Disclaimer: All is Not What it Seems

|

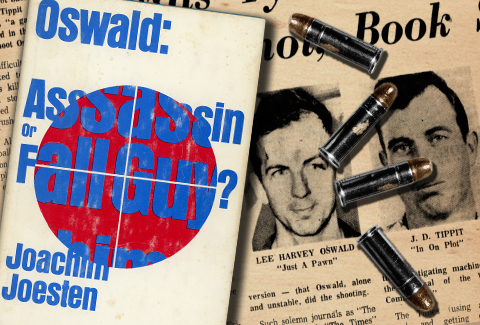

Joachim Joesten's 1964 book and newspaper artcle. [Graphic: Dale K. Myers]

BY DALE K. MYERS

We’re now more than six decades down the road from November 22, 1963, and despite access to more original sources than any previous generation, the path to a clear, concise historical reality seems murkier than ever.

At its core, the solution to the murder of President John F. Kennedy and Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit is simple and self-explanatory. But for reasons that continue to baffle historians, there has been a small and relentless group of historical revisionists fighting to turn the truth on its head and convince an unwitting populace that all is not what it seems. Indeed, all is not what it seems.

Blueprint for revisionists

One of the first revisionists to put his spin on the Kennedy and Tippit murders was Joachim Franz Joesten, a German Marxist who joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in 1932 and fled his native land when Adolph Hitler came to power. Joesten landed in New York City in April, 1941, where he worked for Newsweek magazine as an assistant editor in the foreign department for three-years. By 1944, Joesten was working as a freelance writer. [1]

In early December, 1963, Germany’s biggest publication, the illustrated weekly Der Stern, sent the then 56-year-old Joesten to Dallas, Texas, for the purpose of conducting a thorough private investigation of the many suspicious circumstances surrounding the assassination of President Kennedy.

“On the strength of exhaustive, carefully documented findings, which convinced me that Oswald was innocent and also provided me with valuable clues concerning the identity of the real assassins and their motives,” Joesten later reported, “I wrote a book of around 100,000-words in German (‘Die Verschworung von Dallas’), which is nearly completed (ca. Feb.1964). Excerpts from this book will shortly be published by Der Stern.” [2]

As it turned out, Der Stern magazine apparently found Joesten’s investigative efforts so superficial and his conclusions so speculative that they refused to publish excerpts from the book and instead sought to get their money back. [3] Joesten later claimed that he didn’t know why Der Stern refused to publish his work. [4]

Particularly interesting is Joesten’s reported state-of-mind upon his return from Dallas: agitated, rambling, and somewhat incoherent – comparable to the reaction of many newcomers to the world of the Kennedy assassination.

Mrs. May (née Nilsson) Joesten told the FBI that her husband had been in Dallas for approximately five-days and had returned home telling her that he had information which proved that Oswald did not kill the President. She said that her husband kept rambling on all day about Oswald’s innocence and “also kept it up through the evening and that his statements did not make any sense to her. She stated on one occasion she told him that he should contact the Justice Department but that he did not even seem to hear her. Mrs. Joesten advised that he definitely feels that her husband in on the verge of a nervous breakdown.” [5]

The day after her husband’s return from Dallas, May and Joachim had a dinner appointment which she reminded him of that morning before she went to work. On returning home that evening, she found a note from her husband advising her that he had left for Europe. Mrs. Joesten said that he had never done anything like this before “and that she definitely feels he is suffering from a nervous breakdown and that the statements about the assassination of the President are mere figments of his imagination.” [6]

Upon his return to Europe, and with his Der Stern publication deal in tatters, Joesten approached a French magazine, Le Nouveau Candide, in an effort to recoup some of the finances he spent during his time in Dallas.

In early January, 1964, Le Nouveau Candide published an article by Joesten in which he claimed that after an exhaustive “personal inquiry” which he had conducted in Dallas, he was of the opinion that “Oswald was not the man who killed policeman Tippit” and that it was “very unlikely that Oswald was the assassin of Kennedy.” [7]

Alerted to the French publication, the FBI was interested to find out if Joesten had uncovered any new evidence to substantiate his published allegations, which ran counter to what their own investigation was showing.

On March 21, 1964, Joesten was interviewed by the FBI’s Legal Attaché, at the American Consulate General in Hamburg, Germany, at which time he (Joesten) discussed the depths of his “exhaustive investigation” and the conclusions he had reached. [8]

Joesten told them that he “arrived in Dallas, Texas, on December 6 or 7, 1963, and stayed for four days. He concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald was innocent of the murder of President Kennedy which can be readily seen by a review of published information.” (emphasis added)

Joesten went on to explain that his ‘investigation’ was the result of reviewing newspaper articles published in the Dallas Morning News on November 22-23, 26, 1963; an unidentified New York Times article; and by talking to unidentified citizens on the street.

Joesten said that he knew nothing about shooting or firearms but had personally observed “what would have been the probable angle of fire and had noted that trees would have prevented accurate shooting.” [9]

Fourteen assertions

Joesten’s conclusions were based on the following fourteen assertions:

- Oswald could not have known of the President’s intended motorcade route because it wasn’t published in the Dallas Morning News until the morning of November 22, and therefore Oswald wouldn’t have seen the paper before leaving Irving, Texas, that morning.

- The motorcade route published in the Dallas Morning News showed the motorcade going down Main Street all the way to the Stemmons freeway and not making the turn onto Elm Street past the Texas School Book Depository.

- Governor Connally turned to his left after hearing shots and therefore could not have been shot from behind in his right side below the shoulder blade.

- Parkland doctors said the President was shot in the front of his neck and again in the back of his head. The Governor would have taken a bullet in his heart if he had not turned. This proves conclusively, according to Joesten, that the shots were fired from the front. Published reports about the autopsy are “untrue and part of the ‘cover-up’ in this case.” This is why the autopsy report, according to Joesten, has never been made public.

- Oswald was never legally charged with the murder of President Kennedy, but only charged with shooting Officer Tippit. From this, Joesten concludes, Oswald was “the victim of a deliberate frame-up by the Dallas Police.”

- Witnesses to the Tippit shooting described his killer as “a bushy-haired man about 30…wearing a white cotton jacket…” Oswald was 24-years-old and looked younger. His landlady, Mrs. A.C. Johnson, said Oswald left the rooming house zipping up an olive-brown colored jacket. Photographs published in the Dallas Morning News show Oswald in handcuffs wearing the jacket Mrs. Johnson described.

- According to published reports, Oswald left his rooming house at 1:08 p.m. and Officer Tippit was killed at 1:15 p.m. – too little time for Oswald to get to the scene.

- Newspapers reported that Tippit called a pedestrian over to the car. They spoke briefly. Tippit got out and walked behind the car and approached the pedestrian standing on the sidewalk. They exchanged some more words. Then the man shot the officer. Joesten concludes that Oswald would not have stopped and talked to Tippit if he had just killed the President unless they had known each other previously and the fact that they did talk to each other proves that this was the case.

- The Dallas Morning News reported that “police converged on the area (of the Tippit shooting) and trailed the slayer to the 400 block of East Jefferson. They saw him dart between a service station and a drive-in grocery. (Officers) continued a zig-zag trail westward on Jefferson…” On Sunday, November 24, a few hours after Oswald was killed, Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade told newsmen that witnesses saw Oswald cut across a vacant lot and reload his gun. Joesten concluded that this was “obviously inconsistent because if police saw the killer dart between a service station and a drive-in grocery then the statement of Mr. Wade is untrue that he walked across a vacant lot and was seen to reload his gun. The earlier account is the true one.”

- Despite police claims that Oswald probably had hoped to escape to Cuba via Mexico after shooting Kennedy and Tippit, Officer Tippit was killed on East Jefferson in Oak Cliff – the exact opposite direction from that which would be taken to leave Oak Cliff. “There were no exits from Oak Cliff on East Jefferson. Oswald had no reason to be on East Jefferson where Officer Tippit was killed and was not there.”

- When Oswald left his Oak Cliff rooming house, he was on the run because he feared the police and had become more fearful of the police after his encounter with a police officer in the Texas School Book Depository. At the time Officer Tippit was killed, Oswald was on West Jefferson on his way to see his mother in Fort Worth. Hearing police cars converging on the Tippit scene, Oswald “naturally panicked and took refuge in the Texas Theater not because he had killed the President or Officer Tippit but because of fears of the police for other reasons.” Joesten doesn’t explain these ‘reasons.’

- The New York Times published an article in which Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade said the Tippit shooting scene was only two blocks from Oswald’s rented room. The distance is actually ten blocks. Wade lied because Oswald could not have covered the ten-block distance in the time available to him.

- Mrs. A.C. Johnson, Oswald’s landlady told Joesten that the housekeeper, Earlene Roberts, had seen Oswald leave the house and had seen him at a bus stop leading to downtown Dallas. Joesten claimed that Oswald was pondering going back to Irving to see his wife before going to Fort Worth to his mother. According to Joesten, the fact that Oswald was fearful of the police and was going to see his mother “makes it very logical for him to have been on West Jefferson but he was never on East Jefferson.”

- The New York Times quoted Officer Nick McDonald as saying he “…rammed his hand into the top of the man’s trousers and grabbed the revolver.” According to unidentified newspaper reports, FBI firearms experts found the firing pin of the gun reportedly taken from Oswald so bent that it could not strike the “cap of the bullet.” Joesten concludes, “It, therefore, appears more probable that the pursuing officers who began the search after Tippit was killed actually found the killer and killed him or otherwise disposed of him, took his gun and forced it into Oswald’s hand after they found him, after bending the firing pin on the pistol. This was done to ensure that Oswald could not shoot someone after the gun was forced into his hand.” [10]

From these fourteen assertions, Joesten concluded: “This, therefore, clearly shows (1) Oswald is innocent, (2) the actions of the police and statements of Mr. Wade show no innocent error, therefore, (3) there has to have been a conspiracy to assassinate the President, and make Oswald the ‘fall guy,’ involving the Dallas police.” [11]

The big conspiracy

Joesten told the FBI’s Legal Attaché that the grand conspiracy was hatched by Haroldson L. Hunt and J. Paul Getty, whom President Kennedy had vowed to intimates to crack-down upon. Hunt was the chief financier of the John Birch Society whose membership included General Edwin A. Walker. Joesten stated that the attorney for Oswald’s mother (Mark Lane) had “proof of a mysterious meeting at [Jack] Ruby’s apartment shortly before the assassination of the President and that [Bernard] Weisman and Officer Tippit were present.” Joesten further asserted that Weissman was the individual who had placed a black-bordered advertisement in a Dallas newspaper ‘welcoming’ Mr. Kennedy to Dallas, and that Weissman had told the New York Times that he had been a military policeman in Germany at a time when General Walker was recruiting troops for the John Birch Society and therefore, Joesten added, “they undoubtedly knew each other.” [12]

Joesten said that the cross-fire pattern of the JFK assassination was a “military-type operation” and “since General Walker is an experienced military man it is apparent that he organized the actual execution of the assassination plot.” It is also probable, according to Joesten, that Weissman, also being a military man, had something to do with the assassination. [13]

Once the conspirators decided to assassinate President Kennedy, they enlisted the aid of Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade, Dallas Police Chief Jesse E. Curry, and Dallas County Sheriff Bill Decker because their jobs were dependent upon the good will of Hunt, Getty and other ‘Texas oilmen.’ According to Joesten, this complicity explains the change in the route of the motorcade. Furthermore, according to the Dallas Times Herald, Sheriff Decker came on the police radio at around 12:25 p.m. and ordered all available men to the Elm Street underpass. However, according to Joesten, the president’s motorcade was five-minutes behind schedule. He should have been at the underpass at around 12:25 p.m., but did not arrive there until 12:30 p.m. Joesten reasons, “From this it is obvious that Sheriff Decker was in on the conspiracy but from his office did not realize when he ordered his men to the area, supposedly to apprehend the killer, that the President had not yet arrived at the underpass and had not yet been shot.” [14]

While some shots were fired from in front of the motorcade, Joesten acknowledged that “there was a man shooting from the window from the book depository but it was not Oswald.” [15] In his 1968 book, “How Kennedy was Killed: The full appalling story,” Joesten claimed that the man shooting from the depository was Officer J.D. Tippit. [16]

According to Joesten, when Oswald encountered police in the second-floor lunchroom immediately after the assassination, he fled the building fearful for his life.

The fact that Oswald boarded a bus that was coming back toward the book depository was further proof, according to Joesten, that Oswald was not the assassin since he “would never have done this if he had been the assassin.”

Why was Oswald afraid? Joesten explained that Oswald’s reported defection to Russia was ‘a cover-up.’ “It should be obvious to any casual reader,” Joesten told the consulate, “that Oswald was sent to Russia by the CIA and that he bungled the job he was sent to do.” Joesten offered nothing to back-up his assertion, saying that “he had no personal knowledge of this and no inside information but that it was easily evident to any thinking person.”

According to Joesten, after returning to the United States, Oswald was penniless and was recruited by the FBI as an agent provocateur. Joesten claimed this was “easily seen” by the fact that he ran the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC) in New Orleans against the advice of their headquarters office in New York. According to Joesten, the FBI and CIA had decided to give Oswald a second chance to make up for his failures in Russia.

The speed and ease with which Oswald was issued a passport in June, 1963, to go to Mexico shows “obviously that it was done at the request of the CIA,” according to Joesten.

When Oswald returned from Mexico without having obtained a visa to travel to Cuba, troubled developed between Oswald and the FBI and CIA. Joesten guessed that the “trouble” was probably due to his failure to get the visa, the misappropriation of funds given him, or for some other unknown reason.

Consequently, according to Joesten, Oswald returned to Dallas, Texas, and went underground – fearing the FBI, the CIA and all the American police agencies. Proof of Oswald’s underground status, according to Joesten, was the fact that he registered under the name ‘O.H. Lee’ at the Oak Cliff boarding house. Proof of Oswald’s fear for his life was the fact that he fled after the Kennedy assassination. [17]

The FBI’s Legal Attaché at the American General Consulate in Hamburg, Germany, described Joesten’s visit as “a completely normal appearance, however, he became agitated when any of his ‘facts’ were questioned. He based his conclusions on earlier newspaper reports but dismissed as a ‘cover-up’ any subsequently reported information which tended to show the original reports were inaccurate as they often are in the confused aftermath of a major event.” [18]

No matter

On June 14, 1964, Joachim Joesten’s book, “Oswald: Assassin or Fall Guy?” – largely based on his four-day Dallas investigation and the 100,000-words he had originally written for Der Stern – was published by Marzani & Munsell Publishers, Inc., in the United States. [19]

It was the beginning of a flood of books and magazine articles that sought to challenge the official account of what happened – in the case of these earliest books, months before the Warren Commission had even completed their investigation.

At the end of his January, 1964, French article, Joesten had written, “America waits for someone to get to the truth on the assassination of Kennedy, but at the same time, it fears this truth.” [20]

Won’t someone help get to the truth? That kind of call-to-action is hard to resist when you’re young and naïve. And so, many young people in America began their search for the truth about the Kennedy and Tippit murders, chasing the brushfire that Joesten’s book had lit.

Foul mouths

Millions of words have been written over the last sixty-one years about those four days in Dallas.

Joesten’s book is particularly significant because of its influence on many who followed in his footsteps.

Anyone familiar with the assassination story knows that Joesten’s book is filled with inaccuracies, unsubstantiated allegations and biases. Joesten makes extensive use of speculation, relying on early press reports, many of them confusing and contradictory. In short, if you really wanted to know what happened on November 22, Joesten was the last person you would turn to.

Unfortunately, much of what Joesten alleges has been repeated endlessly by a gaggle of conspiracy advocates over the decades, most of his rubbish finding new life on the Internet where nothing dies and old-information is ‘discovered’ by new generations of enthusiasts eager to find a place for themselves in the world of assassination-ology.

One such Joesten claim – that Jack Ruby employee Curtis LaVerne “Larry” Crafard served as an Oswald look-a-like in the plot to frame Oswald [21] – has recently found new life online. The latest version of this nearly sixty-year-old-claim has Crafard killing Tippit, tossing the revolver he used in the killing onto the street in a paper bag, near Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club, where it was readily found and turned over to police. Such nonsense is considered ‘ground-breaking’ in the world of today’s online conspiracy crowd.

Even Joesten’s reaction to being challenged on his ‘facts’ at the American General Consulate in Germany in 1964 is reminiscent of the reactions of many of today’s conspiracy advocates who have yet to figure out what is sensible and what is not.

Reality check

The Dallas cops had barely caught their breath when they stormed into the Texas Theater in Oak Cliff a little less than ninety-minutes after the President’s assassination. The ticket-taker had telephoned that someone suspicious had just entered the theater without paying. Normally, the police wouldn’t be so worried about a gate-crasher, but the theater was just six blocks from the scene of the brutal daylight murder of one of their own – Officer J.D. Tippit.

Gunned down in front of multiple witnesses, the 39-year-old father of three never had a chance. His killer pumped four shots into his body before he could clear his holster. Now he lay lifeless on a gurney in the emergency room at Methodist Hospital.

The Texas Theater, built in 1932, was within walking distance of the murder scene. It was possible the suspicious man darting into the theater without paying might be the person they were looking for.

With no more information than that, police converged on the theater in force. A shoe store manager, who watched the suspect slip into the theater behind the ticket-taker’s back, and raised the alarm, pointed out the suspect sitting in the rear of the theater.

Patrolman M.N. “Nick” McDonald got to him first. “Get on your feet,” the patrolman commanded. The suspect rose, raised his hands shoulder-high and muttered, “This is it. It’s all over now.”

Believing he was surrendering, Patrolman McDonald reached for his waist to pat him down.

Suddenly, the young man took a swing, and punched McDonald in the face. The patrolman fell back into the seats.

“My God, he’s not surrendering!” McDonald thought.

In a wink, McDonald saw the man’s hand grab for a revolver in his belt-line. He thought he was about to be killed. McDonald lunged forward and grabbed the cylinder of the man’s revolver to keep it from turning.

“I’ve got him!” McDonald hollered.

But he didn’t have him. Not yet. Someone yelled, “Look out, he’s got a gun!”

Several nearby policemen rushed to McDonald’s aid as he struggled for control of the firearm.

McDonald finally wrestled the gun away as the man was handcuffed and pushed out the front doors of the theater toward a waiting police car.

When arresting officers got the suspect to police headquarters downtown, the significance of their prisoner quickly came into sharp focus.

The suspected cop-killer was Lee Harvey Oswald, a 24-year-old employee of the Texas School Book Depository who had left the building within minutes of the presidential assassination.

The rifle he had purchased in March, 1963, had been found on the sixth-floor. Three shells fired in that rifle were also found under an open window where witnesses saw a man shooting at the president. The shells were later proven to have been fired in Oswald’s rifle, to the exclusion of all other weapons, as were bullet fragments found in the presidential limousine. No doubt about it, Oswald’s rifle was the assassination weapon.

Oswald had fled the book depository, jumped on a bus, then switched to a taxi cab, and returned to his rented room, arming himself with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver which he also had purchased in March, 1963. He left the rooming house within minutes, zipping up a light-gray jacket.

Fifteen minutes later, Oswald murdered Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit on a residential side street nine-tenths of a mile from his rented room. Tippit had stopped Oswald, who was walking down Tenth Street. When Tippit got out of his squad car and approached Oswald, he pulled the .38-caliber Smith and Wesson revolver he had just gotten from his room and shot Tippit four times. Eleven witnesses identified Oswald as the person who shot the Dallas patrolman and/or who was seen fleeing the immediate vicinity.

Four spent shells recovered at the Tippit murder scene were later proven to have been fired from Oswald’s revolver, the same firearm ripped from his hand after he pulled it on officers moving in to arrest him in the Texas Theater.

The light-gray zipper jacket that Oswald was seen zipping up as he left his rented room was found on a parking lot two blocks from the Tippit murder scene. Witnesses had seen Tippit’s killer escaping along that path. Fibers matching the color and microscopic characteristics of the shirt Oswald was wearing when he was arrested were found in the sleeves of the discarded jacket. The fiber evidence was further evidence that Oswald was Tippit’s killer.

According to Marina Oswald, her husband owned only two jackets – the light-gray jacket found in the parking lot two blocks from the Tippit murder scene and a dark blue jacket which was discovered in a first-floor lunchroom at the Texas School Book Depository two weeks after the assassination.

Twenty-three minutes after the Tippit murder, shoe store manager Johnny C. Brewer spotted Oswald acting suspiciously in front of his shoe store, located seven blocks west of the Tippit shooting scene. Oswald was in shirt-sleeves; no longer wearing the light-gray jacket his housekeeper saw him zipping up as he left his rented room. Brewer followed Oswald up the street and saw him duck into the Texas Theater behind the ticket-taker’s back. Brewer approached the ticket-taker, Julia Postal, and together they called police.

Evidence of guilt in the assassination

The Dallas police later discovered that before leaving Ruth Paine’s house in Irving on the morning of the assassination, Oswald had left behind his wedding ring and $170 ($1,753.69 today) in cash. Oswald kept a little over $13.87 dollars ($143.08 today) for himself.

As Oswald approached Buell Frazier’s house for the ride back into Dallas, Frazier’s sister, Linnie Mae Randle, saw Oswald carrying a long package.

Before climbing into Buell Frazier’s car, Oswald placed the long package on the back seat. Frazier later said Oswald told him it was curtain rods.

When Frazier and Oswald arrived at the Texas School Book Depository parking lot, Oswald grabbed the long package from the back seat and carried it to the depository, staying fifty-feet ahead of Frazier. Usually, they walked the three hundred yards together.

During his interrogation on Friday night, Nov. 22, Oswald said he was having lunch on the first floor of the book depository at the time of the assassination; however, on Sunday morning, Nov. 24, Oswald changed his story, saying that at lunchtime, one of the ‘Negro’ employees invited him to eat lunch with him but he declined, saying, “You go down and send the elevator back up and I will join you in a few minutes.” Oswald said that before he could finish whatever he was doing, the commotion surrounding the assassination took place and he “went downstairs,” where a policeman questioned him as to his identification. His boss stated he was one of his employees.

Oswald’s statement about being questioned by a policeman shortly after the assassination was a reference to his encounter with Dallas Patrolman M.L. Baker and depository manager Roy S. Truly, who crossed paths with Oswald approximately 90-seconds after the shots in a second-floor lunchroom.

Oswald didn’t specify which upper-floor he was on immediately before the assassination. However, a black depository employee, Charles D. Givens, testified that he returned to the sixth-floor a few minutes before noon to retrieve a pack of cigarettes and encountered Oswald. Givens asked Oswald, “Boy, are you going downstairs? It’s near lunchtime.” Oswald replied, “No, sir. When you get downstairs, close the gate to the elevator,” which would allow Oswald to call the elevator back up remotely.

Two weeks after the assassination, the clipboard Oswald had been using on Nov. 22 was found on the sixth-floor behind some cartons near the northwest corner stairwell, near where the rifle was discovered. Three orders for books, which were located on the sixth-floor, were still attached to the clipboard.

Consciousness of guilt

Oswald lied repeatedly during his interrogation. Here are just a few examples:

- Oswald denied purchasing or even owning the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle found on the sixth-floor. (Documents in Oswald’s own handwriting prove he ordered the rifle and had it mailed to a Dallas post-office box he had rented.)

- Oswald denied that the backyard photograph of him holding the rifle was in fact him. He claimed it was his face superimposed on another person’s body. (Scientific examination later proved that the photographs were genuine and unaltered.)

- Oswald claimed he had never seen the rifle photograph before. (A copy of one of the photographs was later found among the effects of Oswald’s friend George DeMohrenschildt, with Oswald’s signature on the back.)

- Asked by police to reveal all of the addresses he lived at in the past, Oswald provided all of the addresses, except his residence on Neely Street (where the backyard photographs were taken).

- Oswald denied telling Buell Wesley Frazier that he went to Irving the night of Nov. 21 to get curtain rods, denied putting a long package in the back of Frazier’s car, and denied carrying a long package into the Depository. (No curtain rods were found in the Depository.)

- Oswald claimed that the only bag he brought to work on Friday, Nov. 22 was a bag with his lunch in it. (Frazier stated that he noticed that Nov. 22 was the only day that Oswald didn’t bring his lunch and that he thought Oswald planned to buy lunch from the catering truck.)

- Oswald claimed he was having lunch with James “Junior” Jarman at the time the president was shot. (Jarman testified that he ate alone.)

- Oswald claimed that he bought the revolver he owned in Fort Worth. (Oswald actually bought the revolver from a Los Angeles mail-order house around the same time he purchased his rifle.)

- Finally, Oswald denied having any knowledge of the name ‘A. Hidell,’ the name used to order the weapons used to murder President Kennedy and Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit, despite the fact that when he was arrested, his wallet contained a false selective service identification card in the name of ‘Alek James Hidell’ which featured Oswald’s photograph. U.S. Postal records showed that Oswald had authorized ‘A.J. Hidell’ to receive mail in his post office box in New Orleans; filling in the ‘Hidell’ name in his own handwriting. When confronted with the form on Sunday, Nov. 24, Oswald denied any knowledge of the contents of the form or any explanation of why he would put the name ‘A.J. Hidell’, which he claimed to have no knowledge about, on the post-office form.

Oswald’s actions on November 22 and the lies he told police while in custody betray a “consciousness of guilt” – a type of circumstantial evidence that is used in courtrooms to convince juries of a subject’s guilt. The argument is that the actions and statements of the accused are not how one would expect an innocent person to behave.

Oswald’s defenders insist that no one could be that stupid. There must have been more to it, they figure. However, to counter such circumstantial evidence – and the large amount of powerful, supporting, physical evidence – advocates of Oswald’s innocence are burdened with constructing a believable, counter narrative that proves with equally powerful physical evidence that all is not as it seems.

Joachim Joesten, who died in 1975, and those who have followed in his footsteps, have failed miserably in meeting that burden. After more than six-decades, the nitpickers and soothsayers populating today’s Internet forums have built nothing that remotely resembles a believable case for Oswald’s innocence.

Disclaimer

In the recent Netflix limited-series, “Disclaimer,” Cate Blanchett plays a woman whose secret past catches up with her. The assumptions of those around her drive the narrative. The audience is cleverly manipulated into seeing those assumptions as truth. But, as her family, and we the audience, inevitably learn, all is not what it seems.

Particularly powerful is the moment when the destruction of many personal relationships caused by those assumptions is laid bare, and saying you’re ‘sorry’ is just not enough to balance the scale.

It reminded me of the aspersions that have been cast upon Officer J.D. Tippit and the Tippit family. Their beloved husband, father, brother, and uncle has been charged with being a racist, a white supremacist, a dirty-cop, a womanizer, and – perhaps, most heinous of all – a conspirator.

None of those charges have any basis in fact and those making the accusations couldn’t possibly have anything believable to support them. For many conspiracy advocates, it’s all a parlor game, with zero regard for those who get hurt in the process.

And why? What was J.D. Tippit’s crime?

Apparently, being a dedicated police officer and being murdered in the line-of-duty is not reason enough for conspiracy advocates to think before pointing an accusing finger.

Perhaps what they’re really so peeved about, and why they generally avoid truthful discussions about the Tippit killing, is that Oswald’s foolish impulse to murder Tippit revealed his need to escape at all costs, and forever doomed any chance for reasonable people to embrace his claim of innocence in the Kennedy assassination.

Killing Tippit changed everything. Oswald was no longer a political assassin, promoting his twisted Marxist ideology. He was a punk.

Permanent scars

Today, there are fewer and fewer living persons who knew J.D. Tippit. I met many of J.D.’s family and friends in the course of authoring the 50th anniversary edition of “With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit.” Many of them have since passed on.

I learned first-hand of the tremendous hurt they experienced over the better part of fifty-years due to thoughtless and unprovable allegations from the likes of Joachim Joesten and his ilk. The wounds were deep and left permanent scars.

Is it any wonder that the Tippit family ended all outside contact with anyone showing an interest in their dear, departed? Even then, their silence was once again assumed to be a further cover-up of the truth. Good Lord, will anyone who advocates for conspiracy ever admit they were wrong and accept responsibility for their thoughtless and hurtful allegations? Or will continued denial be their chosen course?

Today, I’m among those being assailed for daring to defend the devotion-to-family and dedication-to-duty espoused in the life of J.D. Tippit with the only book, sanctioned by the Tippit family, [22] that lays out the true facts surrounding his life and death.

It’s an excellent, well-researched book, conspiracy advocates say, it’s just that the author came to the wrong conclusions. Really? So, I guess this author was sharp enough to assemble the facts and present them, but too ignorant to be able to assess them intelligently. How stupid is that?

They’ll never get it

Sixty-one years ago today, a dedicated police officer was cut down in the prime of his life by a misguided, Marxist indoctrinated young man who thought so little of his own life, and those around him, that he was willing to murder in order to show that he was someone to be reckoned with. How sad.

The ‘Joachim Joestens’ of the world still insist that all is not what it seems.

I agree. All is not what it seems. But the solution to the Kennedy and Tippit murders is as simple as it gets: Self-hate and loathing destroys lives.

A disclaimer worth pondering. [END]

Footnotes

[1] HSCA – Segregated CIA Collection, September 26, 1968, Subject: Joesten, Joachim Franz; aka Walter Kell; aka Paul Delathius / Note: In November 1943, Joesten was considered for OSS employment but was disapproved because an investigation failed to establish his basic loyalty to the United States and its form of government. Reports were received that Joesten was a German Communist but these were not substantiated. In April 1961 the FBI advised they had no objection to the CIA contacting Joesten for routine interrogation as a source of foreign intelligence information. However, it was learned that he’d departed the U.S. for a year’s tour of Europe and contact interest was cancelled.

[2] Joesten, Joachim, Memo to the Publisher concerning the book ‘Impossible Assassin’, CD1107, Vol.1, p.575

[3] FBI Airtel, FBI Director to SAC Dallas, March 31, 1964, p.2, note; 62-109060 JFK HQ File, Section 55

[4] CD1107, Vol.1, p.588

[5] Ibid., p.578

[6] Ibid.

[7] Joesten, Joachim, “Why I Say: Oswald Did Not Kill Kennedy,” Le Nouveau Candide, No.141, January 9 – January 16, 1964; CD1107, Vol.1, pp.562-563

[8] FBI Report of Assistant Legat John C.F. Morris, March 23, 1964, p.1; FBI 62-109060, JFK HQ File, Section 55; FBI Memorandum, W.A. Branigan to W.C. Sullivan, July 9, 1964, p.1; FBI 105-82555 Oswald HQ File, Section 190

[9] CD1107, Vol.1, p.580

[10] CD1107, Vol.1, pp.579-584

[11] Ibid., p.584

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p.585

[14] Ibid., p.587 Note: Joesten was obviously unaware that Decker was not in his office overlooking Dealey Plaza, at the time of the shooting, but was riding in the lead car of the motorcade with Dallas Police Chief Curry.

[15] Ibid., p.585

[16] Joesten, Joachim, “How Kennedy was Killed: The full appalling story,” Chapter 12: Was Tippit the Man in the Window?, Peter Dawnay, Ltd., Tandem Books, Holland, March 1968, pp.131-143; Letter, FBI Director to Joe B. Tonahill, March 2, 1967, attachments, FBI 62-109060 JFK HQ File, Section 113

[17] CD1107, Vol.1, pp.585-588

[18] FBI Airtel, Legat, Bonn to FB Director, March 23, 1964, p.3; 62-109060 JFK HQ File, Section 55

[19] Joesten, Joachim, “Oswald: Assassin or Fall Guy?” Marzani & Munsell Publishers, Inc., 1964, pp.1-158

[20] CD1107, Vol.1, p.572

[21] DOJ Memo, FBI Director to CIA Director, August 24, 1966, pp.1-2, NARA 1994.04.11.11:59:11:910005; also, FBI 62-109060, JFK HQ File, Section 101; V. Berezhkov, “More Light on the Kennedy Assassination,” New Times, Book Reviews, October 26, 1966, NARA 1993.08.20.11:01:18:530064

[22] Note: I was approached by one of Tippit’s nieces following the publication of the 1998 edition of With Malice. She told me that the family was grateful that finally someone had written a true account of her uncle’s death. Her outreach led to a 25-year relationship with the extended Tippit family that continues to this day.