The truth about claims she witnessed the shooting on Tenth Street

|

Doris E. Holan as a young girl. (Graphic: © 2020 Dale K. Myers. All Rights Reserved)

By DALE K. MYERS

UPDATED: MARCH 10, 2024

[Editor’s Note: The following article is an updated version of the original published on November 19, 2020. Additional information was brought to my attention regarding the Holan family's residency on Tenth Street resulting in additional interviews and research. The updated article below, published on June 4, 2021, and revised again on March 10, 2024, confirms the original thesis and further undermines the claims attributed to Mrs. Holan.]

A seven-month investigation into the claims of alleged Tippit shooting witness Doris E. Holan demonstrates that the now deceased Oak Cliff resident didn’t lived on Tenth Street on November 22, 1963, and therefore, couldn’t possibly have seen what has been attributed to her by a cabal of conspiracy theorists bent on exonerating Lee Harvey Oswald for the murder of Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit.

For the better part of sixteen-years, retired Southern Methodist University professor William J. “Bill” Pulte and Dallas researcher Michael G. Brownlow have claimed that Holan told them that two Dallas police officers were present at 404 E. Tenth when Tippit was murdered.

Since first published in Harrison E. Livingstone’s 2004 book, The Radical Right and the Murder of John F. Kennedy: Stunning Evidence in the Assassination of the President, the Doris Holan story has circled the globe, thanks to the Internet, with generous additions to her tale courtesy of conspiracy theorist John Armstrong.

Armstrong now claims in his latest version of the Tippit shooting that Dallas Police Captain W.R. Westbrook and Reserve Sergeant Kenneth H. Croy were the two men seen by Holan and that Westbrook ordered an Oswald-look-a-like to dispatch Tippit to the netherworld with a fatal head shot.

Conveniently, Westbrook, Croy and Holan are all deceased which provides considerable cover for the truth-spinners.

There have been a lot of tall-tales written about the murder of Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit, killed fifty-seven years ago this week, but none more outrageous than the claims attributed to Holan.

Had anyone bothered to fact-check any of these deplorable claims, they would have found what I did during the course of a seven-month investigation I launched in early January of this year.

Herein are the results of my probe – further proof of the extent to which some so-called researchers will go to sell a dubious narrative with lies and deceptions.

Doris E. Holan

Doris Emma Middleton was born on Wednesday, June 23, 1920, in Denton, Texas to Olin W. Middleton (1895-1971) and Augusta E. “Gussie” James (1894-1970). [1]

Doris had one sibling – Laura Elizabeth “Betty Jo” Middleton. Laura was the second of twins born on January 23, 1925, in Denton, Texas. The first twin born did not survive. [2]

Laura married Air Force Master Staff Sergeant Wendell D. Ray (1928-2011) in 1953. [3] Her husband was stationed at Laughlin Air Force Base near Del Rio, Texas. The couple took up residence in the old Abb Rose home, a classical dwelling that had been a Del Rio landmark for many years before being converted into apartments in the mid-1950s.

At 2:30 a.m., in the early morning of Sunday, August 31, 1958, a fire that began in the Ray apartment swept through the complex. A mother and her three children in an adjoining second-story apartment awoke to Mrs. Ray’s screams and managed to escape. So did Sergeant Wendell Ray, who tried to re-enter the building to rescue his wife, Laura, but was restrained by fireman. Fireman doused the flames and recovered Mrs. Ray who was declared D.O.A. at the air base hospital. Mr. Ray was treated for shock. Laura was buried under the name “Betty Jo” Ray at Roselawn Cemetery in Denton, Texas. [4]

First marriage

Doris attended Denton High School and graduated on January 29, 1937, delivering the farewell address. [5]

Shortly after graduation, Doris married Gordon Elmo Sides (1918-1994). Doris was 17 and Gordon was 19-years-old. [6]

Doris gave birth to two sons: Curtis Alden Sides (1937-2017) and Lee Gordon Sides (1939-1994). The April 1940 Census shows Doris and her sons were living with her parents in Port Lavaca, Calhoun Co., Texas. [7]

In October 1940, Gordon registered for the WWII draft. At the time he was working at Standard Dredging Co., Palacios, Matagorda, Texas. Two years later, in August, 1942, Gordon enlisted in the US Navy.

Sometime during this period, his marriage to Doris ended.

Second marriage

In 1945, Doris E. (Middleton) Sides married Ladislov “Lad” August Holan (1920-2006). No marriage record could be located, although it was likely in San Diego, California. They were both 25-years-old.

“Lad” was the son of John Frank Holan (1886-1964) and Mary J. Kana (1896-1981) and was born at August 26, 1920, in LaGrange, Texas. [8]

During the war, Lad Holan was employed at the parts plant of Consolidated Aircraft Corp., in San Diego, CA. [9]

Lad and Doris had four children – two boys and two girls.

In the late 1940s, the Holan family moved to Houston, Harris Co., Texas. By the fall of 1955, the Holans had settled in Fort Worth where Lad was employed at Commercial Tooling as a tool & die maker. [10]

Trouble began to emerge in the Holan marriage in the mid-1950s.

In 1956, Lad and Doris Holan took their two boys to live with his parents, John and Mary Holan, in Fayette Co., Texas. The oldest of the two, Lad, Jr., was enrolled in a small school there and attended for one year. [11]

The Holan marriage was floundering by the time the youngest child, a daughter, was born in August of 1957.

“I was an attempt to save the marriage and it didn’t work,” the youngest daughter told me. [12]

By 1959, Lad and Doris Holan were separated (their divorce wouldn’t be final until 1960). Doris, at 37, had her hands full with four kids, ages 14, 9, 6, and 2. Trying to work full time and care for her kids pushed the envelope of what was possible for her.

She made arrangements to have her parents, Olin and Gussie, care for the youngest daughter, age 2, at their home in Terrell, Texas. [13] It helped some, but Doris still had two young boys and a teenage daughter to handle. Her jobs in the service industry barely allowed her and her kids to make ends meet. She turned to alcohol to get through it all. It soon became a problem.

Her inability to meet lease payments, coupled with problems due to alcohol, led to frequent moves, nearly every year – none of them in the best of neighborhoods.

Her son, Lad A. Holan, Jr., later told me that his family moved every year or so because his mother was an alcoholic and had issues that people weren’t very tolerant of at the time. “We hardly got our leases renewed – every year. We were always moving.” Her boyfriend and drinking partner, “Bill”, was also verbally abusive to his mother. [14]

The tough neighborhoods began affecting her two young boys. They found themselves trying to dodge trouble and keep their nose clean.

Lad, Jr., had already been in trouble with the law. While living in Mesquite, Texas, in 1957, he got into trouble chopping down trees in the city park. He said that when he was seven-years-old, he and another boy used bayonets brought home from the Korean war by his two older brothers (who served in Korea as U.S. Marines), to chop down several Cottonwood tree saplings in the city park and transplant them in a neighbor’s yard. Police were called and Lad, crying, was taken to the police station under the watchful eye of his family, so as to teach him a lesson. “They scared the hell out of me, you know?” [15]

When Doris moved to Oak Cliff in 1963, there was a lot of “meanness” on the streets, according to her son, Lad. The area was crime ridden and you had to be careful as a kid and look out for yourself. [16]

Tenth Street residence

The Holan family’s first residence in central Oak Cliff was a second-floor apartment at 409 E. Tenth, located in the third house east of the intersection of Patton Avenue. [17]

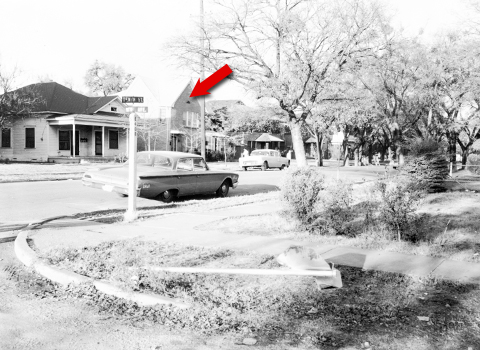

|

Fig.1 - Dallas police crime scene photograph depicting the building at 409 E. Tenth (red arrow), identified by Lad Holan, Jr., as the location of the Holan family's first apartment in central Oak Cliff.

“The people that owned it lived downstairs,” Lad told me. [18] “The whole upstairs was the apartment. The kitchen was directly to the back and – ah – two bedrooms at that time, they were left and right.” [19] The three windows on the front face of the second story were looking out from the living room in their apartment.

Lad Holan recalled that it was an “older married couple” [20] that owned the building and lived on the lower floor. He mostly remembered the woman. She was an “older gal”, Lad said. [21] “I don’t remember much else about them. We really weren’t there too long.” [22]

Dallas city directory listings show that the house was owned by Mrs. Myrtle House, the widow of Samuel E. House, a grocery market manager who died in February 1957. [23]

The house was divided into two apartments – 409 E. Tenth Street (the upstairs apartment) and 411 E. Tenth Street (the downstairs apartment). Mrs. House, age 64, lived downstairs with her son, age 33, beginning in late 1957. She died on December 20, 1963, at Methodist Hospital at the age of 70. [24]

Ownership of the house at 411 E. Tenth Street then fell to her 39-year-old son, Samuel E. House, Jr., and his wife Pat. They continued to live there through 1996. [25]

When told that Samuel E. House, Jr., and his wife Pat, both in their early forties, operated the house after Samuel’s mother Myrtle died in December 1963 at age 70, Lad Holan stated, “That’s who it was (referring to Samuel and Pat). That’s more like the age I remember.” [26]

Lad Holan’s recollection that Samuel and Pat House, and not the elderly widow Myrtle House, were operating the apartment at 409 E. Tenth at the time the Holan family lived there, seemed to support Lad’s recollection that the Doris Holan family didn’t move to Tenth Street until 1964 – after the Tippit shooting.

However, following the initial publication of this article, it came to my attention that the 1963 Cole’s Criss-Cross Cross Reference Directory for Greater Dallas, published on July 25, 1963, and providing information on the residency of citizens in the fall of 1962, showed Doris Holan already living at 409 E. Tenth in 1962. [27]

In an effort to reconcile the difference between the contemporary record and Lad Holan, Jr.’s nearly sixty-year-old recollections, I contacted Holan in early 2021 and questioned him further about the family apartment at 409 E. Tenth.

Holan offered additional details, telling me that he remembered Samuel E. House, Jr., the son of the owner of the house, “because he was the one that took care of the yard and everything.” [28]

He also remembered the owner of the house, the widow Mrs. Myrtle House, still being alive. “She had a garden in the back that we weren’t allowed to get near,” Lad said. “But I remember her living there and always sitting in the screened-in porch on the front of the house, listening to the radio.” [29]

These additional details are supported by the Cole Directory listing, which show the Holan family living at 409 E. Tenth Street in the fall of 1962 (not 1963), while Mrs. Myrtle House was still alive.

Asked if he would defer to the contemporary published record as to when the family lived at 409 E. Tenth, Holan laughed and said, “Yeah, I would do that. Why would anybody dispute the written record?” [30]

Patton Avenue residence

By September 1963, the Holan family moved to their second residence in central Oak Cliff – an apartment in a two-story, red brick building at 113 S. Patton Avenue, located adjacent to the alley between E. Tenth Street and E. Jefferson Boulevard. [31]

|

Fig.2 - The Holan family second-floor apartment (red arrow) at 113 S. Patton Avenue.

Their second-floor apartment (113 ½ S. Patton Avenue) was accessible from an entrance door located at the center of the east face of the building. The entrance door led to a staircase that rose to the second-floor. There were two apartments upstairs.

The Holan family apartment was located on the north side of the building, facing Tenth Street. A fire escape can be seen in numerous photos depicting the north side of the building, however, Holan told me that the fire escape terminated at a boarded window on the second floor and was not accessible as an escape.

Holan said that the entire first floor was occupied by an upholstery shop, later identified from Dallas City Directory listings as Garrett’s Custom Upholstery Shop. The owner, Ray Edwin Garrett (1920-1981), operated the shop out of the Patton address between 1961-1964. [32]

Living with Doris there were three of her children – Lad, Jr. and his younger brother and sister. [33]

All three kids were enrolled at Blessed Sacrament School, 201 N. Marsalis Avenue, near the corner of Eighth Street. The parochial school was adjacent to Blessed Sacrament Church, 231 N. Marsalis Avenue.

Lad, 13, was in fifth-grade; his younger brother, 10, was in fourth-grade, and his youngest sister, 6, in first-grade. [34]

Lad became an altar boy at the church and was befriended by Father Michael V. McLane, a parish priest who had gained a sizeable reputation for helping troubled youths.

Father Michael McLane

Born Newton Vaness McLane, Jr., in 1923, Father McLane was a native of Dallas, but was reared in Wichita Falls. Prior to entering the seminary, he spent four years in the U.S. Air Force during WWII and held the rank of lieutenant when he was discharged. He studied for the priesthood at St. John’s Seminary in San Antonio and Maryknoll Foreign Missions in New York. He was ordained May 26, 1956, and initially held the position of assistant pastor at St. George Church in Fort Worth. [35] He subsequently served in Tyler and Longview before being assigned in 1961 as the assistant pastor at St. Edward’s Catholic Church, 4007 Elm, Dallas, Texas. [36]

Church records show that Father McLane was assigned to St. Edward’s Catholic Church from 1962-1966, but spend much of his time speaking to and working with youths at various Catholic churches throughout the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

“He’s the one who really helped me,” Lad, Jr., told me. “Just being a friend.” [37] Lad had become an angry young boy and ‘Father Michael’, as he called him, was instrumental in straightening him out. Lad said that Father Michael was a big part of his life, and even gave him a St. Christopher medal which he kept for many years.

|

Fig.3 - Lad A. Holan, Jr., in 1970 (left), and Rev. Michael V. McLane in 1956 (right).

“I think at that point, the good Lord put him there for that reason, you know?” Lad said. “I’ll always believe that.” [38]

Lad Holan recalled that Father Michael was living in the rectory with Monsignor Paul Charcut, the pastor of Blessed Sacrament Church. [39]

Verification for Lad Holan’s claim was located in a March, 1964, article which identified Father Michael V. McLane as the assistant pastor of Blessed Sacrament Church, working alongside pastor, Monsignor Paul Charcut. [40]

Odd jobs

Doris Holan was working as a waitress at the Marriott Motor Hotel, 2101 Stemmons Freeway (across from the Trade Mart), Dallas, Texas, at that time – a job she held, according to city directory listings, for three years (1962-64). [41] She often worked afternoons, and sometimes the graveyard shift (all night).

She was often gone to work by the time her kids got home from school.

“I remember coming home and nobody was there,” Lad told me. “And I remember sometimes there would be a note there with a couple dollars on it for us to get some bread and, you know, butter, or bread and cereal or milk – whatever we needed.” [42]

Today, there might be a caregiver, a babysitter, or someone hired to watch the kids, but in those days, nobody had any money for such things.

“Nobody cared,” Lad told me. “That’s the reason why the church was important to me at that time, I guess. It was kind of my adolescent escape.” [43]

At age 13, Lad Holan, Jr., took it upon himself to help the family out where he could. He got odd jobs working after school, at nights and on weekends at Oak Cliff Lanes, a bowling alley at 309 E. Jefferson Blvd., where he was a pin-setter and swept floors. He also worked at Dean’s Dairy Way, a convenience store at 409 E. Jefferson Blvd., where he stocked groceries, filled soda-pop bottle racks, and swept floors. [44]

|

Fig.4 - Dean's Dairy Way, 409 E. Jefferson Blvd., on Nov. 23, 1963. (WBAP-TV)

Lad recalled that the owner was Firman Dean and that he worked with Firman, his wife “Dodie”, and an older fellow nicknamed ‘Doc’. [45]

Lad told me that he would always go to Dean’s Dairy Way on Saturday because the owner would pay him and another boy with cash money instead of food like ‘Doc’ would for their work at the store.

Lad said it was always competitive, to see which boy would work the hardest and get paid the most. Lad also recalled that the Dean’s – Firman and his wife “Dodie” – once invited Lad to spend the day at their home and treated him to dinner, which Lad remembered as a great kindness. [46]

Lad said that he used the alley next to their Patton Avenue apartment to get to and from his jobs at Dean’s Dairy Way and the Oak Cliff Lanes, largely because of a group of kids that lived near the northwest corner of Patton and Jefferson. They used to tease and harass him. [47]

|

Fig.5 - View looking west along the alley next to the Holan apartment (right).

“They were just a bunch of little punks and stuff,” Lad said. “I use to avoid any trouble. So, that’s the reason I went down the alley all the time. That was also the alley that went straight down to the bowling alley. And I would come out of the back of the bowling alley and come home.” [48]

“I was living in a very traumatic, troubled time,” Lad told me. “Not only for me and my little brother and my sister, but trying to help, you know? I worked at these places to help put cereal on the table for my sister and brother to eat and stuff like that. I did that, just because it needed to be done.” [49]

Lad Holan had another trick up his sleeve to make extra money. It also led to him seeing his first dead body, at age thirteen.

“You know how people would leave change in phone booths?” Lad said. “I used to take a little bit of toilet paper and stick it up in the change holder so the change wouldn’t come out, until you pull that paper out. I use to get three or four dollars a night at five or six places. And this one particular phone booth, down the street from [Dean’s Dairy Way] that I worked at – it was my hot spot. I mean, it was a good one. And one night, we closed up [at Dean’s Dairy Way], ‘Doc’ had gone home – we closed the store and I was walking – I was going to check my phone booth, right? Well, I saw this guy standing there in the phone booth. And the closer I got – [I could see] he was leaning. And then I realized there was no light on. You know how when you were standing in a phone booth and you’d close the door and the light would come on? Well, the light wasn’t on. Because it had all been shot out. He had been shot full of holes, standing there. So, that was the first dead guy I saw actually, you know, at that age.” [50]

It wouldn’t be the last dead body Lad Holan saw.

November 22, 1963

Lad, Jr., remembered that it rained hard the night before the president’s visit to Dallas. “We had thunderstorms that night,” Lad recalled, “because I thought, ‘I’ve got to walk to church in the morning’, you know, but it wasn’t raining.” [51]

Lad served as an altar boy at the 6:30 a.m. mass at Blessed Sacrament Church that morning. Father Michael V. McLane was the celebrant. [52]

|

Fig.6 - Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church, 231 N. Marsalis, Dallas, Texas.

After services, his father, Lad A. Holan, Sr., came to the school and invited his son to go downtown with him to see the Presidential motorcade. They took up a position in front of the Dallas County Criminal Courts Building, facing Main Street, standing just east of Houston Street. [53]

After the president’s limo passed them and turned north onto Houston Street, they began walking back to their truck parked some blocks away and heard about the shooting from passersby. Lad did not recall hearing any shots. His father drove him back to school and dropped him off. [54]

When they arrived at the church grounds, Lad learned that the school was about to be let out and that all students were going into the church to pray. (His sister, recalled that “for hours the nuns cried and students prayed.”) Instead of going into the church with the rest of the school children, Lad jetted out the back door of the church and walked home, taking his usual route: south on Lansing Street to Tenth, then west on Tenth to Patton, then south on Patton to his home at 113 S. Patton. [55]

|

Fig.7 - Aerial diagram showing Lad Holan's route (blue) to the Tippit scene. (Graphic: © 2020 DKM)

The Tippit shooting

As he walked west on Tenth Street toward Patton, he saw a police car in the street up ahead. “Anytime a police car stopped in our neighborhood,” Lad recalled, “there had to be something bad going on.” [56]

When he got closer, he saw that a Dallas police officer was lying in the street next to the police car. He ran up to the car, not knowing what had happened. The squad car door was open and the police radio was blaring, but the car wasn’t running. Tippit was still bleeding when he arrived. [57] Three to six people were rushing about in a panic – a couple of black women and two or three white women. They were saying, ‘Man, he’s dead!’ One woman was saying, ‘What the heck? Why would someone kill a cop?’ [58]

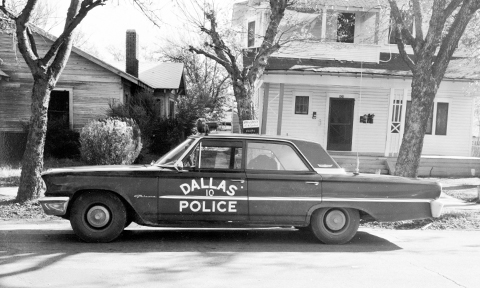

|

Fig.8 - Dallas police crime scene photograph of Tippit's squad car.

Just as he arrived a woman came out of the house on the southeast corner of Tenth and Patton and stated that she had just called the police. [59]

A teenage girl was crying uncontrollably. Lad remembered that she lived nearby and recalled that her boyfriends had motorcycles. [60] Lad stated that he repeatedly told the girl, ‘Don’t look at him. Just stop looking at him.’ Lad spotted an ‘old torn up blanket’ on a sofa sitting on the porch of one of the houses on the south side of the street. He turned to a woman who was there and asked, ‘Can I get that blanket off that [sofa] to cover him up?’ The woman said it was alright and Lad and another girl got the blanket off the sofa and covered up the officer. ‘He was a mess,’ Lad remembered. [61]

Within seconds of covering the officer with a blanket, an ambulance arrived. The first police car to arrive at the scene pulled up immediately after the ambulance. [62]

As soon as the first police car arrived, Lad Holan left the scene and went home. [63] Having been in trouble with the police before, he was afraid to stick around. He went to the family apartment on Patton, but nobody was there. So, he returned to the southwest corner of Tenth and Patton and stood under a large tree (visible in numerous crime scene photographs) and watched the police investigation from a distance. [64]

|

Fig.9 - 1964 FBI photograph looking west from Tippit's squad car location. Tree in background (red arrow) is where Lad Holan, Jr. watched police activity from on Nov. 22, 1963.

A couple of the older neighborhood ladies were standing with him. He knew them because they were on his newspaper route as a ‘paper boy’. One was crying. Another one was talking about the president being assassinated. By then, four or five police cars had arrived. [65]

Days of turmoil

Lad told me that “Oak Cliff was torn up with police for days and days and days after this happened. You couldn’t do nothing. You know? There were cops everywhere and – and I guess Secret Service people. I don’t know who they were. But there was a lot of police activity for days in that neighborhood. Every time you went outside, there was – you’d turn the corner and there’d be a policeman there or another car sitting there or – you know?” [66]

Lad recalled that at some point in time (perhaps in the days that followed), “somebody was asking if we saw them chasing Oswald. But no, we didn’t see anybody chase Oswald.” Lad told me that someone said, “Somebody stole his [Tippit’s] gun.”

Holan was questioned extensively about whether he heard that comment that day, while at the scene, or at a later date. When I suggested that the sequence of events would indicate that he would have to have lingered longer at the scene than he had said previously in order to hear that conversation that day, Holan insisted that he left immediately after the first officer arrived.

Nothing further was developed about Tippit’s gun being stolen (no doubt a reference to Ted Callaway’s subsequent actions). Asked if anything was found around Tippit’s body, Holan said, no. Asked specifically about a wallet being found, Holan said, no. Asked if he saw anyone using the police car radio while he was at the scene, Holan said, no. [67]

|

Fig.10 - Lad Holan, Jr., recognized Carl (left) and Bill Smith (right), seen in this detail from a Dallas police crime scene photograph, as brothers from the neighborhood.

Lad Holan, Jr., later identified two young men depicted in a Dallas police crime scene photograph taken on November 22, 1963, as brothers, but could not recall their names. He said they were older than him, so he did not associate with them, but recognized them from the neighborhood. I told Lad that the young men were indeed brothers – Carl and William Arthur “Bill” Smith – and that both had identified themselves in the photograph years earlier. [68] I asked Lad if he recognized the name Jimmy Markham, but he did not. [69]

Doris Holan’s Dodge

After being shown a series of crime scene and other photographs, Holan stated that his mother’s car appeared in the background of a photograph taken by Dallas Times Herald photographer Darryl Heikes (No.13). The car was parked on Patton Avenue, near a telephone pole located just north of the family apartment at 113 ½ S. Patton Avenue. Holan stated that his mother drove a Chrysler or a Dodge, though he couldn’t recall the specific model or year. [70]

Lad stated that his mother was working “afternoons and nights” at the time of the Tippit shooting. Asked if his mom was home when he arrived at the apartment, Lad said, “I don’t remember. I don’t think she was home. I really don’t.” [71]

Asked if the presence of the automobile meant that, contrary to his recollection, his mother, Doris, was home on November 22, 1963? Lad Holan stated that, “No, because a lot of times she would go with [her boyfriend] “Bill” in his car to the Longhorn Ballroom.” [72]

I pointed out that the Heikes photograph that showed his mother’s car parked on Patton Avenue was taken at about 1:45 p.m. and that another photograph of Patton Avenue, taken by the Dallas Police Department Crime Lab between 4:00 and 4:15 p.m., showed that his mother’s car was no long parked where it had been earlier.

I told Holan that the car had clearly been moved between the two exposures and asked if that would indicate that his mother had in fact moved the car during that interval?

|

Fig.11 - (TOP) Heikes photograph taken at 1:45 p.m. on Nov. 22, 1963, showing Doris Holan's car (yellow circle) parked near her apartment building at 113 S. Patton Avenue; (MIDDLE) Detail of Heikes photograph depicting Holan's 1955 Dodge Royal sedan; (BOTTOM) Dallas police crime scene photograph taken between 4:00 and 4:15 p.m. on Nov. 22, 1963, showing the same area where Holan's car had been previously parked.

Holan stated that his mother and her boyfriend would “trade off cars. If his needed gas, they would drive hers. If hers needed gas, they would drive his.” Lad told me that in later years he realized that the one least inebriated would do the driving – the selection had nothing to do with the amount of gas available. [73] Of course, his response didn’t really address the question which was whether or not the movement of her vehicle indicated her presence that day.

I asked if the presence of his mother’s car parked on Patton Avenue, and not on Tenth, was a clear indicator that the Holan family live on Patton Avenue on November 22, 1963 (as Lad recalled), and not on Tenth Street, as alleged?

Lad answered, “Exactly.” [74]

December, 1963

In the weeks that followed the assassination, Lad, Jr.’s younger sister got into trouble at school. She recalled that a nun at Blessed Sacrament Church school attempted to discipline her with a “wooden rod” for a second time and that she resisted (“I wasn’t going to let her do it again.”). The school told her mother that her daughter was not being allowed back for the second half of the year. The daughter admits she was a handful at the time. [75]

Right after the Christmas holiday (1963) Lad Jr.’s younger sister was sent back to live with her grandmother, “Gussie”, where she remained until she was nine years old (1966). [76]

Times were more than tough for the Holans. In those days, parishioners at the local churches would have food drives to help out the needy families among them, especially around the holidays.

Lad Jr., remembered the generosity of his own church at Christmas time in 1963. “That year, for Christmas, while I was at [Blessed Sacrament] church serving mass [as an altar boy] – I came home and the church had groceries delivered to our house. I will never forget that.” [77]

End of life

When Doris Holan could no longer care for herself, her youngest daughter arranged to have her mother stay at a nursing home, Golden Acres, 2525 Centerville Rd., Dallas, Texas – near Casa View. The home cashed her Social Security check to cover health care and rent. [78]

On June 23, 2000, Doris Holan told her family, at her eightieth birthday party, that she had terminal cancer. She had known about it for six months but hadn’t told her family because, she said, ‘I didn’t know how to do it.’ The family was upset that she waited to tell them.

Doris E. Holan died a month-and-a-half later, on August 7, 2000.

Lad and his youngest sister both told me that their mother was lucid and in full control of her mental faculties right up until the end. [79]

Conspiracy talk

Ten years before Doris Holan’s death, talk began to circulate in the so-called Dallas JFK research community that something happened near the Tippit murder scene that had not been previously known.

On May 1, 1990, during a Kennedy assassination study group meeting conducted by Jim Marrs (author of the 1989 book "Crossfire"), a presentation on the Tippit murder included the revelation that "a verbal and possible physical altercation [occurred] between Tippit and someone unknown at Marsalis and Jefferson just before the shooting." [80]

In a January 2, 1996, memo to file, Southern Methodist University (SMU) professor and JFK assassination researcher William J. “Bill” Pulte wrote: “There are neighborhood reports of a disagreement at the intersection of 12th and Marsalis ‘a few minutes before Tippit was killed.’ Tippit was headed precisely toward 12th and Marsalis when he left Lancaster and 8th. (The report of the 12th and Marsalis argument is from someone whose identity needs to be protected.)” [81] Pulte did not further identify the source of the claim.

Twenty-days later, in a letter to author Harrison E. Livingstone (High Treason), professor Pulte wrote: “There is a neighborhood account that Tippit’s assailant came down the driveway between the two houses” at 404 and 410 E. Tenth Street. Pulte wrote that “this report is plausible because it has been shown that the assailant was not walking east, and the testimony that he was walking west is contradictory. (Of course, the assailant might have been walking west, seen Tippit’s patrol car approaching from a distance, and then ducked up the driveway momentarily.)” [82] Pulte did not state whether the source of this claim was same as the source of the “disagreement” allegation.

Three years later, in a January 18, 1999, letter to Harrison E. Livingstone, the source of one of the claims became clear. Professor Pulte wrote: “Informant H2, who reported a fight at 12th and Marsalis a few moments before the murder of Tippit, also provided the following information: the assailant ran westward down the alley, turned right at Crawford, ducked into the ‘hospital area’ of the Abundant Life annex, hid there for a while and then made his way to [the] second floor of the annex building. By this time, his pursuers had passed. The assailant climbed out of a second-floor window at the SE corner of the building, jumped to the ground (the second floor is quite low), and continued across Crawford and down the alley westward. I told Larry Harris what H2 had said, and he looked amazed. He said, ‘You know, Bill, Penn [Jones] used to talk about the old hospital beds down in the basement of the church annex building.’” [83]

Pulte’s source (identified only as ‘H2’) was a reference to the youngest son of Doris E. Holan, whom Pulte (or another unidentified individual) had obviously spoken to by 1990. [84]

Pulte has never explained how Doris Holan’s youngest son, who would have been ten-years-old at the time, could have witnessed all of the activities attributed to Tippit’s killer – activities that no one else claimed to have witnessed – and yet never revealed any of it to his family or police.

In 1999, Harrison E. Livingstone published an “electronic” book (a password protected website, actually) titled, “Stunning New Evidence in the JFK Case.” In Chapter Six: The Murder of Officer Tippit, Livingstone published much of what he had been made privy to by Bill Pulte in his previous letters.

Five years later, in 2004 (four years after Doris E. Holan’s death), Livingstone published a book titled, “The Radical Right and the Murder of John F. Kennedy: Stunning Evidence in the Assassination of the President,” which repeated much of what had appeared in the 1999 electronic version with some new information tossed in. Chapter Seven: The Murder of Officer Tippit, included the following:

“There are neighborhood reports of a disagreement at the intersection of 12th and Marsalis, ‘a few minutes before Tippit was killed.’ Tippit was headed precisely toward 12th and Marsalis when he left Lancaster and 8th (the report of the 12th and Marsalis argument is from someone whose identity needs to be protected). The late Cecil Smith witnessed this fight which was actually at 10th and Marsalis. One of the individuals was stabbed, but it was never investigated, apparently. It occurred just two blocks east from where Tippit was shortly murdered. One source said the fight started a minute after Tippit was shot. [85]

In this re-telling, the site of the “disagreement” (which is now reported as a stabbing) moves from 12th and Marsalis to Tenth and Marsalis. In addition, a second witness to the stabbing is reported – Cecil Smith, now deceased.

Later in the book, Livingstone published – for the first time – a story attributed to Doris E. Holan. Livingstone wrote:

“Mrs. Doris Holan lived at 409 E. Tenth Street where her windows looked directly upon Tippit’s prowl car and the scene of the murder. Holan is a previously unreported witness to the Tippit murder, and she described what she saw to Dallas researcher Michael Brownlow prior to her death in 2000. Brownlow met with Holan twice, once accompanied by Prof. Bill Pulte. Holan was suffering from terminal cancer, and died a few months later. Her account provides important new information regarding Tippit’s murder. In November, 1963, Holan had a second-floor apartment at 409 E. Tenth. On the 22nd, she had returned home from her job that morning and a few minutes after 1 P.M. Holan heard shots. She went immediately to the window of her apartment facing Tenth. She saw Tippit’s car across the street parked in front of the driveway between 404 and 410 E. Tenth, and Tippit was lying in the street near the left front wheel of the car. She saw a man leaving the scene, moving westward toward Patton. Holan also noticed something else that does not appear to have been reported previously: a second police car in the driveway, which went all the way back to the alley, moving very slowly toward Tippit’s car on 10th. Near the police car she also saw a man in the driveway walking toward the street, where Tippit’s car was parked. She went downstairs at once and over to Tippit. The man in the driveway continued to the street, walked in front of Tippit’s patrol car, paused and looked down at Tippit’s head, and retraced his path up the driveway. At the same time, the police car changed direction and backed up in the driveway to the alley running parallel to Tenth, behind the houses at 404 and 410. In 1963, the driveway could be entered from the alley from the rear, as well as from Tenth. Because Tippit’s car was parked in front of the Tenth St. entrance, the alley provided the only egress from the driveway for the driver of the police car. Holan’s account of a second police car at the scene of the murder is supported by the comments of Sam Guinyard, who told Brownlow in 1970 that he saw a police car in the alley shortly after the police shooting. The man in the driveway was apparently also seen by others: a resident of the neighborhood, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Pulte in 1990 that he had heard about a man in the driveway who approached Tippit’s car. The unidentified police car seen at Oswald’s rooming house at 1026 N. Beckley was there about 1:03 p.m., according to the housekeeper. This car may have been the same one seen by Holan and Guinyard a few minutes later. Tippit died about 1:10 or 1:15 at the latest, allowing time for the car seen by Roberts to go to the driveway between 404 and 410 E. Tenth. Pulte poses questions raised by this information: Why was the second police car in the alley, and who was driving it? Who was the man in the alley? Was the police car seen by Holan the same car seen by Earlene Roberts a few minutes before at Oswald’s rooming house and a few minutes later at the scene of Tippit’s murder?” [86]

The claim was repeated in Joseph McBride’s self-published 2013 book: Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J.D. Tippit (Hightower Press, Berkeley CA., June, 2013) and heralded by John Armstrong on his website “Harvey and Lee” as the key to the conspiracy to murder Officer J.D. Tippit and to frame Lee Harvey Oswald.

In a July 6, 2015, videotaped interview, Michael G. Brownlow and retired SMU professor William J. “Bill” Pulte provided details about the Holan story. Brownlow did most of the talking during the interview. Pulte, sitting beside him, seemed to fall asleep several times. [87]

Brownlow stated that he was the one who initially interviewed Holan and that later Pulte accompanied him to the nursing home where Mrs. Holan was residing. Brownlow claimed that after their visits in person, he and Pulte “talked to her on the phone together a couple of times.” [88]

Brownlow claimed that Holan told them that she worked all night at the Marriott Hotel and returned to her upstairs apartment at 411 E. Tenth Street at about 7:30 a.m. the morning of November 22, 1963. (The address of the upstairs apartment was actually 409 E. Tenth.)

Brownlow said that before she went to bed that morning, Doris Holan called her sister. [89] That, of course, would have been impossible. Doris had only one sister – Laura Elizabeth “Betty Jo” (Middleton) Ray – who was killed in an apartment fire in 1958. [90]

Brownlow stated that Holan told him she awoke at about 1:12 to 1:14 p.m. – “somewhere in that neighborhood” – lit a cigarette and heard four shots.

Brownlow then provided a detailed account of what Holan allegedly told him – details that went far beyond, in my opinion, what one would expect to hear in an interview conducted thirty-seven years after the fact. This is an indication that either Holan or Brownlow or both were exaggerating the account:

“And I asked her, I said, ‘Miss Holan, are you sure it was four shots?’ She said, ‘Big Mike’ – she called me ‘Big Mike’ – she said, ‘Yes,’ she said definitely, ‘It was four shots.’ She said, ‘I was sitting on the bed in my pajamas.’ And she said it startled her and she dropped her cigarette. She reached down and picked the cigarette up and put it in an ashtray. She got up and she ran from the back bedroom – she lived in the upstairs apartment – the bedroom’s in the back – and there was like a middle room and a kitchen – a little kitchen and dining room together, and a little hallway and bathroom and then the living room. So, she ran from the back to the living room and threw the curtain back and looked out the window and she could see this officer – Dallas police officer laying in the street; saw his squad car. And she said, on the sidewalk was a man. She said he had a gun in his hand. He had on a white jacket, black pants – ah – kind of a receding, balding hairline. And as she threw the curtain back, I guess the motion of the curtain – ‘cause he was facing her – he looked up and saw her in the window. And she looked at him. I asked her – I said, ‘Miss Holan,’ I said, ‘when you looked him in the face,’ I said, ‘and he looked at you?’ And she said, ‘Yes.’ She said – I said, ‘Do you think from the distance, where you were looking down and he was looking up, could you have identified him?’ She said, ‘Well, I’ve always said it like this,’ she said, ‘The man that I saw later that evening on TV and in the interviews and when Ruby shot him,’ she said, ‘if it wasn’t him, it was his twin brother.’ She said, ‘But on the day of, if they would have asked me, could I identify him? I would have had to say, no, she said, because I don’t think I could have made a positive identification.’ She said, ‘But, it most definitely, to a ninety-percent probability was that man that I saw on TV later.’ She said, same height and – she noticed that his hair was kind of out of place…” [91]

After looking out the window at Tippit’s assailant, Holan reportedly told Brownlow that at that moment a strange thing happened.

As she watched the man in the white jacket, a second man walked down the driveway in a dark blue jacket. Mrs. Holan claimed the second man was about the same height as the man in the white jacket but much heavier – weighing well over two-hundred pounds.

She also claimed she saw a Dallas police squad car, that apparently originated from the back of the lot, rolling slowly down the driveway toward the street. About half-way down the driveway, the squad car stopped.

“She said, I could see this – on the left side – the cherry – what they called the ‘cherry on top’,” Brownlow tells us. [92]

Mrs. Holan told Brownlow that the heavy-set man in the blue jacket hurried down the driveway and walked out into the middle of street, and looked down at the officer. He had nothing in his hands.

“And then he turned to the man in the white jacket,” Brownlow said, “and began to do this [gesturing with his arm as if to say ‘Go on’] – like telling him to leave; get out of there. She said, that’s when the man in the white jacket turned to his left and proceeded toward Patton.” [93]

Mrs. Holan told Brownlow that she watched the man in the white jacket until he disappeared from view, rounding the corner house and heading south on Patton Avenue. Her eyes shifted back to the heavy-set man in the dark blue jacket, who was now retreating back up the driveway toward the police car, which was continuing to back-up in the driveway. [94]

“So, she ran back to her bedroom and threw on some – she like – what we call women’s sweats, Brownlow said. “She had a pajama bottom on, but she wanted – she said she had some black sweats – sweat pants like – and then she had a top laying on a chair.” [95]

Here again, Brownlow provides an over-abundance of detail that sounds more like exaggeration than truth.

Then, Brownlow said, “And she grabbed her glasses and slipped on some shoes and she ran down the steps and ran out to the street.” (emphasis added) [96]

Lad Holan, Jr., did confirm that his mother wore eye-glasses in 1963, and was near-sighted (i.e., everything beyond a short distance is blurry without the corrective lenses). [97]

This is an important point because it means that everything Doris Holan claimed to have seen, before she put on her glasses, would be highly questionable if not impossible, depending on how strong of a prescription she needed to correct her vision.

Brownlow then told the story of the stabbing incident that reportedly occurred at the corner of Tenth and Marsalis at about the same time that Tippit was shot.

“Miss Holan’s son (identified as “Jimmy Holan”) was coming up the street,” Brownlow said, “and he was on a bicycle and as he – boy, he – fast as he could pump and he got up to the [Tippit] scene; he saw his mother standing out there and he saw the policeman and she told him – Miss Holan said she told her son – he was – he was – I think he was seventeen at the time, or sixteen. He wasn’t as old as Jimmie Burt, but he knew Jimmie Burt then. He knew Helen Markham’s son Jimmy Markham. They all knew each other. And she told her son, she said, ‘Baby, somebody shot this policeman.’ Well, he looked at his mom, he said, ‘Mom, well, I see what’s happening here,’ he said, ‘but, down at the corner,’ he said, ‘a man just got stabbed.’ He said, ‘God, there’s blood everywhere down there.’ He said they threw the man in the back of a blue Mercury or a Lincoln and took off with him.” [98]

I was unable to locate any contemporary newspaper report of a stabbing in the Oak Cliff area as described.

Later in the videotaped interview, Pulte asked Brownlow, “Someone in the neighborhood, who I talked to years ago, told me that he had heard that the person who shot Tippit just briefly ducked up the driveway, but it didn’t help. Tippit stopped anyway and then he came back down to the sidewalk. Did you ever hear that?” [99]

Brownlow replied by saying that one of two men bricking a house located “two houses from the corner of Denver and Tenth” – a man he identified as Eddie Kinsey – looked toward the area of Tippit’s squad just before the shots and said “he saw the man in the white jacket stop and he looked toward one of the houses to his left as if to start up the sidewalk. But, he didn’t, because he started walking back toward him, which confirmed… that the man turned from walking west and started walking back east.” [100]

Pulte said he believed that was what his earlier witness must have been referring to when he heard that the killer ducked up the driveway. [101]

Pulte never identified his “earlier witness”, and Brownlow’s alleged witness doesn’t support the claim. Brownlow identifies his witness as “Eddie Kinsey”, a bricklayer working at a house two doors east of Denver on Tenth.

In fact, there was an apartment complex being bricked at the corner of Tenth and Denver (not a house two doors east). There was a bricklayer present named Francis Kinneth, whom Brownlow no doubt was referring to when he identified him as “Eddie Kinsey”. (The name of one of the ambulance attendants who picked up Tippit was William “Eddie” Kinsley.) However, Kinneth told the FBI in the only known interview conducted in January 1964, that “he had heard approximately two or three shots and, looking in a westerly direction, he saw a parked police car and a uniformed police officer lying on the ground in front of same. At the same time, he observed an individual running west on Tenth and turning south on a street, the name of which he does not know.” [102]

There were three other brick masons on site that day – Elbert Austin, who was assisting Kinneth on scaffolding at the front of the apartment complex; and George Chapman and Perry Holmes, who were both working at the back of the complex. Neither Chapman or Holmes saw the shooting. Austin reported the same thing Kinneth did – he heard two or three shots, looked in a westerly direction, saw a policeman lying in the street, and an individual running west on Tenth and disappearing south on Patton. [103]

None of the bricklayers said that they observed anything prior to hearing the shots, as claimed by Brownlow.

William John “Bill” Pulte

The claims attributed to Doris E. Holan, and her youngest son, originated from retired Southern Methodist University (SMU) Professor William J. “Bill” Pulte and self-proclaimed Dallas researcher Michael G. Brownlow.

Professor Pulte, age 79, has made numerous unsubstantiated allegations about J.D. Tippit over the years in an effort to denigrate and defile his character. In his letters to Harrison E. Livingstone, a dubious researcher and author with a penchant for spreading false rumors and innuendo, Pulte presents a series of unvetted allegations as if they are truth.

In one such letter, dated February, 1999, Pulte expressed his feelings about my book “With Malice” which was published just three months earlier:

“With Malice is a sort of sequel to Case Closed. It seems intended to do for the Tippit murder what Posner tried to do for the Kennedy murder. It is full of holes… But Dale Myers sins even more by omission. His research fails to uncover the most important fact about J.D. Tippit: that he was closely associated with Jack Ruby.” [104]

Here, Pulte inserts eight provably false allegations about Tippit’s alleged connections to Jack Ruby. [105]

“Tippit was no hero,” Pulte concludes, “and the extensive flow of misinformation about his murder, as well as the creation of a phony positive image, leads serious students of the assassination to believe that Tippit’s death must have been very important indeed to merit such attention from political propaganda specialists such as Dale Myers. Harry, you may use my name in citing information which I have sent you (such as items 1-8 [involving Tippit’s alleged connections to Jack Ruby]), but not when I am criticizing Myers. Since I have to live in Dallas, to attack him head-on might be unwise.” [106]

Michael George Brownlow

Michael G. Brownlow, age 65, whose contacts with the Dallas judicial system spans 40-years, is a fixture in Dealey Plaza and a self-proclaimed expert on the JFK assassination offering unsuspecting tourists his insights on the assassination story.

Brownlow’s Dallas County felony and misdemeanor court records - between 1972 (when he was 17) and 2012 (when he was 57) - contain 27 charges (including 19 guilty pleas or convictions) for such offenses as impersonating a police officer, aggravated assault (great bodily harm), robbery (sentenced to 3 years), and unlawful possession of a firearm (multiple counts). All of this is a matter of public record. [107]

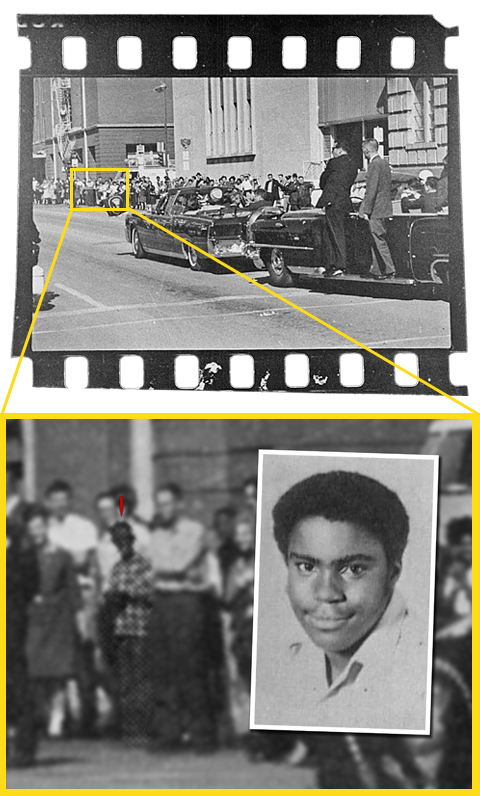

Among his many dubious claims about the JFK assassination, Brownlow alleges that when he was 13-years-old he himself was a witness to the assassination. To support his claim, Brownlow often points to the grainy image of a black youth appearing in the background of a photograph taken by Associated Press (AP) photographer James W. Altgens.

Public records, however, show that Brownlow was born on November 1, 1955, in Potter Co., TX., and therefore would have been 8-years-old (not thirteen) in 1963. Not only is the youth in the Altgens photo clearly older than eight, but the protruding ears of the youth in Altgens are no match for Brownlow’s closely pinned ears.

|

Fig.12 - (TOP) James W. Altgens photograph of the presidential limousine traveling north on Houston Street; (BOTTOM) Detail of Altgens photograph depicting youth identified by Brownlow as himself (red arrow) and a photograph of Brownlow in 1972 at age 17 (insert).

Brownlow also claims to have interviewed more JFK and Tippit shooting witnesses than anyone alive and further claims that he wrote a book on the subject in 1971 called “Shattered Friday,” which, he said, went out of print in 1996.

“I did not re-print the book,” Brownlow told Dealey Plaza tourists. “It cost too much to print it – [corrects himself] re-print it. And I had to pay for the rights to all the witnesses, ladies and gentlemen.” [108]

During a 2015 videotaped interview in Dealey Plaza, Brownlow produced what was purported to be the tattered outside cover of a copy of his 1971 book. On close inspection, the book “cover” is, in fact, the cover of a DVD release of the same title: “Shattered Friday: The Mike Brownlow Interviews” which was originally released on VHS videotape in 2003. [109]

The U.S. Copyright Office has no record of any book written by Michael G. Brownlow, Michael Brownlow, or Mike Brownlow, under any title, at any time in U.S. history.

Brownlow clearly conducted some interviews, as evidenced by the videotape “Shattered Friday,” wherein six on-camera interviews were recorded. [110]

Other interviews and claims made by Brownlow remain unsupported.

Brownlow’s gift for gab has served him well in Dealey Plaza where tourists unfamiliar with the assassination story are easy marks for Brownlow’s narrative tales. But anyone well-versed in the true facts surrounding the assassination can easily see through the showman’s veneer.

Those that challenge Brownlow’s narrative in public have met scorn, ridicule and worse. [111]

Given his lengthy background with the judicial system, volatile behavior, and verbosity when describing interviews that he claims to have conducted – none of which (aside from those presented in his video release) has ever been supported with any kind of documentation – leads many to dismiss his claims rather than embrace them.

Doris Holan’s credibility

The credibility of Pulte and Brownlow’s sources for the Holan story are equally suspect.

Doris Holan’s youngest son (‘H2’ in PULTE’s early letters) was described by other family members as a troubled individual.

His sister, warned me that I couldn’t trust the accuracy of anything he said. “Not that the [stabbing] story’s not true,” she added. I mean, he may have witnessed it, but – [you can’t believe the details].” [112]

Lad Holan, Jr., also stated that while a stabbing was not an unusual occurrence in Oak Cliff in those days and his brother certainly could have witnessed such a thing, he cautioned that his brother was known for exaggeration. “I love him, okay?” Lad, Jr., told me. “But he has a way of dramatizing or making stuff up.” In 2021, Lad added that he found it hard to believe that his brother could have witnessed a stabbing and never told any family members about it, that Lad himself had never heard of a stabbing on the day of the Tippit shooting until I told him about it in 2020, and that his younger brother never owned a bicycle (which Brownlow claimed he rode back to Tenth on after witnessing the stabbing) until they moved to Garland years later. [113]

Asked if his younger brother was a credible source, Lad, Jr., laughed and said, “I wouldn’t [bet] my life on his version [of events].” [114]

Family members were also well-aware that their mother, Doris E. Holan, had a life-long battle with alcohol.

When first contacted and asked about Doris Holan’s claims, one family member wrote, “…I would not believe anything [she] said. I didn’t.” [115]

Those sentiments weren’t isolated. Asked about his mother’s credibility, Lad, Jr., stated, “My mother, bless her heart, always wanted things to be bigger and better than they were. So, if she could dress it up a bit, she would.” [116]

Where did Doris live?

The central question surrounding the Holan story is whether the Holan family actually lived on Tenth Street as claimed by Pulte and Brownlow.

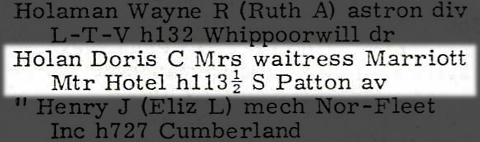

Questions about the Holan family’s residency arose almost immediately when it was discovered that the 1964 Dallas City Directory showed that Doris E. Holan lived at 113 ½ S. Patton Avenue – around the corner from the Tippit shooting scene.

While it was initially thought that the 1964 Dallas City Directory listings were gathered between September and December 1963 (which covered the period of the assassination), and therefore was indicative of the Holan’s living on Patton on November 22, 1963, it was subsequently learned that the listings were gathered between December 1963 and March 19, 1964, and therefore did not reflect where the Holan’s were living on the day of the assassination. [117]

|

Fig.13 - Dallas City Directory listing for Doris E. Holan (the middle initial 'C' is incorrect).

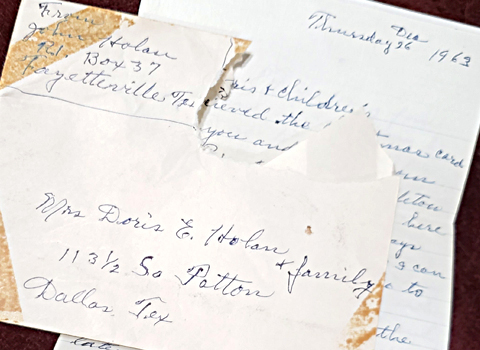

Following my initial questioning of Doris Holan’s youngest daughter about where they lived at the time, she located a letter, dated December 26, 1963, from John Holan to “Mrs. Doris E. Holan & Family” living at “113 ½ S. Patton, Dallas, Tex.” The letter, written by her ex-father-in-law, thanked Doris for the Christmas card she had sent – which obviously had been mailed at least a week earlier. [118]

|

Fig.14 - Letter, dated December 26, 1963, from John Holan to his ex-daughter-in-law, Doris E, Holan and family, 113 1/2 S. Patton Avenue, Dallas, Texas.

After questioning Lad, Jr., about the period in question it became abundantly clear that the Holan family lived at 113 ½ S. Patton on November 22, 1963, having moved there from 409 E. Tenth, where they lived in 1962-63.

When questioned at length about this issue, Lad, Jr., stated that he was “definite” that they lived at 113 S. Patton on November 22, 1963 (“I was definitely living there at the time.”), [119] and while he initially thought that they later moved to the apartment at 409 E. Tenth Street, the contemporary record confirms that the Holans lived on Tenth Street in 1962-63, and then moved to Patton prior to the Tippit shooting. [120]

When asked if it was “possible” that he lived on Tenth on November 22nd and later moved to Patton, Holan insisted that he was living on Patton on the day of the JFK assassination and the shooting of Officer Tippit and that he recalled walking past the house that they had previously lived in (409 E. Tenth Street) on his way home from school every day. [121]

Furthermore, Lad, Jr., stated that his mother, Doris, never talked about the events of November 22nd to her family, and that he had never heard the story that had been attributed to his mother by Pulte and Brownlow regarding a second police car. “No, she never did [talk about that day], and that’s the reason why I don’t think she was there.” [122]

Photographic proof

While the 1963 Christmas letter, and Lad Holan, Jr.’s recollections were all indicative of the family living on Patton Avenue, the evidence that sealed it for me was a photograph taken by Dallas Times Herald photographer Darryl Heikes at about 1:45 p.m. on November 22, 1963, shortly after the Tippit shooting.

In the background of the photograph, Heikes had captured the Holan’s apartment building at 113 S. Patton Avenue. I had sent it to Lad Holan, Jr., in the hopes that it might evoke some additional memories – which it did. More important, he spotted something in the photograph that only he would have recognized – his mother’s car, parked near the front of the apartment building.

Doris Holan drove a 1955 Dodge Royal sedan in 1963 and there it was, parked on the west side of Patton, facing south. Dallas Police Crime Scene Search photographs, taken during the same time period that day, show plenty of parking available on Tenth Street for any resident of 409 E. Tenth. Obviously, if Doris Holan was living at 409 E. Tenth on the day of the Tippit shooting, as claimed by Pulte and Brownlow, she could have parked right in front of her residence and not 300 feet away on Patton.

Given all of the evidence – testimonial, textual and photographic, it is obvious that Doris Holan was not living on Tenth Street on November 22, 1963, and therefore could not have witnessed the Tippit shooting as claimed.

No exit for conspirators

Even if one disregards the question of her residency, the story allegedly told by Doris Holan could not have happened as described.

Pulte and Brownlow claimed that Mrs. Holan told them that a second police car was in the driveway of the house where Tippit stopped and escaped the scene by exiting the driveway via the alley. Yet, Dallas Police Crime Scene Search photographs taken within hours of the shooting clearly show a garage, or other large structure, blocking access to the alley from the driveway.

|

Fig.15 - Detail of a Dallas police crime scene photograph taken on November 22, 1963, showing a garage or other large structure (red arrow) blocking access to the alley from the driveway of the house at 404 E. Tenth.

|

Fig.16 - Detail of a Heikes photograph taken on November 22, 1963, showing the same structure (red arrow) blocking access to the alley.

|

Fig.17 - Detail of a 1964 FBI photograph showing the same structure (red arrow) blocking access to the alley.

Aerial photographs taken by the FBI in March, 1964, also show the same building. Had a second police car been in the driveway, as claimed, it could not have escaped the scene via the alley.

|

Fig.18 - Detail of a 1964 FBI aerial photograph showing a garage or other large structure (red arrow) blocking access to the alley from the driveway of the house at 404 E. Tenth.

I asked Lad Holan, Jr., who as a young teen had discovered which fences he could hop and which yards he could cut through to make navigating the neighborhood easier, whether the photos matched his recollection? “Oh, yeah. Because some of those yards we could cut through and some we couldn’t. And – yeah. That was one you couldn’t. Because there was a fence in the back and the trash trucks went down the alley. Now, there were a lot of [police] cars there shortly after that because, you know, the publicity of a policeman being killed – there were cars everywhere and there could have been one there later in the alley, but not in that driveway.” (emphasis in original) [123]

In the fifty-seven-year history of the Tippit case, only Doris Holan allegedly claimed to have witnessed the vehicle’s presence.

Michael G. Brownlow later said that Sam Guinyard, a porter at Dootch Motors, offered support for Holan’s allegation. Brownlow claimed that Guinyard told him in 1970 that he saw a police car in the alley shortly after the shooting. However, Guinyard never mentioned the vehicle in his Warren Commission testimony nor has Brownlow ever offered any documentation to support his alleged interview with Guinyard.

Lad Holan, Jr., who was an eyewitness to the immediate aftermath of the shooting, arriving at about 1:18 p.m., stated that there was only one police car at the scene when he arrived, which was Tippit’s own patrol car. According to Lad, Jr., the first police car to get to the scene pulled up immediately after the ambulance arrived. [124] Lad Holan’s claim is supported by recorded Dallas police radio transmissions which show that the ambulance dispatched by the Dudley M. Hughes Funeral Home arrived at the scene at 1:19 p.m. My own reconstruction of the police response shows that the first officer to get to the scene – Dallas Police Reserve Sgt. Kenneth H. Croy – arrived approximately 30-seconds later.

Lad Holan, Jr.’s credibility

I found the recollections of the Lad A. Holan, Jr., and other family members to be highly credible. Despite the passage of fifty-seven years, and their ages at the time of the event, their memories were remarkably intact.

Holan was mature beyond his years in 1963. His baptism into adult-life at an early age, and his ability to successfully navigate it, is no doubt the major reason why he was able to faithfully recall many aspects of his young life, where other children of the same age would have failed.

The fact that Holan had spent little time reading about the assassination story prior to my contact with him was a rare bonus, because he was able to offer a fresh, untainted perspective of the day’s events as he remembered them.

Lad Holan stated that I was the first person to ever contact him about his recollections of November 22, 1963. “As a matter of fact, my wife didn’t know some of this stuff,” he said. “She had no idea that I grew up in such a rough part of town.” [125]

He first took his wife to Dallas in 1998, the year before they were married, and showed her where he was standing during the motorcade. She took a photograph of him at the location, which Holan later sent me. [126]

I was able to locate a youngster, that appeared to be Holan in a photograph of the JFK motorcade taken by Charles Bronson as the limousine passed the Dallas Criminal Courts Building at Main and Houston. The Bronson photograph, which he was unaware of prior to my contact, substantiated Holan’s recollection of his attendance and location at the parade. Holan confirmed that the youngster in the photograph was him, although he was unable to identify his father amid the crowd gathered in the shadows nearby.

|

Fig.19 - (TOP) Charles Bronson photograph of the presidential limousine in front of the Dallas Criminal Courts Building on Houston at Main; (BOTTOM) Detail of Bronson photograph showing area where Lad Holan, Jr., (red arrow) and his father were standing as the president's car passed. (Charles Bronson / Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza)

Lad Holan stated that he had read a few things about the assassination but that it was “mainly out of magazines and stuff” and that he had never looked up the subject on the Internet. Asked if he ever read anything about the Tippit shooting in particular, Holan said, “No. No, I didn’t.” [127]

Holan was able to recall details about the Tenth and Patton area of Oak Cliff that are not generally known, including people and businesses that have long since disappeared. In particular, Holan’s recollections about the owners of Dean’s Dairy Way, where Holan worked at the time, was quite impressive and could only have been known by someone who knew them personally. [128]

Lad Holan, Jr., was not prone to exaggeration, easily admitting when he didn’t recall certain details.

His recollections of the Tippit scene were verified by the testimony of other witnesses, and because of the details he was able to recall, I determined that he arrived at the scene at about 1:17 p.m., shortly before T.F. Bowley notified police of the shooting using Tippit’s squad car radio. He left the immediate area about three minutes later, shortly after the arrival of the first responding officer, Reserve Sgt. Kenneth H. Croy.

I spent a considerable amount of time vigorously fact-checking every aspect of Holan’s account, even portions of his story that had no direct bearing on the Tippit story. I found that his recollections passed the scrutiny test with flying colors – a rare occurrence based on my 43-years of interviewing eyewitnesses.

There were a few minor discrepancies between Lad Holan, Jr.’s recollections and the known facts, but none of them were of great consequence. In the end, Lad Holan’s recollections were largely verifiable and given the passage of time, remarkably – though not unreasonably – detailed.

Finally, efforts by some to undermine Lad Holan, Jr.’s story since the initial publication of this research article have been met with corroborating information that supports and confirms the facts presented herein.

All things considered

Doris E. Holan’s account of the Tippit shooting, as alleged by William J. “Bill” Pulte and Michael G. Brownlow, is not credible.

Additional details provided by her youngest son, as alleged by Pulte and Brownlow, are also suspect given the level of detail provided and the source.

Both Mrs. Holan and her youngest son were identified by other family members as having both personal problems and a penchant for exaggeration.

Overwhelming evidence has been uncovered to establish that Doris E. Holan and her family were living at 113 ½ S. Patton Avenue on November 22, 1963, having moved from the apartment at 409 E. Tenth, where she is alleged to have witnessed the Tippit shooting.

Doris Holan’s alleged claim that a Dallas police car was parked in the driveway between 404 and 410 E. Tenth Street at the time of the Tippit shooting and escaped via a back alley is not credible given the presence of a building that would have prevented the vehicle from exiting the property via the alley.

Lad Holan, Jr., did not believe that his mother, Doris, was home at the time of the Tippit shooting, despite a photograph taken 30-minutes after the shooting that shows her automobile parked in front of their apartment building.

Even if she was at home, she could not have seen the Tippit shooting (which occurred around the corner, in front of 404 E. Tenth Street), from any of her 113 ½ S. Patton Avenue apartment windows. However, she could have seen a portion of Lee Harvey Oswald’s escape as he fled south on Patton Avenue, passed her apartment building.

Pulte and Brownlow, both known for spreading misinformation about the Tippit shooting, apparently learned of an alleged stabbing in the Oak Cliff area from Doris Holan’s youngest son in 1995.

Originally, the stabbing incident was reported to have occurred at 12th and Marsalis, and later at 10th and Marsalis. It is unclear from Pulte and Brownlow’s re-telling if Doris Holan’s youngest son witnessed the stabbing, or just its aftermath.

Pulte and Brownlow have since claimed to have located other witnesses to the stabbing – all affiliated with Crown Plumbing Supply – Miss Harriet (last name unidentified), alleged owner of the business; Tom Black, employee of Crown Plumbing; and Cecil Smith (otherwise unidentified).

The founder and president of Crown Plumbing Specialties, Inc., 621 E. Tenth Street, was actually Jack H. Siegel (1921-1982). No one named “Harriet” was associated with the immediate family. [129]

Brownlow identified Doris Holan’s youngest son as “Jimmy Holan”, and said that he was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time. Genealogy records show that Doris had no son named “Jimmy”. The only Holan son who could have witnessed the alleged stabbing, was 10-years-old in 1963.

By their own account, Pulte and Brownlow, did not interview Doris E. Holan until shortly before her death on August 7, 2000.

Originally, Harrison E. Livingstone wrote that “Brownlow met with Holan twice, once accompanied by Prof. Bill Pulte” and that she died “a few months later.” [130]

Later, Brownlow stated that he and Pulte met with her once at the nursing home and spoke to her a couple of times on the phone. [131]

Mrs. Holan did not tell her own family that she had terminal cancer until June 23, 2000, on the occasion of her 80th birthday party.

It seems likely that Pulte and Brownlow’s face-to-face meeting occurred at the nursing home sometime in July when they would have been accompanied by a family member – probably Doris Holan’s youngest son.

Numerous attempts to contact Doris Holan’s youngest son (including a letter and multiple voice messages left on his personal mobile phone, in which I identified myself and the purpose of my call) were met with silence.

My written request for a transcript of the interview or any documentation that would support Doris E. Holan living at 409 E. Tenth Street on November 22, 1963, was also ignored by Professor Pulte. [132]

To date, neither Pulte nor Brownlow have produced anything to support the contents of what Doris Holan reportedly told them.

Not credible on any level

In my mind, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.

Given the extraordinary claim attributed to Doris E. Holan – a claim that is completely at odds with all other known eyewitness accounts – I submit that only extraordinary proof could be offered to support Holan’s residency at 409 E. Tenth on November 22, 1963, and her alleged claim that two Dallas police officers were present when Patrolman J.D. Tippit was murdered.

Given the facts I gathered over the last seven months, and presented herein, it is quite evident that no such proof will ever be forthcoming since the Doris E. Holan story – as presented by Pulte, Brownlow and their surrogates – is not credible on any level. [END]

Footnotes:

[1] Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics, Birth Certificate No. 29934, Doris Emma Middleton

[2] Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics, Birth Certificate No. 7419, Laura Elizabeth Middleton

[3] Texas Marriage Record No.595

[4] “Woman Dies, 6 Escape Dwelling Blaze,” Del Rio News-Herald, Del Rio, Texas, September 2, 1958, p.1

[5] Denton, Texas Record-Chronicle, January 30, 1937, p.2

[6] No marriage record could be located, although Gordon later listed Doris as his “wife” in WWII draft registration documents submitted in approximately October, 1940.

[7] U.S. Census, April 24, 1940, Port Lavaca, Calhoun Co., TX [NOTE: After her marriage to Lad Holan in 1945, Doris’ two sons Curtis and Lee Sides went by the surname: Holan.]

[8] Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics, Birth Certificate No. 41890, Ladislov August Holan

[9] WWII Draft Registrations, 15 Feb 1942, Lad A. Holan

[10] Morrison & Fourmy’s Fort Worth City Directory, 1956, p.459

[11] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 6, 2020, p.35

[12] Interview of Holan family member, June 3, 2020, p.5

[13] Ibid., p.6

[14] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 6, 2020, p.13

[15] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 16, 2020, pp.52-54

[16] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 6, 2020, p.5 [NOTE: The first directory listing showing Doris Holan living in Oak Cliff dates to the fall of 1961, following her divorce: 1819 S. Marsalis. (Polk’s Greater Dallas City Directory, 1962, p.746; Published: June 11, 1962)]

[17] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., March 26, 2021, Pt.2, p.25

[18] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 6, 2020, p.9

[19] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 16, 2020, p.11

[20] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., July 14, 2020, p.5

[21] Ibid., p.6

[22] Email, Lad A. Holan, Jr., to Dale K. Myers, June 25, 2020, p.1

[23] Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate No. 7179, Samuel Edgar House, Sr.

[24] Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate No. 75374, Myrtle Una House

[25] Dallas City Directory Listings, 1964-1996

[26] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., July 14, 2020, pp.6, 9

[27] Books and Pamphlets, Including Serials and Contributions to Periodicals, July-December, 1963, Catalog of Copyright Entries: Third Series, Vol. 17, Part 1, No. 2, p.1396 – Copyright Office – Library of Congress – Washington: 1965 [NOTE: The Cole’s Criss-Cross Cross Reference Directory contains information arranged by address (first by street name, then by house number) or by telephone number. Like the listings for R.L. Polk & Company’s Greater Dallas City Directory, listings for Cole’s Criss-Cross Directory were compiled between late September and mid-December the year prior to publication. The directory was then published and distributed about 7 months later. Consequently, the 1963 Cole’s Criss-Cross Directory listings were gathered in September-December of 1962 and published on July 25, 1963. There were no listings for Doris Holan in either the 1962 (for fall 1961) or the 1964 (for fall 1963) Cole directories, despite the fact that Mrs. Holan – according to her son Lad – kept the same phone number during that period.]

[28] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., March 26, 2021, Pt.2, p.24

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., p.25

[31] Ibid., p.4 [NOTE: According to one family member, the Holan family was living at 113 ½ S. Patton by September, 1963, although the exact date could not be confirmed by other family members.]

[32] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 16, 2020, p.7, 23 [NOTE: Lad, Jr., later recognized Garrett’s pick-up truck parked in front of 113 S. Patton Avenue in a photograph taken by Dallas Time Herald photographer Darryl Heikes on November 22, 1963. (Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 16, 2020, p.18)]

[33] Doris had retrieved her youngest daughter, age 6, from her parents’ home in Terrell, Texas, where she had been living since age two. (Interview of Holan family member, June 3, 2020, p.6) [NOTE: Lad Holan, Jr.’s recollection is that his youngest sister never lived with the family in Oak Cliff in 1963.]

[34] Interview of Holan family member, June 3, 2020, p.2

[35] “Rev. M. McLane Appointed to Catholic Church,” Tyler Courier-Times-Telegraph, June 23, 1957, Sec.2, p.6

[36] The Texas Catholic, June 17, 1961, p.3

[37] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 6, 2020, p.12

[38] Ibid., p.14

[39] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 16, 2020, p.41

[40] “Clergymen Attend Mass Demonstration,” The Texas Catholic, March 28, 1964, p.2

[41] Polk’s Greater Dallas City Directory, 1962, p.746; 1964, p.733; 1966, p.735

[42] Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 6, 2020, p.32

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid., pp.5-7

[45] Ibid., pp.6-7 [NOTE: The only thing Lad could remember about ‘Doc’ was that he was an older man (“my grandfather’s age”) and that he died of a heart attack. (Interview of Lad A. Holan, Jr., June 16, 2020, p.30) Neither surviving Dean daughter could recall the name of the man known as ‘Doc’, although the eldest daughter stated that he was an employee who worked from 2-10 p.m. as an original employee from the time her father bought the store for a period of about five years. “My dad liked him,” she wrote me. “Unfortunately, they were sad to discover that he was stealing from them, taking sacks of groceries and money from the register, so they had to let him go.” (Email, Dean family member to Dale K. Myers, July 13, 2020, 8:34 p.m., p.1)]