cover more than three times that distance in the same time period. How could Oswald accomplish such a feat if he lingered for any length of time at the crime scene?

In addition, Tatum is the only witness who described two distinct bursts of gunfire. Not only did other eyewitnesses describe a single fusillade, but Tatum’s account includes a considerable interval between the initial gunshots and the final shot. None of the other witnesses recall such an event.

Ted Callaway, a Marine Corps combat veteran of World War II (survivor of Iwo Jima, Saipan and Guadalcanal) and, in my opinion, the most credible of all of the eyewitnesses, was very specific about the number of gunshots and their cadence. Callaway likened the five gunshots he heard to the rhythm of Morse Code he learned in the Marine Corps: bam – bam – bam-bam-bam. [27]

According to Callaway, all of the gunshots came at once, with only a slight hesitation between the first two and the last three. What he described was nothing like the interval that would have been heard if Tatum’s account were true.

When I told Callaway of Tatum’s version of the shooting in 1996, he simply didn’t believe it.

“That just didn’t happen,” Callaway told me. “Boy, those shots are as clear in my ear today as the day it happened. Bam. Bam. Bam, bam, bam. Just like that. The guy next to me said, ‘Somebody’s shooting fireworks!’ and I said, ‘Fireworks, hell! Those are pistol shots!’ When you’re in the Marines you just learn different things like that. And with that, I’m on my feet and out the door and, boy, I could move, and just as I got to the sidewalk – which is about thirty-feet away, I guess – I looked to my right and there’s Oswald jumping through the hedge.” [28]

“If someone tried to convince you that there were four shots and a short pause and then another one fired, you wouldn’t believe that?” I asked.

“No, I wouldn’t,” Callaway answered, repeating the cadence he recalled, “Bam – bam – bam, bam, bam.”

Callaway told me that he tried to convince police on the day of the shooting of what he heard: “They came down to the lot and said, ‘How many shots did you hear?’ and I said, ‘I heard five.’ They said, ‘Other people said they only heard three.’ I said, ‘Well, they’re wrong.’ I said, ‘Five.’ Well, later they came back and said, ‘Well, we only found three shell casings.’ I said, ‘Well, there’s more up there in that yard or in that hedge or someplace.’ So, they were still convinced that there was just three. But later that same day, they came back and said they found another shell casing. ‘So, he fired four shots.’ And I said, ‘Well, if you keep looking, why, you’ll find the other one unless somebody picked it up for a souvenir, or something.’” [29]

Callaway’s belief that a souvenir hunter had grabbed up the fifth discarded shell casing turned out to be true. [30]

In short, Ted Callaway was an excellent witness – clear and consistent over a span of thirty-three years about what he heard, saw and did. Unlike Tatum, Callaway’s story has been part of the published record since the moment Tippit was gunned down.

Baffled investigators

Despite that record, HSCA investigator John Moriarty made much of Tatum’s final shot, claiming that Tatum’s testimony “corroborated the medical evidence which had baffled the investigators. The autopsy report showed that three bullets had hit Tippit in the stomach and that an extra shot had been fired from a different angle as though someone had been shooting from a high level.” Moriarty claimed that Tatum was “one of the best witnesses to the Tippit shooting as he could explain the angle of the fourth shot.” [31]

Yet, none of Moriarty’s statements are true. The autopsy report shows that Tippit was struck three times in the chest (not the stomach) – one of the wounds being superficial – and once in the head. All of the bullet trajectories were at upward angles. Contrary to Moriarty’s claims, there is no way to determine from the Tippit autopsy report the order in which the shots were fired, and more specifically, if the head shot was, in fact, the last shot.

Presumably, the bullet which struck Tippit in the right temple is the one that “baffled the investigators”, according to Moriarty, given that its trajectory resulted in the steepest upward angle. However, it should be underscored that Tatum never said that the final shot was fired into Tippit’s skull. In fact, given Tatum’s distance and angle of view, he was not in a position to see where the bullet struck.

It was Moriarty’s suggestion – not Tatum’s – that the final shot was fired into Tippit’s skull. Moriarty apparently based his conclusion exclusively on the fact that the trajectory of the head shot was steeper than the other bullet wounds. From this, Moriarty extrapolated a theory – that the head shot indicated that the killer was someone other than Oswald and that “whoever shot Tippit was determined that he shouldn’t live and he was determined to finish the job properly.” [32]

The HSCA’s Final Report memorialized Moriarty’s theory as fact, while simultaneously seeking to support the HSCA’s view that organized crime was behind the “probable conspiracy” to assassinate Kennedy, [33] when it wrote:

Moriarty and the HSCA apparently failed to consider that the upward trajectories of the bullets – including the fatal head wound – could easily be attributed to the fact that Tippit was falling away from Oswald as the bullets struck.

More importantly, the HSCA attributed the claim that Oswald stood over Tippit and shot him at “point blank range in the head” to Tatum. However, Tatum never said he saw Oswald shoot Tippit in the head. The presumption that the final shot was fired into Tippit’s skull was entirely Moriarty’s.

Perhaps the HSCA felt it was more expedient and in keeping with their conclusion of a “probable conspiracy” in the Kennedy assassination to leave a hint that Oswald’s killing of Tippit was more than just an effort to escape capture.

One saving grace

While Tatum’s account is rich with detail, it is worth noting that there is nothing in his account that stands out as having significantly altered what we know of the shooting – with the exception of the delayed final shot.

Oddly, that may be the one saving grace of Tatum’s account. After all, who would concoct a story that includes a significant deviation from all other accounts; a variation that might easily be disproven and thereby undermine one’s own credibility? And therein lies the attraction of Tatum’s account.

While there are several good reasons to dismiss Tatum’s account of the final moments of the Tippit shooting as a false recollection or a misperception of the true event, there is nothing that disproves it with absolute certainty. Conversely, there is nothing that supports it.

Like many things associated with the JFK assassination saga, Jack Ray Tatum’s account lies in that nebulous gray area. It could be true. Of course, accepting the fact that it might be true, doesn’t prove that it is.

While Jack Ray Tatum may very well have happened upon Officer J.D. Tippit’s encounter with Oswald, just as he belatedly claimed, it’s easy to see now that history would have been better served had he not given in to his desire to hide in the shadows. [END]

Source notes:

[1] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum, March 3, 1983, p.1

[2] Ibid, p.13

[3] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.1

[4] Reiser died in 1969 at age 55 of an apparent heart attack.

[5] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.1

[6] Diagram by Jack Ray Tatum, May 13, 1986

[7] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[8] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[9] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with Jack Ray Tatum, Saturday, March 18, 1986, p.1

[10] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.4

[11] Tatum told Pearson that he “probably” went home after leaving Club Mardi Gras, an indication that he wasn’t sure whether he picked his wife up at work as he originally told Pearson two months earlier.

[12] Telephone interview of Jack Ray Tatum, January 17, 1984, pp.20-21

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with Jack Ray Tatum, Saturday, March 18, 1986, p.1

[16] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.4

[17] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with Jack Ray Tatum, Saturday, March 18, 1986, p.1

[18] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[19] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.4

[20] Ibid., pp.1-2

[21] Ibid., p.2

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., p.3

[25] Ibid.

[26] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum, March 3, 1983, pp.7-8, 9

[27] Interview of Ted Callaway, April 9, 1996, p.12

[28] Ibid., pp.14, 17

[29] Ibid., p.12

[30] Myers, Dale K., With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, Oak Cliff Press, 2013, p.334

[31] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[32] Ibid.

[33] The HSCA’s conclusion of a “probable conspiracy” was based almost exclusively on acoustic evidence which was later proven false by the National Academy of Sciences.

[34] House Select Committee on Assassinations, Final Report, pp.59-60

[35] Ibid., p.60, footnote 14

[36] Myers, Dale K., With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, Oak Cliff Press, 2013, Rendered diagram of bullet trajectories, p.303

While rummaging through my files recently, I came across bits and pieces of the story that I don’t believe have been talked about before and may color your perception of what Tatum said and what others claimed he told them.

How Tatum ended up on Tenth Street

On November 22, 1963, Jack Ray Tatum was a 24-year-old medical photographer working for Baylor University Medical Center. In an odd turn of events, Tatum ended up at the epicenter of the Oak Cliff shooting event that led to the arrest of Lee Harvey Oswald.

On March 3, 1983, Tatum told me how he came to be on Tenth Street and witnessed Officer J.D. Tippit’s encounter with Oswald: “I lived in Oak Cliff at the time. It was before Christmas, and I had gone into a jewelry store to purchase some gifts for my wife – a watch and a ring – and was coming back around the corner to go to another shop there on Jefferson, and just happened by and saw the police officer stopping this individual…” [1]

Asked where the jewelry store was located, Tatum said, “It was Gordon’s Jewelry, in that same block that I was in, I was just making a – I hooked a left and turned and come back and hooked another right. We heard the news of the president being shot over the television that was in the jewelry store at the time.” [2]

Tatum didn’t explain at the time why he would have needed to cut through the adjoining residential neighborhood to get to “another shop on Jefferson” (couldn’t he just make a U-turn on the wide boulevard?). I assumed at the time that the shop that Tatum was referring to was located somewhere west of the Jefferson and Denver intersection. An explanation for his detour through the residential area adjoining Jefferson Boulevard eventually surfaced three years later.

In the spring of 1986, Katie A. Pearson, a 27-year-old researcher at London Weekend Television, contacted both Jack Ray Tatum and former House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) investigator John Moriarty, Jr., and questioned them as part of the pre-production for the television program, “On Trial: Lee Harvey Oswald,” which was subsequently broadcast in the U.S. on Showtime on November 21-22, 1986.

During a May 13, 1986, interview, Tatum told Pearson that on the day of the assassination, he had some hours owed him and was allowed to take the afternoon off. “My boss said why [don’t] I go downtown to photograph Kennedy? As I was going downtown, there was an awful lot of crowds and cars and I decided not to go. So, I went to Oak Cliff, where I lived at the time. I stopped at Gordon’s Jewelers on Jefferson and purchased a watch and ring on [layaway] for my wife. While I was in the store, there was a bulletin come over the TV in the jeweler’s store saying Kennedy had been shot. I was planning to go from there to a friend of mine who owned a bar, Hank Reiser, at the Mardi Gras.” [3]

The bar owner, Harold F. “Hank” Reiser, age 50, lived at 311 E. 12th, Apt. 112, just around the corner from the bar, with his wife, “Honey”. [4]

Tatum told Pearson that he had to make a detour to get to the bar, which was also on Jefferson, but some distance west. Instead of making a U-turn on Jefferson, he had to turn left on Denver and back track to avoid a central island. [5]

In a diagram provided to Pearson, Tatum located Gordon’s Jewelry store in the 500 block of east Jefferson Boulevard, just west of Denver and Club Mardi Gras on E. Jefferson, just east of Patton. [6]

However, Tatum’s 1986 recollection was in error. The only Gordon’s Quality Jewelry store in Oak Cliff in 1963 was actually located at 330 W. Jefferson Blvd., between Bishop and Madison – seven blocks west of the location specified by Tatum.

Tatum’s recalled location for Club Mardi Gras was also in error. The bar was actually located at 308 E. Jefferson Blvd. near Storey – two blocks west of the location that Tatum also identified in the diagram.

Given the true locations of the two establishments, Tatum’s explanation of how he ended up on Tenth Street doesn’t seem to ring true.

If Tatum had left Gordon’s Quality Jewelers intent on driving to Club Mardi Gras, as he claimed in 1986, he would have driven three blocks past the club before realizing he’d missed his destination. Was he day-dreaming? Or is there another explanation for Tatum’s departure onto Tenth Street?

Contemplating a purchase

The likely reason for Tatum’s presence on Tenth Street surfaced during a May 17, 1986, telephone interview conducted by Katie Pearson with former HSCA investigator John Moriarty, Jr.

Moriarty recalled that he had “spent a great many weeks trying to locate” Jack Ray Tatum after receiving a tip. Moriarty told Pearson that HSCA investigators had “interviewed over 300 local residents and shop owners around the Oak Cliff area, scene of the Tippit shooting, to try to find new witnesses. Moriarty was told of Tatum by a jeweler.” No doubt, the jeweler was the merchant at Gordon’s Quality Jewelers. [7]

According to Moriarty, the jeweler told him that on the day of the assassination, “Tatum was in the process of buying a precious stone and couldn’t decide whether he could afford it so he went for a drive around the block, taking time to come to a decision. It was on this drive that he witnessed the murder of Tippit.” [8]

Given the jeweler’s account, Tatum’s actions on November 22nd suddenly make sense. Leaving Gordon’s Quality Jewelers in the 300 block of west Jefferson, Tatum headed east contemplating the potential jewelry purchase. He had traveled about 7/10ths of a mile (a five-minute drive under normal conditions) when he reached the intersection of Jefferson and Denver – the moment he apparently had made up his mind about the purchase. He then turned north onto Denver and west on Tenth, with the intention of circling the block and heading back to the jeweler. Unfortunately, his return journey was interrupted by the murder he witnessed on Tenth Street.

Club Mardi Gras

Where does Hank Reiser’s Club Mardi Gras fit into the story?

In a March 18, telephone interview, Tatum told Katie Pearson that immediately after witnessing the Tippit shooting “he rang his wife to tell her what happened. [Her] company closed early that day and he picked up his wife from work and they went home to watch the news. ‘When we saw pictures of Oswald, I knew he was the one that shot Tippit.’” [9]

Two months later, in a face-to-face meeting with Pearson, Tatum gave a slightly different account. Tatum said that after he left the Tippit shooting scene, “Before I did anything, I called my wife and said, I just witnessed something very unusual: an officer had been shot. It was just like it was on the TV. My mind was saying, ‘Could this be real?’ It was the first time I’d ever seen someone shot. She worked for National Banker’s Life Insurance, downtown on Commerce. She said he company was letting her out for the rest of the day.

“So, then I went to my friend Hank at the Mardi Gras Club and said, ‘I just saw the damnedest thing: I saw an officer shot.’ He asked me if it was Tippit, since Tippit worked that area. Then, probably, I went home. My wife was there and also some friends. We were watching television and I was telling the story about Tippit and they showed a picture of Oswald as the suspect assassin of Kennedy and I said, ‘That’s the guy I saw.’ I knew it was him.” [10]

In this version, Tatum’s wife, Mavis, apparently found her own way home. [11]

Tatum’s inclination to call his wife immediately after the shooting and report what he had witnessed seems natural. But, where would he place such a call from? A nearby public pay telephone would have been the solution at the time. Where was the nearest pay phone? The one that leapt into Tatum’s mind was probably Hank Reiser’s Club Mardi Gras, located just three blocks from the Tippit shooting scene.

Although Tatum referred to Reiser as “a friend”, the club owner may have been nothing more than a casual acquaintance. During a 1984 conversation, Tatum didn’t know how to spell Reiser – offering ‘Rizer’ or ‘Riser’ as possible spellings – which indicates that Tatum didn’t know Reiser that well. [12]

Tatum later claimed that Reiser knew Tippit well. Tatum told me in 1984, “I know that Tippit knew most of the people in that area. There’s a little private club around the corner there called [Club] Mardi Gras – Hank Reiser used to run it. But Tippit used to stop there occasionally, so he (Tippit) made a point to know most of the people in that area.” [13]

While Tippit might have made stops at Club Mardi Gras as part of his official duties (Tippit wasn’t known as a drinker in his off hours), and Tatum and Reiser may have spoken of Tippit in the aftermath of November 22nd, it’s unlikely that Tippit’s name came up in any conversation between Tatum and Reiser on the day of the shooting.

In 1984, I asked Tatum if anyone at the scene of the shooting knew that the murdered officer was named ‘Tippit’? Tatum replied, “No, I don’t think so. I don’t recall anyone saying – as a matter of fact, I know they didn’t, because I went to that club right after that and was talking to Hank [Reiser] and he asked me who it was and I told him, ‘No,’ that as far as I knew the policeman was unidentified.” [14]

It would appear that Tatum’s stop at Club Mardi Gras was an afterthought, born out of the murder he had inadvertently witnessed and his desire to find a public telephone from which he could contact his wife.

None of these latter memory lapses seem suspicious – all of it amounts to a jumbling of events that, given the passage of time, would be expected.

Keeping the secret

Why didn’t Tatum come forward and offer his version of events back in 1963?

During her March, 1986, telephone interview, Tatum told Katie Pearson, “I never [came] forward and told them (law enforcement) I was a witness. I didn’t want to get involved at that particular time… I didn’t think it was necessary for me to become involved.” [15]

Tatum elaborated in a later face-to-face meeting, “I thought they had enough witnesses and enough information. I didn’t think I could add anything. There were a lot of people calling in, saying they had witnessed this and that. So, I thought I would just be confusing the matter. When they were getting witnesses to go to the Warren Commission, I considered coming forward at that point. But, I thought, they hadn’t missed me. No one had mentioned I was there.” [16]

Katie Pearson later reported, “After the assassination, Tatum was very concerned about the rumors of a conspiracy, particularly a Mafia one. This may have been another reason for his remaining anonymous. Fifteen years later, Congressional Assassination Committee investigators appeared at his office. ‘I’m not sure how they found me. When the two people walked in my office, they had on trench coats. One was called Moriarty.’ Tatum thought he was about to be the Mafia’s latest victim.” [17]

HSCA investigator John Moriarty later told Pearson that he “couldn’t remember how he had traced Tatum but remembers vividly one evening turning up at the hospital where Tatum worked and asking to speak with him. Moriarty wasn’t sure he (Tatum) was the right man but the first thing Tatum said was ‘How did you find me?’” [18]

Tatum always thought that the HSCA investigator found him through Marion Carlton, his boss at Baylor Medical Center. Tatum had told Carlton about what he had witnessed on Tenth Street and Carlton was friendly with Wes Wise, the former Dallas Mayor and sports announcer. Tatum suspected that Wise learned he was a witness through Carlton and that Wise was the one that told HSCA investigators. [19]

In fact, as the interviews conducted by Katie Pearson show, John Moriarty learned of Jack Tatum from a merchant at Gordon’s Quality Jewelers and subsequently traced him to the Baylor Medical Center.

Murder on Tenth Street

As most aficionados of the assassination story know, Tatum’s account of what took place on Tenth Street largely matches what has been known since November 22, 1963 – with one key exception.

In 1986, Tatum told Katie Pearson essentially what he had told me three years earlier: “As I started to turn left onto Tenth Street (from Denver), I saw a squad car and a young white male, he was walking east, the same direction the squad car was going. At that point, both were coming towards me. I made my turn and started down Tenth Street.

“As I approached the car, this individual (Oswald) was standing looking into the window. He had both hands in a zipper jacket pockets and he was leaning towards the squad car and I’m not sure if the window was down or not but he was talking into the car with the officer sitting behind the driver’s wheel. It looked as if Oswald and Tippit were talking to each other. There was a conversation. It did seem peaceful. I thought to myself, ‘I wonder what he’s been called over to the car for?’

“As I continued on, past them both, I think I must have heard the shots somewhere around the junction of Tenth and Patton. I think he fired three shots and then a fourth shot; it could have been two and a third. They were very loud and I thought, ‘What the hell was that?’ I stopped or slowed down and looked. I’m not sure in what order.” [20]

The final shot

Tatum was the only alleged witness to what happened next – this being the only deviation of his account from all others.

Tatum told Pearson, “When I turned around, the only thing I can remember seeing was an officer lying in the street on the left side of the car, still on the road side of the car. The door was open. I did not see Tippit fall.

“He was already down and I saw a person (positively identified by Tatum as Oswald) with a gun in his hand and he turned around, as if he was going to run off or walk off and as he got to the rear of the car, he hesitated and walked around the squad car (towards the officer) and shot a fourth time. It could have been a third.” [21]

Tatum stated that six to ten seconds elapsed between the penultimate shot and the last shot.

“He was blocking my view of Tippit,” Tatum told Pearson. “Oswald got within six and eight feet of Tippit. I saw him aim his gun and shoot and I could see the officer and Oswald. I’m not sure he (Oswald) actually obscured my view; maybe I was looking at him (Oswald).” [22]

Tatum stated that he had a clear view of the final shot at an oblique angle.

“He (Oswald) wasn’t panicking, that was for sure,” Tatum said. “The one characteristic about Oswald that I saw and will never forget was that his mouth seemed to curl up as if he was smiling. And I saw that when he was looking into the squad car before the shots. I noticed that same characteristic when I saw him (Oswald, later) on TV.

“I saw Oswald turn around and look in my direction. At the same time, I saw a lady (Helen Markham) on the corner, down on her knees facing Patton. She was covering her head; she thought she was going to be shot, I guess. I saw Oswald turn around and start to walk towards my car and then he broke into a fast trot in my direction, up the street. At some point, I put my car in gear and went away from him west. He went around the corner (on Patton) south.

“When he disappeared, it seemed like there were people coming out of houses or on the sidewalk. All of a sudden there were people there. So, I backed my car up and stopped and got out and went over to Tippit. [23]

Confusion at the scene

“There was a lot of confusion at that point,” Tatum told Pearson. “There was a cab driver (William Scoggins) there on the corner. Someone got in the squad car and tried to use the radio and I remember someone telling him to stay off the air.

“There was another person (Ted Callaway) who picked up the officer’s gun which was partly underneath him. He said, ‘Let’s go get him.’ I said, ‘You better put that gun down, otherwise the police are going to think you killed the officer.’

“The ambulance was there almost immediately. And almost immediately, there were police there in marked and unmarked cars. They went house-to-house to search. I believe the ambulance was there and gone before the police arrived. There were plenty of witnesses. I took Mrs. Markham over to the policeman who was taking down information and then I left.

“Mrs. Markham was closer than I was so I assumed she had a better view than I did. She was saying one thing, ‘I have to get to work.’

“Then I took Mrs. Markham over to the policeman and she described what he had on, she said dark jacket and light trousers. I thought that was the reverse I saw. I would have sworn he had on a light-colored zipper jacket, dark trousers and what looked like a T-shirt on. It was unusual weather, in that it was not cold. My description of what he was wearing was the reverse of what was put out.” [24]

Like many other witnesses, Tatum was unsure of the exact time of the shooting. He thought it was between 12:45 and 1 p.m. [25]

My own investigation, detailed in With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit (Oak Cliff Press, 1998 and 2013), pins the shooting to about 1:14:30 p.m.

Tatum vs. Callaway

Much of what Tatum told Pearson in 1986 had been told to me in 1983 using nearly identical language – a good indication that Tatum’s account is essentially true – or, at least, the way he has always told it.

It should be remembered, however, that many of the details offered by Tatum twenty-years after the fact had been widely known since the assassination, many of them published in newspaper accounts at the time.

The one significant detail that differs from all other accounts is the alleged delay of the final shot.

In 1983, Tatum told me that “not more than thirty-seconds” elapsed between the initial burst of gunfire and the final shot. Tatum said that Oswald “acted as if he was going to leave and hesitated and went back around the squad car and cautiously approached him and shot him again.” [26]

In 1986, Tatum shortened the time considerably, telling Katie Pearson that just six to ten seconds elapsed between the first shots and the last.

My own timings, based on Tatum’s description, places the elapsed time at not-less-than 25 seconds. The dimensions of Tippit’s squad car, a 1963 Ford Galaxie 500, precludes anyone from navigating the distance in the manner described by Tatum any quicker.

The timing suggested in Tatum’s account is a particular problem given Ted Callaway’s testimony that he instantly recognized the gunfire as pistol shots (others nearby thought it was firecrackers), jumped up from his office chair, dashed thirty-feet to the sidewalk on Patton and looked north toward Tenth just in time to see Oswald burst through the hedges at Tenth and Patton.

Callaway could have easily covered the dash from his office perch to the sidewalk on Patton in 15-seconds. Oswald had to cover more than three times that distance in the same time period. How could Oswald accomplish such a feat if he lingered for any length of time at the crime scene?

In addition, Tatum is the only witness who described two distinct bursts of gunfire. Not only did other eyewitnesses describe a single fusillade, but Tatum’s account includes a considerable interval between the initial gunshots and the final shot. None of the other witnesses recall such an event.

Ted Callaway, a Marine Corps combat veteran of World War II (survivor of Iwo Jima, Saipan and Guadalcanal) and, in my opinion, the most credible of all of the eyewitnesses, was very specific about the number of gunshots and their cadence. Callaway likened the five gunshots he heard to the rhythm of Morse Code he learned in the Marine Corps: bam – bam – bam-bam-bam. [27]

According to Callaway, all of the gunshots came at once, with only a slight hesitation between the first two and the last three. What he described was nothing like the interval that would have been heard if Tatum’s account were true.

When I told Callaway of Tatum’s version of the shooting in 1996, he simply didn’t believe it.

“That just didn’t happen,” Callaway told me. “Boy, those shots are as clear in my ear today as the day it happened. Bam. Bam. Bam, bam, bam. Just like that. The guy next to me said, ‘Somebody’s shooting fireworks!’ and I said, ‘Fireworks, hell! Those are pistol shots!’ When you’re in the Marines you just learn different things like that. And with that, I’m on my feet and out the door and, boy, I could move, and just as I got to the sidewalk – which is about thirty-feet away, I guess – I looked to my right and there’s Oswald jumping through the hedge.” [28]

“If someone tried to convince you that there were four shots and a short pause and then another one fired, you wouldn’t believe that?” I asked.

“No, I wouldn’t,” Callaway answered, repeating the cadence he recalled, “Bam – bam – bam, bam, bam.”

Callaway told me that he tried to convince police on the day of the shooting of what he heard: “They came down to the lot and said, ‘How many shots did you hear?’ and I said, ‘I heard five.’ They said, ‘Other people said they only heard three.’ I said, ‘Well, they’re wrong.’ I said, ‘Five.’ Well, later they came back and said, ‘Well, we only found three shell casings.’ I said, ‘Well, there’s more up there in that yard or in that hedge or someplace.’ So, they were still convinced that there was just three. But later that same day, they came back and said they found another shell casing. ‘So, he fired four shots.’ And I said, ‘Well, if you keep looking, why, you’ll find the other one unless somebody picked it up for a souvenir, or something.’” [29]

Callaway’s belief that a souvenir hunter had grabbed up the fifth discarded shell casing turned out to be true. [30]

In short, Ted Callaway was an excellent witness – clear and consistent over a span of thirty-three years about what he heard, saw and did. Unlike Tatum, Callaway’s story has been part of the published record since the moment Tippit was gunned down.

Baffled investigators

Despite that record, HSCA investigator John Moriarty made much of Tatum’s final shot, claiming that Tatum’s testimony “corroborated the medical evidence which had baffled the investigators. The autopsy report showed that three bullets had hit Tippit in the stomach and that an extra shot had been fired from a different angle as though someone had been shooting from a high level.” Moriarty claimed that Tatum was “one of the best witnesses to the Tippit shooting as he could explain the angle of the fourth shot.” [31]

Yet, none of Moriarty’s statements are true. The autopsy report shows that Tippit was struck three times in the chest (not the stomach) – one of the wounds being superficial – and once in the head. All of the bullet trajectories were at upward angles. Contrary to Moriarty’s claims, there is no way to determine from the Tippit autopsy report the order in which the shots were fired, and more specifically, if the head shot was, in fact, the last shot.

Presumably, the bullet which struck Tippit in the right temple is the one that “baffled the investigators”, according to Moriarty, given that its trajectory resulted in the steepest upward angle. However, it should be underscored that Tatum never said that the final shot was fired into Tippit’s skull. In fact, given Tatum’s distance and angle of view, he was not in a position to see where the bullet struck.

It was Moriarty’s suggestion – not Tatum’s – that the final shot was fired into Tippit’s skull. Moriarty apparently based his conclusion exclusively on the fact that the trajectory of the head shot was steeper than the other bullet wounds. From this, Moriarty extrapolated a theory – that the head shot indicated that the killer was someone other than Oswald and that “whoever shot Tippit was determined that he shouldn’t live and he was determined to finish the job properly.” [32]

The HSCA’s Final Report memorialized Moriarty’s theory as fact, while simultaneously seeking to support the HSCA’s view that organized crime was behind the “probable conspiracy” to assassinate Kennedy, [33] when it wrote:

“Oswald, according to Tatum, after initially shooting Tippit from his position on the sidewalk, walked around the patrol car to where Tippit lay in the street and stood over him while he shot him at point blank range in the head. (emphasis added) This action, which is often encountered in gangland murders and is commonly described as a coup de grâce, is more indicative of an execution than an act of defense intended to allow escape or prevent apprehension. Absent further evidence – which the committee did not develop – the meaning of this evidence must remain uncertain.” [34]As an explanatory note to the “uncertainty” of the presumed execution-style head shot, the committee added this footnote:

The committee did verify from the Tippit autopsy report that there was one wound in the body that slanted upward from front to back. Though previously unexplained, it would be consistent with the observation of Jack Ray Tatum. [35]The HSCA’s explanation was disingenuous at best. In reality, there is nothing in the autopsy report to support Moriarty’s theory that the final shot allegedly witnessed by Tatum was fired into Tippit skull. Specifically, the HSCA claim that only one wound (presumably the head shot) exhibited a trajectory that “slanted upward from front to back” was a lie. In fact, all of the wounds (with the exception of the superficial wound to upper abdomen, from which no trajectory could be deduced) slanted upward front to back at varying degrees of elevation. [36]

Moriarty and the HSCA apparently failed to consider that the upward trajectories of the bullets – including the fatal head wound – could easily be attributed to the fact that Tippit was falling away from Oswald as the bullets struck.

More importantly, the HSCA attributed the claim that Oswald stood over Tippit and shot him at “point blank range in the head” to Tatum. However, Tatum never said he saw Oswald shoot Tippit in the head. The presumption that the final shot was fired into Tippit’s skull was entirely Moriarty’s.

Perhaps the HSCA felt it was more expedient and in keeping with their conclusion of a “probable conspiracy” in the Kennedy assassination to leave a hint that Oswald’s killing of Tippit was more than just an effort to escape capture.

One saving grace

While Tatum’s account is rich with detail, it is worth noting that there is nothing in his account that stands out as having significantly altered what we know of the shooting – with the exception of the delayed final shot.

Oddly, that may be the one saving grace of Tatum’s account. After all, who would concoct a story that includes a significant deviation from all other accounts; a variation that might easily be disproven and thereby undermine one’s own credibility? And therein lies the attraction of Tatum’s account.

While there are several good reasons to dismiss Tatum’s account of the final moments of the Tippit shooting as a false recollection or a misperception of the true event, there is nothing that disproves it with absolute certainty. Conversely, there is nothing that supports it.

Like many things associated with the JFK assassination saga, Jack Ray Tatum’s account lies in that nebulous gray area. It could be true. Of course, accepting the fact that it might be true, doesn’t prove that it is.

While Jack Ray Tatum may very well have happened upon Officer J.D. Tippit’s encounter with Oswald, just as he belatedly claimed, it’s easy to see now that history would have been better served had he not given in to his desire to hide in the shadows. [END]

Source notes:

[1] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum, March 3, 1983, p.1

[2] Ibid, p.13

[3] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.1

[4] Reiser died in 1969 at age 55 of an apparent heart attack.

[5] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.1

[6] Diagram by Jack Ray Tatum, May 13, 1986

[7] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[8] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[9] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with Jack Ray Tatum, Saturday, March 18, 1986, p.1

[10] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.4

[11] Tatum told Pearson that he “probably” went home after leaving Club Mardi Gras, an indication that he wasn’t sure whether he picked his wife up at work as he originally told Pearson two months earlier.

[12] Telephone interview of Jack Ray Tatum, January 17, 1984, pp.20-21

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with Jack Ray Tatum, Saturday, March 18, 1986, p.1

[16] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.4

[17] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with Jack Ray Tatum, Saturday, March 18, 1986, p.1

[18] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[19] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum by Katie Pearson, May 13, 1986, p.4

[20] Ibid., pp.1-2

[21] Ibid., p.2

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., p.3

[25] Ibid.

[26] Interview of Jack Ray Tatum, March 3, 1983, pp.7-8, 9

[27] Interview of Ted Callaway, April 9, 1996, p.12

[28] Ibid., pp.14, 17

[29] Ibid., p.12

[30] Myers, Dale K., With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, Oak Cliff Press, 2013, p.334

[31] Telephone conversation, Katie Pearson with John Moriarty, Jr., Saturday, May 17, 1986, p.1

[32] Ibid.

[33] The HSCA’s conclusion of a “probable conspiracy” was based almost exclusively on acoustic evidence which was later proven false by the National Academy of Sciences.

[34] House Select Committee on Assassinations, Final Report, pp.59-60

[35] Ibid., p.60, footnote 14

[36] Myers, Dale K., With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, Oak Cliff Press, 2013, Rendered diagram of bullet trajectories, p.303