by DALE K. MYERS with TODD W. VAUGHAN

Flash 8 or higher is required to view videos accompanying this article. Get the free plugin now.

A theory that Lee Harvey Oswald fired his first shot earlier than anyone had ever considered before is making the rounds again. But despite the accolades from uninformed circles, the theory has proven, once again, to have no factual basis. I say ‘once again,’ because we’ve heard all of this before. Déjà vu.

In their article “J.F.K.’s Death, Re-Framed,” published as a New York Times Op-Ed piece on the forty-fourth anniversary of the Kennedy assassination, Max Holland and Johann W. Rush propose once again that Oswald fired his first shot nearly three seconds earlier than previously thought and that this first shot struck a traffic pole resulting in a ricochet that missed the motorcade.

According to Holland and Rush, their theory is supported by eye and ear-witnesses to the shooting (including Amos L. Euins, the only one named in the New York Times article) and explains why Oswald missed his first and closest shot.

“Oswald still did it,” Holland and Rush assure us, but their new theory, they say, could have saved the Warren Commission from falling into disrepute because it offers a shooting sequence that is far more plausible in its timing.

New theories abound in the Kennedy assassination. In fact, we’re awash every November in new theories about what happened in Dallas. Most of these new theories are a lot of nonsense.

But, when the New York Times publishes a piece by someone like Max Holland (author of “The Kennedy Assassination Tapes,” and a forthcoming book on the Warren Commission) and Johann Rush (a television photographer, who filmed Lee Harvey Oswald demonstrating in New Orleans in August 1963) people sit up and take notice.

One expects to read a factual, accurate, and well-researched take on this very controversial subject in such a prestigious venue. Instead, Holland and Rush stumble their way through an embarrassing, ill-conceived, unsupportable theory that comes off more like ‘headline grabbing’ than anything else. What a shame.

None of this is new, of course.

Holland and Rush first floated their early-shot theory back in February, 2007, in an article entitled “1963: 11 Seconds in Dallas,” which was published on the Internet’s History News Network (HNN). Their claim that the new theory was supported by the historic record was quickly criticized for being false and misleading. [See: “Max Holland’s 11 Seconds in Dallas”] Their reaction to the criticism was to defend the indefensible and charge that those who were critical of their theory were only doing so in an effort to cover-up their own inadequate theories.

Their recent Op-Ed piece in the New York Times, and a subsequent article by Seattle lawyer Kenneth R. Scearce, posted on the John McAdams’ website The Kennedy Assassination, is nothing but a rehash of the same old, unsubstantiated claims.

Despite all of their foot-stomping, Holland and Rush cannot escape the simple truth that their theory has no support whatsoever in the historic record. They might just as well have pulled their thesis out of thin air. They started with a false premise, based on a generalization of the ear-witness accounts which described the spacing of the shots, then backward engineered “evidence” of an earlier first shot from a carefully chosen selection of eye witness accounts, all of which fail to pass a basic litmus test. When they were called out on it, they refused to acknowledge the obvious – they blew it. What a disappointment.

Back in June, I mused, “Let’s hope that any future writings from Max Holland and Johann Rush have more bite than sizzle to them.”

Apparently, the pair didn’t feel it was necessary to revise their claim and plowed forward as if nothing had happened. With only a few minor alterations, Holland and Rush foisted the same, fatally flawed theory on the unsuspecting editors and readers of the New York Times.

Nowhere in their November Times Op-Ed piece (or in their companion article, “11 Seconds in Dallas; Not Six,” now posted on Holland’s ‘washingtondecoded.com’ website) do Holland and Rush address or respond to the multitude of factual inaccuracies pointed out about their early-shot thesis back in June. Apparently they are content to look the other way and pretend their investigative and journalistic skills pass muster.

Most of what follows was covered six months ago in an article that you’ll find archived on this website. [See: June, 2007 – “Max Holland’s 11 Seconds in Dallas”] For those of you just getting up to speed, here’s the heart of their argument and the truth about their claims.

First, you should understand that this discussion is all about the timing of the first of three shots fired at the presidential motorcade. Holland and Rush’s theory is not a conspiracy theory. They are convinced Oswald did the shooting alone. Their theory purports to answer one key question about the assassination:

How did Oswald managed to miss his closest and therefore, presumably, his easiest shot?

According to Holland and Rush, the answer to that question also has the residual effect of answering two additional questions:

Why did numerous ear-witnesses think the last two shots were bunched closer together?

The Shot That Missed

Practically everyone who has studied the assassination and who believes there was a lone assassin agrees today that of the three bullets fired that day, it was most likely the first bullet that missed the motorcade – the next two bullets striking Kennedy and Connally. There, however, the agreement ends.

The general consensus has been that the first shot was fired immediately prior to Z160, based largely on the actions of Governor Connally and Mrs. Kennedy who seem to be reacting to the first shot in subsequent frames.

Many believe Oswald’s first shot struck the branch of an intervening oak tree and was deflected, missing the limousine entirely.

Others, like Reclaiming History author and renowned prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, noted that Oswald’s first and closest shot was also the most difficult shot of the three – a tracking shot, moving left to right. The last two shots were fired while the limousine was moving directly away from and on a slight incline from the sniper’s firing position, a fact which made Oswald’s target virtually stationary.

Still others suggest that Oswald simply ‘botched it’ – his missed shot attributed to ‘buck fever,’ a term familiar to deer hunters everywhere.

According to Holland and Rush, all of these speculative offerings are wrong. It is their contention that Oswald fired several seconds earlier than anyone had ever considered before and that the intervening object was not an oak tree but a traffic light pole that extended out over Elm Street directly in front of the main entrance of the Texas School Book Depository.

In fact, Oswald’s first shot was fired so early, say Holland and Rush, that Abraham Zapruder hadn’t even begun taking pictures with his 8mm movie camera.

What evidence do Holland and Rush offer to support their theory? It turns out their theory is based on a potpourri of false and misleading statements, twisted logic, nonsensical assertions.

For instance, when Holland and Rush first floated their theory in mid-February, 2007, they cited the testimony of seven witnesses who they claimed supported their theory that the presidential limousine had just passed the traffic light pole at Elm and Houston when the first shot was fired.

Howard Brennan

One of those witnesses was Howard Brennan, the Dallas construction worker who was seated on a concrete wall directly across the street from the Book Depository. More importantly, Brennan was seated almost directly across from the traffic light pole that Holland and Rush believe deflected Oswald’s first shot.

Holland and Rush quote this portion of Howard Brennan’s Warren Commission testimony, taken four months after the slaying, “And after the president had passed my position, I really couldn’t say how many feet or how far, a short distance I would say, I heard this crack that I positively thought was a backfire.” [3H143]

Not only is Brennan’s March, 1964 testimony considerably vague as to the location of the president’s car at the time of the first shot, but what Holland and Rush didn’t mention (or didn’t know) is that Brennan was much more specific about the limousine’s position at the time of the first shot during two separate interviews given on the very day of the shooting.

In a Dallas Sheriff Department affidavit of November 22nd, Brennan described the presidential limousine as being “about 50 yards from the intersection of Elm and Houston” when the first shot was fired. [emphasis added] [19H470, Decker Exhibit 5323]

And in a FBI affidavit of November 22nd, the FBI reported that, “...[Brennan] said the automobile had passed down Elm Street (going in a westerly direction) approximately 30 yards from the point which he (Brennan) was seated, when he heard a loud report which he first thought to be the “backfire” of an automobile...” [emphasis added] [Howard Brennan, FBI Affidavit of Nov. 22, 1963, CD205, p.12-13]

Both measurements relate to an area 78 to 83 feet west of the traffic light pole cited by Holland and Rush as the cause of Oswald’s missed shot. In fact, Brennan’s estimate places the limousine approaching the R.L. Thornton Freeway sign, a landmark cited by and in accord with other witnesses who place the limousine’s position at the time of the first shot well west of where the Holland/Rush theory places it, as you will see in a bit.

And yet, for the Holland/Rush theory to be valid, the president’s limousine would had to have been located just 14 feet west of the traffic light pole at the time of the first shot in order for the pole to have occluded Oswald’s line of sight – not 78-plus feet – as Brennan estimated.

While Brennan’s estimate of the limousine’s location at the time he heard the first shot might not be completely accurate, it’s very difficult to believe that he would confuse an area one-quarter of a football field west of him with an area practically in front of him, especially considering the fact that Howard Brennan was a steamfitter working for a construction company – a position that requires a good visual sense of measurement. In any event, Brennan’s testimony certainly is not supportive of the Holland/Rush thesis.

James Jarman

Holland and Rush also cite the equally vague testimony of James Jarman, Jr., one of three Depository employees viewing the motorcade from the fifth floor, immediately below Oswald’s sniper perch: “After the motorcade turned, going west on Elm, then there was a loud shot, or backfire, as I thought it was then.” [3H204]

“After the motorcade turned...” ? How on earth does Jarman’s incredibly vague testimony place the limousine under the traffic light pole, as Holland and Rush claim? Couldn’t Jarman just as easily have been speaking about an area located another one hundred feet further west on Elm?

Why didn’t Holland and Rush mention the far more detailed testimony of Bonnie Ray Williams? Williams was another Depository employee who was with James Jarman and fellow employee Harold Norman on the fifth floor, watching the motorcade from the windows immediately below the sniper’s perch.

Williams told the Warren Commission in March, 1964, “...After the President’s car had passed my window, the last thing I remember seeing him do was, you know – it seemed to me he had a habit of pushing his hair back. The last thing I saw him do was he pushed his hand up like this. I assumed he was brushing his hair back. And then the thing that happened then was a loud shot...” [3H175]

In fact, Kennedy does brush his hair back no less than four times (as depicted in multiple amateur films) as the motorcade made its way through Dealey Plaza, the last time just as Zapruder begins filming at Z133. The limousine’s position at that moment was just passed the window from which Bonnie Ray Williams was viewing the motorcade, exactly as Williams recalled.

The key point here is that Williams also vividly recalled that the first shot (which he certainly heard with great clarity since it was fired less than ten feet over his head) was fired after Kennedy brushed his hair back (i.e., after Zapruder began filming, at Z133) – not before, as Holland and Rush theorize.

It’s worth noting that Harold Norman, who was with Williams and Jarman on the fifth floor, also testified that Kennedy was brushing his hair back just before the first shot. [3H191]

All three of these testimonies – Jarman, Williams, and Norman – appear in the same Warren Commission volume cited by Holland and Rush, the three employees having been interviewed during the same session. Yet, Holland and Rush chose to use only Jarman’s comparatively vague recollection.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out why Holland and Rush chose to ignore Bonnie Ray Williams’ descriptive and verifiable testimony – Williams’ testimony alone torpedoes their theory.

Buell Wesley Frazier

Holland and Rush also cited the testimony of Buell Wesley Frazier, a Depository employee at the front entrance, as supportive of their theory of an early shot, quoting this passage, “...just right after [the president] went by — he hadn’t hardly got by — I heard a sound...” [2H234]

Again, Holland and Rush avoid additional testimony that would clarify this vague passage. For instance, they don’t mention this exchange between Frazier and Warren Commission counsel Joseph A. Ball that follows the portion they quoted:

BALL: Were you able to see the President, could you still see the President’s car when you heard the first sound?

FRAZIER: No, sir; I couldn’t. From there, you know people were standing out there on the curb, you see, and you know it drops, you know the ground drops off there as you go down toward that underpass and I couldn’t see any of it because people were standing up there in my way, but however, when he did turn that corner there, there wasn’t anybody standing in the street and you could see good there, but after you got on past down there you couldn’t see anything.

BALL: You didn’t see the President’s car at the time you heard the sound?

FRAZIER: No, sir; I didn’t. [2H234]

So, in fact, the president’s limousine wasn’t even in Frazier’s sight at the time of the first shot. We’re not even sure that Frazier was looking at the limousine at the time of the first shot. All we can glean from Frazier’s testimony is that he heard the first shot shortly after the president passed his position.

How many feet was that? Fourteen feet, as Holland and Rush believe? Or forty-five feet, as Bonnie Ray Williams indicated? Under the circumstances, words like “hardly” and “shortly” aren’t very useful in defining such a precise distance.

Secret Service Agents

Holland and Rush also cited the equally vague testimony of three Secret Service agents (Kinney, Hickey, and Landis) as supportive of their theory: “...As we completed the left turn and [went] on a short distance, there was a shot...” [18H731]; “...the president’s car turned left at the intersection and started down an incline...After a very short distance I heard a loud report...” [18H762]; “...the president’s car and the follow-up car had just completed their turns and both were straightening out...At this moment I heard what sounded like the report of a high-powered rifle...” [18H754]

None of these reports aid us in determining the exact moment of the first shot either. If anything, they contradict the Holland/Rush theory. How? You’ll note that the Secret Service agents heard the first shot after their own car had made the turn and traveled at least some distance down Elm.

Yet, if the first shot occurred 1.4 seconds before Zapruder began filming, as Holland and Rush theorize, then the Secret Service Follow-up Car would still have been in the process of rounding the corner from Houston onto Elm. We known this for a fact because five lesser-known amateur films of the Kennedy motorcade capture the period of time immediately before Zapruder began filming. And from these films we can see that the Secret Service Follow-up Car hadn’t begun to travel down Elm Street at the time of Holland and Rush’s theorized first shot. How then can Holland and Rush claim the testimony of the three agents as supportive?

T.E. Moore

Holland and Rush’s key eyewitness to an early-shot was T.E. Moore, an eyewitness who told author Larry Sneed twenty-four years after-the-fact that “...There was a highway marker sign right in front of the Book Depository, and as the president got around to that, the first shot was fired...”

Holland argued that the highway marker sign mentioned by Moore was the cluster of small highway markers adjacent to the traffic light pole and that ‘right in front of the Book Depository’ meant right in front of the main entrance to the Book Depository.

But all of Holland’s speculation was completely unnecessary. It turns out that T. E. Moore gave a statement to the FBI a month-and-a-half after the assassination in which he spelled out exactly what sign he was talking about:

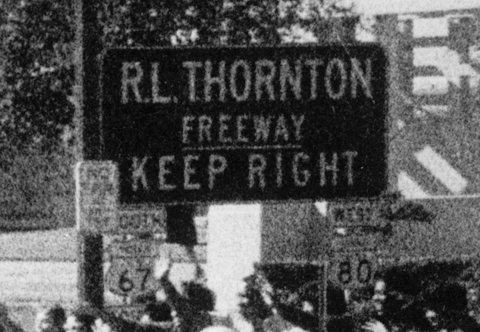

"...By the time President Kennedy had reached the [R.L.] Thornton freeway sign, a shot was fired..." [24H534]

No ambiguity there; the sign referred to by Moore was the R.L. Thornton sign, not the cluster of highway signs chosen by Holland and Rush.

Despite the fact that Moore’s earliest statement was pointed out to Holland more than six months ago, he and Rush continue to use Moore’s belated statement to author Larry Sneed as supportive of their theory. Does that sound like fair and balanced reporting?

Amos Euins

It’s interesting to note that Holland and Rush substituted Moore’s testimony with that of then-ninth grader Amos L. Euins in their New York Times Op-Ed piece (though they continue to use Moore’s belated statement in their expanded version of the article). The introduction is nearly identical in both instances:

“...No one’s memory was more exacting, though, than that of T.E. Moore...” [History News Network, “1963: 11 Seconds in Dallas,” February 19, 2007]

Unfortunately, the testimony of Amos Euins isn’t any more supportive of the Holland/Rush theory than that of T.E. Moore’s – no matter how Holland and Rush phrase it or twist it. Take a look:

In a November 22, 1963, Dallas Sheriff Department affidavit, Euins told investigators, “I saw the President turn the corner in front of me and I waved at him and he waved back. I watched the car [go] on down the street and about the time the car got near the black and white sign I heard a shot...” [19H474 Decker Exhibit 5323]

In order to convince readers of their New York Times Op-Ed piece that Euins’ testimony supported their theory, Holland and Rush were very selective in their citation. For instance, Holland and Rush didn’t mention that Euins said he ‘watched the car [go] on down the street’ before the car neared the black and white sign and he heard a shot. Nor do Holland and Rush mention that Euins was standing across the street from the Book Depository front entrance – directly across from the traffic light pole that supposedly intercepted Oswald’s first shot.

Of course, those two crucial pieces of information completely alter what Euins is saying – namely that the presidential car was not in front of him at the time of the first shot, as Holland and Rush imagine, but had proceeded down the street some unknown distance before the first shot was fired.

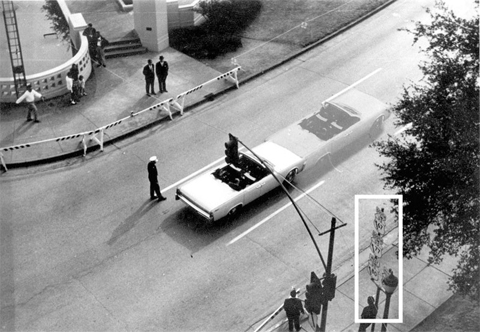

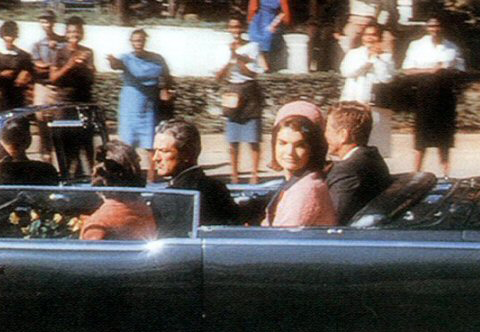

Holland and Rush’s complicity in this obvious deception is no better illustrated than in their use of a 1963 Secret Service re-enactment photograph [Figure 1] which they said shows “...the president’s limousine would have passed a black and white sign before Zapruder restarted his camera...” just as young Amos Euins described. [emphasis added]

Figure 1. Re-enactment photograph showing highway signs designated by Holland and Rush.

To be more accurate, Holland and Rush should have said that the limousine would have passed a cluster of small highway signs – not a singular black and white sign, as Euins suggested. This fact might have taken on much more significance had Holland and Rush revealed that there was more than one cluster of small black and white highway signs along Elm Street – or better yet, that there was a singular highway sign further down Elm Street.

In fact, the very next highway sign, which appears to have been black and white, was the R.L. Thornton Freeway sign located 100 feet further west on Elm Street – the same R.L Thornton Freeway sign that T.E. Moore referred to as the approximate location of the president’s car at the time of the first shot. [Figure 2] The R. L. Thornton Freeway sign also had several smaller highway markers attached to it, the same kind of markers referenced in the photograph that Holland and Rush mention.

Figure 2. R.L. Thornton sign with attached highway signs located near west end of the Depository.

But, how in the world would anyone know any of this from reading the Holland and Rush article?

Holland and Rush urge their readers to discard the assumed “illusion” that the Zapruder film depicted the assassination in full and embrace their theory that Oswald fired a shot much earlier than anyone ever thought before. But, their theory is the illusion – concocted from a half-dozen cherry-picked, eyewitness accounts that don’t hold up under even the most basic examination.

Their claim that the residual effect of embracing their theory explains why some ear-witnesses thought the last two shots were closer together in time than the first two is equally bankrupt.

Spacing of the Shots

Most students of the assassination who believe there was a lone assassin have come to the conclusion that three shots were fired at the president in the range of Zapruder frames Z155-157, 223-224, and 312.

This shooting scenario produces intervals of 3.6 to 3.8 seconds between the first and second shots, and 4.9 seconds between the second and third shots. This of course would mean that the first two shots were closer together in time (by 1.1 to 1.3 seconds) than the second and third shots.

In their article, “11 Seconds in Dallas; Not Six,” Holland and Rush argue that such a scenario “...faces an insurmountable problem. It directly contradicts the ear-witness testimony of dozens of Dealey Plaza observers, including such notables as then-Dallas mayor Earle Cabell and then-US Senator Ralph Yarborough, both of whom were experienced hunters...”

Holland and Rush explain that a “sizable majority of ear-witnesses swore that the second and third shots were bunched closer together than the first and second shots,” which works against the idea that the first shot was fired in the Z150’s. Holland and Rush contend that an earlier shot (i.e., one before Z133; the moment Zapruder began filming) solves the ear-witness contradiction. But, does it?

While it is true that a majority of ear-witnesses reported that the second and third shots were closer than the first and second, only 39% of respondents mentioned the spacing of the shots at all. Sixty-one percent didn’t mention (or were never asked about) the spacing of the shots. Of those who did, 5% thought the first two were closer together, 25% thought the last two were closer together, and 9% though the shots were evenly spaced.

One-quarter is hardly a meaningful percentage given the great pool of total ear-witnesses, but let’s assume for a moment that Holland and Rush have a point.

What is particularly devastating to the Holland and Rush thesis, and what they don’t mention in their article, is the fact the ear-witnesses who thought that the second and third shots were closer together, consistently reported that those shots were not just closer together in time but were practically on top of each other – a description that is completely at odds with Holland and Rush’s own theory.

For instance, take a look at the testimony of Earle Cabell, one of two ear-witnesses that Holland and Rush cite as supporting their theory:

“...There was a longer pause between the first and second shots than there was between the second and third shots. They were in rather rapid succession... [Asked to estimate the number of seconds between shots in the form of a ratio, Cabell replied] ...approximately 10 seconds elapsed between the first and second shots, with not more than 5 seconds having elapsed until the third one...” [7H478]

That means, according to Mayor Cabell, that the time between the second and third shots was only half as long as the time between the first two shots – a significant and easily discernable change in intervals.

And here’s the statement of Ralph Yarborough (who was sitting in the left rear seat of the Vice President’s car, two behind Kennedy), the other Holland and Rush ear-witness:

“...as the motorcade went down the slope of Elm Street toward the railroad underpass, a rifle shot was heard by me; a loud blast, close by. I have handled firearms for fifty years, and thought immediately that it was a rifle shot...After what I took to be about three seconds, another shot boomed out, and after what I took to be one-half the time between the first and second shots (calculated now, this would put the third shot about one and one-half seconds after the second shot – by my estimate – to me there seemed to be a long time between the first and second shots, a much shorter time between the second and third shots – these are my impressions that day), a third shot was fired...I heard three shots and no more. All seemed to come from my right rear...” [7H440]

That means, according to then-Senator Yarborough, that the time between the second and third shots was only half as long as the time between the first two shots – again, a significant and easily discernable change in intervals.

Here is the testimony of three more ear-witnesses who were closest to the President:

“...[describing the second and third shots] … it was like a double bang – bang-bang... You have heard the sound barrier, of a plane breaking the sound barrier, bang, bang? That is it...” [ Secret Service agent Roy Kellerman, March, 1964 - 2H76]

“...The last two seemed to be just simultaneously, one behind the other...” [Secret Service agent William Greer, March, 1964 - 2H118]

“...I heard a noise from my right rear which seemed to me to be a firecracker. I immediately looked to me right, and, in so doing, my eyes had to cross the presidential limousine and I saw President Kennedy grab at himself and lurch forward and to the left...just about as I reached [the limousine], there was another sound, which was different than the first sound. I think I described it in my statement as though someone was shooting a revolver into a hard object – it seemed to have some type of echo...it had a different sound, first of all, than the first sound that I heard. The second one had almost a double sound – as though the sound of a gun going off and the sound of the cartridge hitting the metal place, which could have been caused probably by the hard surface of the head...” [Secret Service agent Clint Hill, March, 1964 - 2H138, 144]

Do you see the problem? The Holland/Rush early-shot theory contends that 6.3 seconds elapsed between the first and second shots and 4.9 seconds elapsed between the second and third. But, how in the world do those intervals jive with the ear-witnesses that Holland and Rush cite, or with any of the ear-witnesses for that matter?

Yes, the interval proposed by Holland and Rush is in fact 1.4 seconds shorter between the second and third shots. But can we realistically expect an ear-witness to notice such a minor change in interval, given the surprise element of the attack and the total duration of the shooting? Is it reasonable to expect those ear-witnesses to describe the Holland/Rush proposed intervals as if the last two shots were fired back-to-back?

Here is an audio track consisting of the sound of an actual Mannlicher-Carcano (identical to Oswald’s rifle) being fired at the exact intervals proposed by Holland and Rush:

HOLLAND-RUSH SHOT SEQUENCE.MP3 (Z107, Z223, Z313)

This recording was sent to Holland and Rush six months ago. They were asked to comment. They never responded. There are only two questions to ask yourself as you listen:

Does the interval of the gunshots sound bunched together, as the Holland and Rush theory demands, or does it sound evenly spaced?

If you were an ear-witness to these unexpected gunshot sounds, would you report that the last two were fired closer together than the first two (or that they were practically on top of each other), or would you say they were evenly spaced?

The fact of the matter is the ear-witness accounts cited by Holland and Rush do not match the cadence of the shot sequence that they themselves propose. Period.

Is it any wonder that Holland and Rush muffed their investigation of the ear-witness accounts of the assassination – which, oddly enough, sent them in search of evidence of a much earlier first-shot to begin with? What a sham.

Position “A”

Easily one of the goofiest bits of evidence that Holland and Rush hold up as supportive of their theory is Commission Exhibit No. 885, which was labeled ‘Position A’ by the FBI.

Taken on May 24, 1964, during a re-enactment, ‘Position A’ represents the first point at which FBI agents stationed in the sixth floor sniper’s nest window of the Book Depository were able to see the chalk-marked entrance wound on the back of the presidential stand-in after the limousine had turned onto Elm Street. [Figure 3]

According to Holland and Rush, Oswald squeezed off his first shot just as Kennedy’s back became visible – as evidenced by ‘Position A’.

But Holland and Rush can’t seem to understand that the presidential limousine was never in ‘Position A’ on the day of the assassination. An FBI photograph taken at the equivalent of ‘Position A’ and made from Zapruder’s position shows the limousine at an odd angle to, and considerably north of, the middle of the center lane, which it occupied on the day of the assassination.

Figure 3. Commission Exhibit No.886 - Position "A".

The presidential limousine’s route on the day of the shooting is well documented. The path the limousine followed as it turned from Houston onto Elm Street was captured on five amateur films including the Zapruder film. Those films show that the president’s car remained in the middle of the center lane, never venturing anywhere near the position or angle depicted in the ‘Position A’ image. In short, ‘Position A’ doesn’t represent any position that the presidential limousine occupied at any time on the day of the assassination.

Sounds simple enough, right? This was pointed out to Holland and Rush by Sixth Floor Museum curator Gary Mack back in February of 2007 when Holland and Rush first proposed their theory:

“Good heavens! Did anyone review this before publication? I'm afraid you guys are going to get hammered over your Zapruder film theory...Do you not realize that the limo location in ‘Position A’ bears little resemblance to the route of the limo that day? As is very well established from the full frame (including sprocket hole area) Dorman and Towner films, the limo turned from straddling the yellow line in the middle of Houston Street into the very center of the middle lane on Elm. There was no wide swing into the north lane of Elm...”

Holland bristled at the suggestion that ‘Position A’ wasn’t important, responding:

“Whether or not the Cadillac is correctly positioned in the photo, the real issue is the description of ‘Position A’ as defined by Shaneyfelt and Frazier in their testimonies. [i.e., as the first position that Oswald had a shot at Kennedy’s back.] Moving the Cadillac doesn't change the accuracy of this definition...” [emphasis added]

Perhaps not, but why couldn’t Holland and Rush simply demonstrate that shifting the limousine into its actual position still provides Oswald with a beautiful view of Kennedy’s back? Why all the subterfuge and pretense that they have it all figured out – unless of course, they don’t?

It seems pretty obvious that Holland and Rush didn’t know that the president’s limousine was never in ‘Position A’ on November 22 and didn’t want to admit their mistake. Even so, it’s been six months since their error was pointed out to them and yet they continue to use the ‘Position A’ photograph to illustrate the position of the Kennedy limousine around the time of the first shot.

Deflected Shot?

Holland and Rush’s argument seems to assume a key fact in explaining the first missed shot – the first shot must have missed because it deflected off of something (i.e., the traffic light pole, a tree branch, etc.). Why? Why does everyone assume that Oswald’s first shot missed because it hit an intervening object? Isn’t it possible that the first shot missed because Oswald’s aim was poor?

There are a million-and-one reasons why a first shot could have been off target, as any avid hunter will tell you. It may be that Oswald simply fired prematurely. Or perhaps, Oswald intended to wait until the limousine was further down Elm Street to fire the first shot, but when the moment arrived, the target was so deliciously close that Oswald couldn’t resist and changed strategy at the last moment. We know that the first shot was the only left-to-right tracking shot in the entire shooting scenario, and one of the hardest to accomplish.

Personally, I don’t see a problem with the first shot missing simply because of the difficulty of the shot. No half-baked theories needed.

I’m afraid the Holland/Rush theory adds nothing of value to the case and only muddies the waters even further – if that’s possible.

I posted my thoughts, as detailed above, to a private email chain of which Max Holland was a member. Holland immediately responded by questioning whether I was trying to avoid a public debate about the merits of his article by posting my response privately.

Of course, the only thing I was trying to avoid was Holland's own public humiliation for writing something under the guise of journalism that was so transparently and pathetically irresponsible. I naïvely thought he might re-examine his work.

Instead Holland circled the wagons and fired back, writing:

“This current debate is not about which theory fits best with all the facts in evidence, including eyewitness and ear-witness testimonies, and extant photographs and home movies, and the possible deflection of the bullet. This is about a deeply vested position, and the fact that Dale Myers did not think outside the box, and consider, evidently, the possibility that the first shot occurred before Zapruder re-started filming.”

Similar sentiments were expressed by his co-author, Johann Rush.

What nonsense. Of course, I’ve considered the possibility that the first shot was fired before Zapruder began filming the limousine's journey down Elm Street (i.e., pre-Z133). I’ve considered a lot of possibilities (including some pretty outlandish ones) in the course of thirty-plus years of researching and examining this case. So have a lot of people.

But this is not about me, no matter how bad Holland and Rush would like to deflect criticism away from their theory. This is about evidence – credible evidence – that is presented in a truthful manner.

At the end of the day, there is no credible evidence that supports the Holland and Rush theory of an early shot – no eyewitness or ear-witness testimony, extant photographs, or home movies.

It’s one thing to think outside of the box, but when you stray from reality as far as Max Holland and Johann Rush have, one can only conclude that either Holland and Rush aren't familiar with the record or they are deliberately misleading their readers. I like to think that the former is true – they aren't familiar with the record. And while that's forgivable (hey, anyone can make a mistake), when someone who claims to be a historian of record denies the truth, well, that's just dangerous.

Hidden in Plain View

In the last month, Seattle lawyer and assassination student Kenneth R. Scearce wrote an Internet-posted article (“Hidden in Plain View: The Zapruder Film and the Shot That Missed”) that claimed to offer additional support for the Holland/Rush theory. According to Scearce, the Zapruder film itself holds long-overlooked clues that support the thesis that the first shot was fired before Zapruder began filming, just as Holland and Rush theorize.

Scearce writes that “one of the major conceptual flaws of the Z155–Z157 consensus timing is its failure to evaluate the timing of the 1st shot in light of common human experience.” His basic argument is that the 0.25 second startle response reaction time used in calculating eyewitness reactions (specifically Governor Connally’s head turn) only takes into account the subconscious reaction and not the conscious reaction to an external stimulus, like a gunshot.

As a supporting example, Scearce quotes a passage from Howard Brennan’s book, Eyewitness to History in which he describes the assassination moment:

“...When the presidential car moved just a few feet past where I was sitting, President Kennedy looked back to our side of the street. Just at that moment the whole joy and good will of the day was shattered by the sound of a shot. It took an instant to realize that something had happened. My first instinct was to disbelieve my own ears...My first thought was that it must have been a backfire. I’m sure many other people around me must have thought the same thing for there was no instantaneous reaction from the crowd...” [Brennan, Howard L.; with J. Edward Cherryholmes, Eyewitness to History, 1987, p.12-13]

Scearce doesn’t seem to pick up on the significance of Brennan’s remark that “Kennedy looked back to our side of the street” [i.e., the left side of the car] just before the first shot rang out. This, of course, relates to Zapruder frames Z140 to Z154, which means the first shot would have been fired after this point, not before, as Holland and Rush theorize. But, I digress...

Scearce notes that it took time for Brennan to react, disbelieving his own ears at first, then concludes: “...If the motorcade participants reacted like Brennan did, the physical manifestations of their reactions would have taken an appreciable amount of time to become visible from a distance as bodily movements. To be natural, their reactions would take at least 1 to 2 seconds, or more, to manifest themselves in actions like turning one’s head to look around...”

Where does Scearce come up with ‘1 to 2 seconds’ (as opposed to 3 or 4 seconds, or 0.25 seconds)? He pulls it right out of his arse. A moment later, Scearce writes: “This estimate is admittedly somewhat subjective—but the reaction time issue at hand is not amenable to exacting objectivity. It involves interpretation of conscious human action.”

Yes, yes. Mr. Scearce relies a lot on subjective interpretation to make his points. But that doesn’t get us closer to an objective truth, does it?

Scearce urges his readers to “test” his hypothesis by imaging oneself in the circumstances the motorcade participants found themselves in: utterly unprepared, like Brennan and the other onlookers, for what happened. Apparently this subjective-type test allows one to properly interpret conscious human reactions.

Scearce concludes that “common sense and life experience” dictate that motorcade participants like Connally would not have reacted by turning their heads with “near-instant, robotic speed” in the direction of the sound, but would have reacted more slowly, because like Brennan they would have been confused and uncertain.

Really? Let’s back up a moment.

First, using Howard Brennan’s reaction to the sound of gunfire as some sort of yardstick against which all others can be judged is hardly a fair and unbiased method of measuring human reaction times. Obviously, every ear-witness reaction is going to be colored by the unique set of life experiences which that particular ear-witness carried with them into Dealey Plaza. Thus, we can expect ear-witnesses who had been around firearms (or who have been in combat) to react differently and more immediately than those who had not. The testimony of many Dealey Plaza witnesses bears out this fact.

Governor John B. Connally, an avid hunter, was one of those witnesses who – unlike Howard Brennan – immediately recognized the first “noise” as a rifle shot: “...I heard this noise which I immediately took to be a rifle shot. I instinctively turned to my right because the sound seemed to come from over my right shoulder...” [emphasis added] [4H132-33]

I know that Holland, Rush, and Scearce would like to pretend Connally was a traumatized victim of the assassination and as such is completely unreliable as to what he thought and what he did at the time of the shooting. It’s also a very inconvenient truth for theorists like Holland, Rush, and Scearce to acknowledge that Connally was steadfast in his recollection throughout his life, or that it his recollection is fully supported by the filmed record (more on that in a moment).

Second, Mr. Scearce writes that the 1939 experimental work of C. Landis and W. Hunt on human reaction times in response to gunshot sounds measured subtle bodily movements, “primarily, sudden eye-blinking and slight hunching of shoulders.” This is a complete mischaracterization of their work.

Landis and Hunt’s work measured “head movement,” “movement of neck muscles,” and the “initiation of arm movement.” They found that the reaction time was 0.06 to 0.20 seconds – that is the equivalent of 1.1 to 3.7 Zapruder frames. [6HSCA28] Obviously, these are minimum time values. But they do give us an idea of how quick an individual could physically begin to react to the sound of a gunshot.

How long did it take Connally to begin his immediate and instinctive (his words) reaction to the sound of the gunshot he heard? There is really no way of knowing precisely how much time elapsed between the sound of the gunshot and the Governor’s reaction. And there is no sense guessing, as Mr. Scearce prefers to do.

However, there is a moment captured in the Zapruder film that indicates how long “immediately” might have been and it’s considerably shorter than the 1 to 2 second duration invoked by Mr. Scearce.

Head Shot Reactions

At the moment of the head shot (Z313), and in subsequent frames, we can see Governor Connally, Nellie Connally, and Secret Service agents William Greer and Roy Kellerman react to the impact of the third shot against the president’s skull by ducking their heads – an immediate and instinctively conscious act. [Figure 4] In each case, these individuals began to respond to the fatal shot by Z322 – just 9 frames (0.49 seconds) after the head shot.

Figure 4. Stabilized Zapruder film sequence - Z300-330.

While the reaction times related to the head shot involve visual as well as auditory stimulus, it is a fair measure of the speed at which human beings can react to external stimuli in general and how quick Governor Connally in particular was able to react, even after being severely wounded.

So, while no one can be sure of the exact amount of time that Connally took to begin a visible reaction to the first gunshot, his own words “immediate” and “instinctive” suggest a period very short and his reaction at the moment of the third shot certainly leaves open the very real possibility that he could have consciously reacted to the first shot in as little as 0.49 seconds; or the equivalent of nine Zapruder frames. That would put a first shot back around Z153.

Obviously, the idea that Connally would have taken 1 to 2 seconds or more to react to the sound of a gunshot is completely speculative and has no basis in fact.

A Forensic Flaw

According to Scearce, the greatest flaw in the belief that the first shot was fired in the Z150’s is that Governor Connally’s reaction beginning at Z162 was not his first reaction.Mr. Scearce claims that a right-to-left head turn made by Connally immediately before his left-to-right head turn at Z162 was actually his first reaction to the sound of gunfire. In short, Connally snapped his head to the left and then to the right – all in reaction to the sound of the first shot. This alone, according to Scearce, means that the first shot was fired before Z149 – the frame in which Connally initiates his right-to-left head snap.

This is all big news for Mr. Scearce, who believes Connally’s sudden leftward head turn at Z149 has gone unnoticed and “begging for explanation.” After declaring that the explanation is self-evident (according to Scearce, Connally’s sudden leftward head turn beginning at Z149 is his reaction to having heard the first shot), Scearce goes on to make a number of false charges about Dale Myers (yes, that’s me), namely:

(1) “...Connally’s initial leftward head turn is not shown in Myers’ computerized recreation of the Zapruder film; only his subsequent rightwards head turn is shown. Myers and the consensus timing he represents have simply failed to notice critical evidence...”

(2) “...Myers—today’s leading Zapruder film expert—rejects the Holland/Rush theory primarily because it conflicts with his own theory that Connally’s Z162 rightward head turn was Connally’s first reaction to the 1st shot...”

(3) “...Myers holds himself out as an expert on the Zapruder film on his website and on television programs watched by millions, but he has overlooked obviously important evidence in the Zapruder film, thus calling his expertise into question...”

All three of these charges are false in every respect.

First, my computer reconstruction of the assassination based on the Zapruder film does show Connally’s initial head turn at Z149 (actually the head turn begins at Z151 – more on this in a moment). This is quite evident to anyone who saw the preliminary reconstruction produced back in 1993 or who has seen the updated version first broadcast internationally in 2003 and repeated in subsequent screening many times since. I can only surmise that Mr. Scearce hasn’t seen either.

Second, I have yet to embrace the Holland/Rush theory because to date they have failed to provide any credible evidence that a shot was fired prior to Z133. I know Holland and Rush (and now, Scearce) would like to turn my criticism of their early-shot theory into a personal issue (“My theory is better than your theory”), but I’m not biting. And I believe my track record on this issue shows that my objection is and always was focused on evidence – or, the lack there of, as it were. Period.

Third, whether I am an “expert” on the Zapruder film or any other aspect of the Kennedy assassination is for others to decide. I don’t blow my own horn in that regard, as Mr. Scearce well knows. I do know a great deal about this case, to be sure. My work in some areas has led to considerable exposure on national television. If that keeps Mr. Scearce up nights, so be it. I make no apologies. His claim that my expertise should be called into question because I overlooked so-called “important evidence in the Zapruder film” has already been shown to be a cart full of road apples.

Mystery Solved

Oddly, the reasons why Mr. Scearce believes the Zapruder film supports the Holland/Rush theory are entirely subjective, and ultimately, without merit.

For instance, Scearce describes how President Kennedy, Mrs. Kennedy, and Governor Connally all turn to their left between Z140 and Z149, then turn back to their right about one second later. Both head turns – first left, then right – can only be interpreted, according to Scearce, as a reaction to a first shot fired 1.8 seconds earlier.

Scearce sees the left-then-right head turns as a single reaction to a gunshot – not two reactions to separate events occurring close in time; for instance, as one natural action (greeting the cheering crowds) interrupted by a second action (responding to a gunshot).

He rejects the notion that the initial leftward head turns can be subscribed to anything other than the sound of a gunshot – for instance, as a natural reaction to the crowd. According to Scearce, the near synchronous nature of the three head turns to the left cannot be explained innocuously; they are obviously a reaction to severe stress. And anyone who ignores those initial leftward head turns, “as the Myers/consensus timing does,” Scearce declares, is misinterpreting the evidence.

Really? Not only is Scearce’s spin on the Zapruder film subjective, it completely ignores the testimony of the limousine occupants as well as the photographic record.

For instance, Governor Connally testified that he immediately and instinctively turned to his right after hearing a rifle shot that appeared to come from over his right shoulder. [emphasis added] [4H132-33] There is nothing ambiguous about Connally’s testimony. He recalled that he turned to his right – not to his left, and then right – for a very specific reason; the shot seemed to be coming from over his right shoulder.

How does Scearce explain away the Governor’s testimony?

“We cannot expect Connally to have accurately recalled every quarter-second detail of his reaction to the shocking event,” Scearce writes, “and we therefore should not rely on Connally’s recollection that his first reaction was to turn to his right. Just as the Zapruder film refutes Connally’s unwavering and confident insistence that he was hit by a different bullet than the one that went through Kennedy’s neck, so too does it disprove the notion that Connally’s first visible head turn in the film was towards his right.”

But surely Scearce must know that this explanation is false.

First, Governor Connally has always maintained that he had time to turn to his right between the time he heard the first shot and was hit by the second shot. This is supported by the Zapruder film. The idea that the first bullet struck Kennedy in the upper-right back and emerged out of his throat comes from the testimony of Mrs. Nellie Connally – not the Governor, who has always maintained that he never saw the president once the shooting began.

The Governor assumed for many years that his wife’s recollection was accurate (he certainly didn’t contradict her), however, the Zapruder film itself refutes Mrs. Connally’s recollection, showing that she didn’t look back at the president until after her own husband was wounded, and therefore couldn’t have seen the president react to being hit until after the second shot was fired.

So, in the end, the Zapruder film does not refute Governor Connally’s recollection, as Scearce claims; it supports it.

Second, Scearce complains that Connally’s leftward head turn immediately before his turn to the right has gone unnoticed by those who believe the first shot was fired in the Z150’s. This is rather presumptuous, of course. Connally’s leftward head turn has not gone unnoticed, certainly not by this writer. In fact, a possible explanation for Connally’s left head turn is obvious to anyone who takes the time to examine the photographic record of the motorcade’s journey through Dealey Plaza. That’s something I do know a great deal about. [See: Epipolar Geometric Analysis of Amateur Films Related to Acoustics Evidence in the John F. Kennedy Assassination]

Connally’s Head Turn

Seven amateur films capture the motorcade’s progression through Dealey Plaza immediately before the shooting. Throughout those films we can see the limousine’s occupants turning to greet crowds on both sides of the street. Governor Connally can be seen turning from one side of the street to the other five times between the time the limousine enters Dealey Plaza and the shooting erupts.

In each and every case, Connally’s head turn lasts 5 or 6 frames (about 0.3 seconds) – the same length of time that Connally takes to execute his head turns in the earliest frames of the Zapruder film.

So, Connally’s initial leftward head turn beginning at Z151 is not obvious evidence of the first shot as Scearce postulates, but might just as easily represent another example of the Governor responding to crowds on both sides of the street. Mr. Scearce seems to forget that Connally and the other limousine occupants were there to greet the crowds on both sides of the street, not sitting on some stage waiting to react to Oswald’s gunfire.

One of the primary reasons that Scearce believes Connally is reacting to a gunshot at Z151 (as opposed to responding to the crowd) is the speed with which Connally’s head snaps to the left.

But Scearce miscalculates the speed of Connally’s head snap by assuming it ends at Zapruder frame Z153 – a point immediately before a splice appears in the Zapruder film. In fact, the animated frame sequence accompanying Scearce’s article (which was lifted from a French website) doesn’t indicate that two frames are missing from the sequence and hence the timing is unnatural. [Figure 5]

Figure 5. Animated Zapruder frame sequence eliminating missing frames from splice.

In reality, Connally’s head turn continues until at least Z157 (and perhaps until Z159 or Z160), [Figure 6] as determined by my computer reconstruction of the Zapruder film which found that Connally turns 68-degrees to his left between Z151 and Z161.

Figure 6. Stabilized Zapruder film sequence - Z133-208.

If we consider the filmed evidence of all of Connally’s head turns up until the Zapruder film begins, we can expect Connally’s leftward turn to consume at least five or six frames which means he’s likely turning to the left up until Zapruder frame Z156 or 157 (i.e. during the frames excised by the splice). And indeed, the angular readings obtained from the film show this is the case.

There is even some indication that this particular leftward turn is a much slower, gentler sweep to the left beginning at Z139 and picking up speed at Z151. (For instance, there is a noticeable 10-degree leftward change in head position during this period.) [Figure 7]

Figure 7. Computer reconstruction of Zapruder film sequence - Z125-241.

No matter how you look at it, whether he begins turning to his left at Z139 or Z151, the speed of Connally’s leftward head turn is in keeping with his previous head movements (as documented in other amateur films of the motorcade) and gives no indication, outside of Mr. Scearce’s fertile imagination, of being related to gunfire.

In addition to Governor Connally, Mr. Scearce cites the head movements of President Kennedy, Mrs. Kennedy, and Secret Service agent George Hickey as evidence that the first shot was fired prior to Z133.

President Kennedy, of course, was killed and consequently gave no testimony on which to gauge his actions as depicted in the Zapruder film. He is seen smiling and waving to the crowd up until he disappears behind the Stemmons Freeway sign around Z202, so it is difficult to imagine that he recognized any sound prior to that as a gunshot. The only thing one can do is speculate about what he might have heard or done and that is not the purpose of this article.

Mrs. Kennedy Reacts

As for Mrs. Kennedy, Scearce claims that her left-and-then-right head turns beginning around Z142, are supportive of the idea that a shot was fired pre-Z133, but the best Scearce can offer to back up his claim is that Mrs. Kennedy’s head turn begins around the same time as the president, Governor Connally, and Secret Service agent Hickey. Apparently we’re supposed to be so enamored by the synchronous nature of the head turns of these four individuals that we’ll ignore testimony and photographic evidence to the contrary. In the case of Mrs. Kennedy there is both testimony and photo evidence that dispels Scearce’s notion – evidence which he doesn’t bother to mention.

First, the film made by Tina Towner as the presidential limousine rounded the corner from Houston onto Elm Streets shows Mrs. Kennedy looking to the left side of the car. She is still looking left when the Zapruder film begins, 0.71 seconds after the Towner film ends.

At about Z140, Mrs. Kennedy begins to turn sharply to her left in a sweeping motion that culminates at about Z161. Why did Mrs. Kennedy turn sharply to her left at Z140? Was it the sound of a gunshot, as Scearce claims?

A photograph taken by Robert Croft tells the story. Taken at the equivalent of Zapruder frame Z161, Croft’s photograph shows Mrs. Kennedy looking into his camera. [Figure 8] My computer reconstruction of the assassination, based on the Zapruder film, confirms what is obvious from the photograph – Mrs. Kennedy turned to her left and looked at Croft.

Figure 8. Detail from photograph taken by Robert Croft.

One of the things I did during the course of my computer reconstruction project was to re-create the viewpoints of many eyewitnesses to the assassination – some by motion-tracking their head movements as recorded on film. For example, it was possible to track Mrs. Kennedy’s facial plane with a virtual camera and determine precisely what areas she was looking at as the limousine traveled through Dealey Plaza. The results show that Mrs. Kennedy turned to her left and locked onto Mr. Croft’s position until just after the photograph was taken. [Figure 9]

Figure 9. Computer reconstruction of Mrs. Kennedy's viewpoint using motion tracking.

“...You know, there is always a noise in a motorcade and there are always motorcycles besides us, a lot of them backfiring. So, I was looking to the left. I guess there was a noise, motorcycles and things. But then suddenly Governor Connally was yelling, ‘Oh, no, no, no.’ ...So, I turned to the right. And all I remember is seeing my husband, he had this sort of quizzical look on his face, and his hand was up ...[later]...there must have been two [shots] because the one that made me turn around was Governor Connally yelling. And it used to confuse me because first I remembered there were three [shots]...But I heard Governor Connally yelling and that made me turn around, and as I turned to the right my husband was doing this [indicating with hand at neck]...” [emphasis added] [5H180]

Indeed, we find support for Mrs. Kennedy’s testimony in the early frames of the Zapruder film. Beginning at Z162, Governor Connally turns sharply to his right, just as he said he did after hearing the first shot. This is the only time prior to his own wounding at Z223-224 that Connally makes such a right turn. A moment later, beginning at Z167, Mrs. Kennedy spins to her right and is looking at her husband when he and the Governor are hit by the second shot.

None of this information – neither Mrs. Kennedy’s relevant testimony (describing her actions in relation to the first shot), or the Croft photograph (which further explains Mrs. Kennedy’s actions) is mentioned by Holland, Rush, or Scearce.

Motion-tracking shows Mrs. Kennedy’s leftward head turn around Z140 is not evidence of an earlier gunshot, as Scearce suggests, but little more than the First Lady giving a camera-armed bystander the opportunity to capture a lasting memory. In addition, and more importantly, Mrs. Kennedy’s testimony dovetails with that of Governor Connally – both backed up by the Zapruder film and strongly indicative of a first shot fired in the range of Zapruder frames Z153-157 (assuming an immediate and instinctive reaction).

George Hickey Reaction

Another witness that Mr. Scearce relies on for support of an early shot is Secret Service agent George Hickey, who is riding in the left rear seat of the Secret Service follow-up car. According to Scearce, at Z143/144 Hickey looks “left and downwards at the pavement or at the tires of the vehicles, not at the crowd.”

Mr. Scearce never really explains why Hickey would look at the pavement or the tires on his left, although he suggests that the other limousine occupants were probably reacting to sound of a bullet smacking the pavement to the left of the limousine, writing:

“...The sound dynamics in the assassination environment may explain this, or the explanation may be simply that the people in question were confused. If the 1st shot ricocheted off the metal traffic light arm and hit the pavement, it could have produced a smacking sound to the left of the limousine. Or, the explanation could be a multiplicity of these and other factors.”

Or, one might add, the explanation could be none of these factors.

Obviously, Mr. Scearce doesn’t know why Hickey and the other limousine occupants turned leftward. He has no definitive evidence – testimonial or physical – to indicate why they turned leftward, and he certainly cannot explain their actions with anything other than the flimsiest speculation.

Again, Scearce pins his entire belief that Hickey’s head turn is related to gunfire and not something else on the near synchronicity of Hickey’s head movements with President Kennedy, Mrs. Kennedy, and Governor Connally.

Of course, we’ve already seen considerable evidence that the leftward head turns of Mrs. Kennedy and Governor Connally were unrelated to gunfire. Here’s what Hickey says about his own actions:

“...After a very short distance I heard a loud report which seemed like a firecracker. It appeared to come from my right and rear and seemed to me to be at ground level. I stood up and looked to my right and rear in an attempt to identify it...” [emphasis added] [George W. Hickey, Jr., Left Rear Seat, Secret Service Follow-up Car; Nov. 30, 1963 Statement; 18H762 CE1024]

So here, Hickey, as plain as day, tells us exactly what he did when he heard the first of three shots – “I stood up and looked to my right and rear in an attempt to identify it.” Nowhere does Hickey say that he looked “left and downwards at the pavement or at the tires of the vehicles” at the sound of the first shot, as Scearce interprets.

So, does the Zapruder film show Hickey taking the actions he described? It sure does.

Figure 10. Stabilized Zapruder film sequence - Z133-251.

Between Zapruder frames Z193 and Z200 (0.38 seconds) we see Hickey, who has been looking left, suddenly snap his head to his right-forward; then begin to straighten his back and turn sharply to his right-rear until he disappears into the margins of the film frame at Z213. [Figure 10] All of this occurs in 1.1 seconds, beginning at Z193, and matches Hickey’s testimony regarding the actions he took immediately after the first shot. By the time the James W. Altgens photograph [Figure 11] was made 2.3 seconds later (the equivalent of Zapruder frame Z255), Hickey had turned completely to his right rear.

Figure 11. Detail from photograph taken by James Altgens showing Hickey (arrow) and other agents.

So once again, testimonial and photographic evidence demonstrates that the actions of George Hickey as seen in the Zapruder film, and interpreted by Mr. Scearce as being related to gunfire, are in fact apparently unrelated to the shots fired at the President.

Want more testimonial and photograph evidence that the first shot was likely fired later than Holland, Rush, and Scearce theorize?

Here’s agent John Ready, standing on the right front running board of the Secret Service Follow-up Car:

“...we began the approach to the Thornton Freeway traveling about 20-25 MPH in a slight incline...I heard what appeared to be firecrackers going off from my position. I immediately turned to my right rear trying to locate the source but was not able to determine the exact location...” [John D. Ready, Right Front Running Board, Secret Service Follow-up Car; Undated Statement; 18H749 CE1024]

Turning to the Zapruder film, we see agent Ready scanning the left-front area of the procession. Between Zapruder frames Z176 and Z184 (0.44 seconds), Ready’s head snaps to his right front; then pulls his hand off the windshield trim (Z197) and rotates his entire body to the right until he disappears from view at Z209.

And here’s the testimony of agent Paul Landis, standing immediately behind Ready on the same right-side running board:

“...the President’s car and the Follow-up car had just completed their turns and both were straightening out. At this moment I heard what sounded like the report of a high-powered rifle from behind me, over my right shoulder. When I heard the sound there was no question in my mind what it was. My first glance was at the President, as I was practically looking in his direction anyway. I saw him moving in a manner which I thought was to look in the direction of the sound...” [Paul E. Landis, Right Rear Running Board, Secret Service Follow-up Car; Nov. 30, 1963 Statement; 18H754-55 CE1024]

Again, turning to the Zapruder film, we see agent Landis looking forward toward the President’s car as the Zapruder film begins. We see Kennedy turn sharply to his right at Zapruder frames Z157 to Z165 – the direction everyone believed the sound came from. Between Zapruder frames Z176 and Z184 (0.44 seconds), Landis’s head snaps to his right; and he continues looking right until he disappears from view at Z208.

You’ll note that the Landis’ reaction is simultaneous with Ready’s. You’ll also note that Landis connected President Kennedy’s abrupt head snap to the right at Zapruder frames Z157-165 with the sound of the first shot, believing that the President was responding to the gunshot. This is indirect and somewhat ambiguous, but nonetheless an indication at least that Kennedy’s movements at that time might have been a response to a gunshot and not just a response to the nearby crowds.

So here we have photographic evidence of three Secret Service agents reacting within one-second of each other (two of them simultaneously) to the sound of the first shot. One of those agents believed (right or wrong) that President Kennedy was also responding to the sound of the shot when Kennedy turned sharply to his right beginning at Z157.

By contrast, none of the testimony or images presented by Holland, Rush, or Scearce indicate a first shot fired 1.4 seconds before Zapruder even began filming. Mr. Scearce concludes:

“...the Myers/consensus timing [of a shot fired in the Z150’s] stands or falls on the accuracy of Connally’s recollection of the direction in which he first turned his head after hearing the 1st shot...”

This is patently false, of course. The idea that a shot was fired around the Z150’s is based, as you’ve already seen, on a comprehensive correlation of evidence – eyewitness testimony, still images, amateur motion picture films, and computer analysis – of which Connally’s recollection (as strong, supportive, and impressive as it is) is only one small part. It is the tightness of the weave of this fabric of evidential truth that is particularly convincing.

Missing the Boat

Mr. Scearce claims to know why an army of amateur sleuths have missed what he believes are obvious signs of a much earlier shot being fired. It’s all about the “psychodynamics” of viewing the Zapruder film, according to Scearce.

Apparently, everyone has been so enthralled with watching Kennedy and Connally getting gunned down (in particular, the spectacular head shot) that they never bothered to examine the less shocking portions of the film.

And even when they did begin to examine the earlier parts of the film, they “...pursued these hints clumsily, under-appreciating again and again the Zapruder film’s full forensic value,” Mr. Scearce tells us.

Enter Gerald Posner, Vincent Bugliosi, and Dale Myers (that’s me) who, according to Scearce, have “merely adopted the theories of lesser-known researchers and woven them into well-articulated and comprehensive explanations of the film” rather than offer their own “innovative analysis of the Zapruder film.”

According to the lawyer from Seattle, these “three eminent researchers” have actually frustrated the real search for a first shot outside of their Z150-range consensus and have become a “millstone” around the necks of those really interested in the truth, leading Mr. Scearce to conclude, “...Once insightful dissenters, Myers and others who adhere to the consensus timing of the 1st shot now represent a tired ancien regime of JFK assassination research. They are being left behind by others willing and intellectually able to question old assumptions and to ask new questions.”

“The torch has been passed to original thinkers like Holland and Rush,” Mr. Scearce assures us. “They are helping uncover what has been ‘hidden in plain view’ for over four decades. The open-minded among us owe them a fair hearing in their journey through the heretofore undiscovered country of the Kennedy assassination towards the final truth.”

The final truth, eh? Mr. Scearce seems bent on trying to turn my criticism of the Holland/Rush theory of an early shot into something personal. It isn’t. It isn’t some war between the old guard and a group of so-called “open-minded thinkers,” either. And it isn’t about protecting one’s interests (not for me, anyway). It’s about one thing, and one thing only – evidence.

Where is the evidence for an early shot? I’m talking about real evidence, the kind that stands up under the most basic scrutiny? Holland, Rush, and now Scearce, have yet to offer one shred of credible evidence that supports their thesis. Instead, we get The Amateur Hour.

When confronted with their own appalling lack of credible evidence and genuine ignorance about many key aspects of the case that relate directly to their own theory, Holland, Rush, and now Scearce, claim the critics of their theory are the ones with a vested interest to protect. Yea, sure.

Evidence, gents. That’s what it’s all about. That’s all it has ever been about. Show us the evidence that supports your theory.

So far, from where I stand, Holland, Rush and Scearce have failed completely in that regard. Déjà vu.

This is the second time in six months that the Holland and Rush early-shot theory has generated national press. It would be nice to see these new progressive thinkers, who are so “willing and intellectually able to question old assumptions and to ask new questions,” actually come up with some credible evidence to support their “final truth.”

I don't think that's too much to ask.

END

Flash 8 or higher is required to view videos accompanying this article. Get the free plugin now.

A theory that Lee Harvey Oswald fired his first shot earlier than anyone had ever considered before is making the rounds again. But despite the accolades from uninformed circles, the theory has proven, once again, to have no factual basis. I say ‘once again,’ because we’ve heard all of this before. Déjà vu.

In their article “J.F.K.’s Death, Re-Framed,” published as a New York Times Op-Ed piece on the forty-fourth anniversary of the Kennedy assassination, Max Holland and Johann W. Rush propose once again that Oswald fired his first shot nearly three seconds earlier than previously thought and that this first shot struck a traffic pole resulting in a ricochet that missed the motorcade.

According to Holland and Rush, their theory is supported by eye and ear-witnesses to the shooting (including Amos L. Euins, the only one named in the New York Times article) and explains why Oswald missed his first and closest shot.

“Oswald still did it,” Holland and Rush assure us, but their new theory, they say, could have saved the Warren Commission from falling into disrepute because it offers a shooting sequence that is far more plausible in its timing.

New theories abound in the Kennedy assassination. In fact, we’re awash every November in new theories about what happened in Dallas. Most of these new theories are a lot of nonsense.

But, when the New York Times publishes a piece by someone like Max Holland (author of “The Kennedy Assassination Tapes,” and a forthcoming book on the Warren Commission) and Johann Rush (a television photographer, who filmed Lee Harvey Oswald demonstrating in New Orleans in August 1963) people sit up and take notice.

One expects to read a factual, accurate, and well-researched take on this very controversial subject in such a prestigious venue. Instead, Holland and Rush stumble their way through an embarrassing, ill-conceived, unsupportable theory that comes off more like ‘headline grabbing’ than anything else. What a shame.

None of this is new, of course.

Holland and Rush first floated their early-shot theory back in February, 2007, in an article entitled “1963: 11 Seconds in Dallas,” which was published on the Internet’s History News Network (HNN). Their claim that the new theory was supported by the historic record was quickly criticized for being false and misleading. [See: “Max Holland’s 11 Seconds in Dallas”] Their reaction to the criticism was to defend the indefensible and charge that those who were critical of their theory were only doing so in an effort to cover-up their own inadequate theories.

Their recent Op-Ed piece in the New York Times, and a subsequent article by Seattle lawyer Kenneth R. Scearce, posted on the John McAdams’ website The Kennedy Assassination, is nothing but a rehash of the same old, unsubstantiated claims.

Despite all of their foot-stomping, Holland and Rush cannot escape the simple truth that their theory has no support whatsoever in the historic record. They might just as well have pulled their thesis out of thin air. They started with a false premise, based on a generalization of the ear-witness accounts which described the spacing of the shots, then backward engineered “evidence” of an earlier first shot from a carefully chosen selection of eye witness accounts, all of which fail to pass a basic litmus test. When they were called out on it, they refused to acknowledge the obvious – they blew it. What a disappointment.

Back in June, I mused, “Let’s hope that any future writings from Max Holland and Johann Rush have more bite than sizzle to them.”

Apparently, the pair didn’t feel it was necessary to revise their claim and plowed forward as if nothing had happened. With only a few minor alterations, Holland and Rush foisted the same, fatally flawed theory on the unsuspecting editors and readers of the New York Times.

Nowhere in their November Times Op-Ed piece (or in their companion article, “11 Seconds in Dallas; Not Six,” now posted on Holland’s ‘washingtondecoded.com’ website) do Holland and Rush address or respond to the multitude of factual inaccuracies pointed out about their early-shot thesis back in June. Apparently they are content to look the other way and pretend their investigative and journalistic skills pass muster.

Most of what follows was covered six months ago in an article that you’ll find archived on this website. [See: June, 2007 – “Max Holland’s 11 Seconds in Dallas”] For those of you just getting up to speed, here’s the heart of their argument and the truth about their claims.

First, you should understand that this discussion is all about the timing of the first of three shots fired at the presidential motorcade. Holland and Rush’s theory is not a conspiracy theory. They are convinced Oswald did the shooting alone. Their theory purports to answer one key question about the assassination:

How did Oswald managed to miss his closest and therefore, presumably, his easiest shot?

According to Holland and Rush, the answer to that question also has the residual effect of answering two additional questions:

Why did numerous ear-witnesses think the last two shots were bunched closer together?

The Shot That Missed

Practically everyone who has studied the assassination and who believes there was a lone assassin agrees today that of the three bullets fired that day, it was most likely the first bullet that missed the motorcade – the next two bullets striking Kennedy and Connally. There, however, the agreement ends.

The general consensus has been that the first shot was fired immediately prior to Z160, based largely on the actions of Governor Connally and Mrs. Kennedy who seem to be reacting to the first shot in subsequent frames.

Many believe Oswald’s first shot struck the branch of an intervening oak tree and was deflected, missing the limousine entirely.

Others, like Reclaiming History author and renowned prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, noted that Oswald’s first and closest shot was also the most difficult shot of the three – a tracking shot, moving left to right. The last two shots were fired while the limousine was moving directly away from and on a slight incline from the sniper’s firing position, a fact which made Oswald’s target virtually stationary.

Still others suggest that Oswald simply ‘botched it’ – his missed shot attributed to ‘buck fever,’ a term familiar to deer hunters everywhere.

According to Holland and Rush, all of these speculative offerings are wrong. It is their contention that Oswald fired several seconds earlier than anyone had ever considered before and that the intervening object was not an oak tree but a traffic light pole that extended out over Elm Street directly in front of the main entrance of the Texas School Book Depository.

In fact, Oswald’s first shot was fired so early, say Holland and Rush, that Abraham Zapruder hadn’t even begun taking pictures with his 8mm movie camera.

What evidence do Holland and Rush offer to support their theory? It turns out their theory is based on a potpourri of false and misleading statements, twisted logic, nonsensical assertions.

For instance, when Holland and Rush first floated their theory in mid-February, 2007, they cited the testimony of seven witnesses who they claimed supported their theory that the presidential limousine had just passed the traffic light pole at Elm and Houston when the first shot was fired.

Howard Brennan

One of those witnesses was Howard Brennan, the Dallas construction worker who was seated on a concrete wall directly across the street from the Book Depository. More importantly, Brennan was seated almost directly across from the traffic light pole that Holland and Rush believe deflected Oswald’s first shot.

Holland and Rush quote this portion of Howard Brennan’s Warren Commission testimony, taken four months after the slaying, “And after the president had passed my position, I really couldn’t say how many feet or how far, a short distance I would say, I heard this crack that I positively thought was a backfire.” [3H143]