and the Futile Search for Signal in Noise

|

Josiah Thompson and his latest book. (Graphic: © 2021 Dale K. Myers. All Rights Reserved)

By NICHOLAS R. NALLI, Ph.D.

Last Second in Dallas

Josiah Thompson

University Press of Kansas. 504 pp., $29.95

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Click HERE to download a (1.08 MB) ZIP file containing a PDF version of this article, plus the animated GIFs.]

Introduction

It has been more than 57 years since the shocking and tragic assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, on 22 November 1963. Like the 7 December 1941 Pearl Harbor surprise attack before it, and the 11 September 2001 terrorist attack following, the course of history was changed in an instant. The Kennedy assassination occurred at the height of the Cold War, just over a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, with tensions in Vietnam escalating, and America embroiled in the Civil Rights Movement.

It was within this geopolitical context that President Kennedy made a mundane visit to Texas to maintain electoral support in battleground southern states in advance of the 1964 election. The reception he received during his motorcade in Dallas, riding in an open-top convertible, was warm and enthusiastic… until the last minutes of the downtown route, when gunshots rang out in Dealey Plaza. The news media and American public would soon learn that the suspect arrested in connection with the shooting, a resident in right-leaning Dallas, Texas, was in fact a communist sympathizer, a former U.S. Marine who tried to defect to the Soviet Union. This set of seeming contradictions would be the source of cognitive dissonance for people seeking meaning in the tragedy. While the Warren Commission (WC) would establish that this lone individual murdered JFK, they never established any definitive underlying motive. This, among other things, set the stage for the early first and second waves of “WC critics,” “assassination researchers,” “buffs,” and yes, “conspiracy theorists.” Speculation abounded as to “who killed JFK,” much of it the outcome of the geopolitical context—it was the Mafia, the right-wing segregationists, the Cubans, the Russians, the US military-industrial complex and deep state, ad nauseam... anybody but that “silly little communist”. [1]

Now, while broad public interest in the assassination has gradually waned since the 1990s, there is no shortage of new authors on the topic. Interest in the event continues to wax annually around the anniversary, and the Dallas Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza remains a popular attraction.

It has thus been with some anticipation that a new book by Josiah “Tink” Thompson, a respected first-wave author, was welcomed by the assassination research community. The book’s title, Last Second in Dallas, suggests a follow-up of his 1967 classic, Six Seconds in Dallas, and indeed, it is part sequel, part autobiography. In Last Second, Thompson takes us on his transition from being a young, idealistic, left-wing college professor of philosophy at Haverford College in 1964 to a private investigator, told through the lens of his pursuit of the Kennedy assassination case. Thompson’s fascination with the Kennedy assassination was driven by his serendipitous association with LIFE Magazine and other early researchers who questioned the Warren Commission’s conclusions. However, he was ahead of the curve on the subject, and justly deserves recognition for his early contributions (beyond the mandate-limited Warren Commission Report). Thompson is unquestionably among the more reasonable of the “WC critics,” but he also has the rare talent of being a persuasive public speaker. He contends that he remains focused on investigation of the crime scene (Dealey Plaza), and not any “conspiracy theory.”

As this paper will show, despite what might be high expectations, Last Second in Dallas (LSID) is ultimately a disappointment. Of course, this is not speaking for entrenched “conspiracy theorists” (or “CTs” for short). Although CTs have wide-ranging scenarios, often in stark disagreement with Thompson, many will nevertheless welcome this encore performance from one of the genre's icons, if for no other reason than keeping the JFK conspiracy debate alive. I write this knowing full well that any criticism will be a priori rejected by some CTs, and I also know firsthand of the ad hominem attacks that can be incurred by critics of the “WC critics.” While Thompson himself is generally somewhat more civil and diplomatic than some of the more militant conspiracy-minded ideologues, throughout the book he airs a lingering personal grudge against the late Nobel Prize winning physicist, Prof. Luis Alvarez, a prominent American scientist who earnestly sought to debunk the CTs of his time.

In the Foreword we are advised by Richard Rhodes that “you will find no conspiracy theories here,” presumably because there is no specific hypothesis on who the perps were. But this denial notwithstanding, the book falls solidly within the CT genre because a conspiracy is implied, with three unknown shooters conjectured in Dealey Plaza (i.e., adhering to “triangulation of crossfire” and “Grassy Knoll gunman” scenarios). However, outside of the autobiographical content, Thompson’s implicit goal is not so much as to build a tenable counter-scenario (explaining the who, why and how), but rather deconstruct the well-established “official” scenario. But it is Thompson’s collateral attempt to deconstruct his own legitimate groundbreaking contributions to the case in his original book (which were heretofore generally respected) that I find particularly disappointing about this new book.

LSID does not attempt to provide significant new research of his own not included in Six Seconds in Dallas, but instead attempts to invalidate one of the key conclusions (discussed in detail below). This is presumably because this earlier finding, under closer examination, has since inadvertently pointed to an opposite conclusion. This is something not too uncommon in science, and it can often lead to big breakthroughs, but only if the investigator is objective and detached enough to accept the unexpected conclusion at face value. Otherwise, it will eventually fall on others to do so... because facts are stubborn things.

The book is divided into four chronological parts spanning the author’s career investigating the case: Part I, “Beginnings—The 1960s”; Part II, “Aftermath—The 1970s”; Part III, “Breaking the Impasse—The 2000s”; and Part IV, “The Signal in the Noise—2013-2017.” Parts I and II are more autobiographical and retrospective in nature, whereas Parts III and IV focus on the author’s renewed interest in the early 2000s along with a subsequent new interpretation of his previous work.

Part I: Beginnings—The 1960s

The first part consists of nine chapters where Thompson discusses his early sleuthing on the case during the turbulent 1960s, walking the reader through his journey up through the publication of his first book. These chapters are more biographical in nature and thus make for easy reading, basically telling us the story behind his original bestseller that would gain national attention. Thompson’s narrative in pursuit of conspiratorial mysteries will connect with passionate students of the Kennedy assassination. Readers interested in the case will feel the excitement he must have felt, while working for LIFE magazine.

Working with various connections he made at LIFE, Thompson was able to gain access to interview key witnesses, many of whom he admits did not lead to any “breakthroughs.” Thompson focused on Dealey Plaza witnesses who were in a position to see the area of the Grassy Knoll during the assassination. Some of these had been previously interviewed by the Warren Commission or given depositions to law enforcement, and Thompson sought to reconcile testimony that appeared to conflict with the WC version of events. Among these were S. M. Holland, a railroad supervisor who witnessed activity behind the stockade fence overlooking the Knoll around the time of the assassination. Holland was detailed about what he saw and heard, especially what appeared to be two gunshots, along with a “puff of smoke” around the stockade fence. He ran to the location with two other rail yard workers and found numerous footprints and cigarette butts around the fence and a parked car, agreeing with what Lee Bowers saw from the switching tower. Certainly, someone was there just before the assassination. Thompson concluded that it would have been possible for a gunman to stow the murder weapon in the trunk of the car, then drive away later without detection. While this is a reasonable hypothesis for how any would-be gunman could have gotten away, it still implies a plan with a high risk of being caught.

While Thompson does acknowledge the limitations of witness testimony, he still uses them to support his conclusion on the location of a Grassy Knoll gunman. Thompson also recounts other anomalies that he encountered, including conflicting testimonies and questions about physical evidence, for example, the discovery of the evidence bullet (CE399) on a stretcher at Parkland Hospital, and the three expended hulls found in the sniper’s nest. Although these may have been legitimate questions at the time leading to his initial speculative “reconstruction” (“four shots from three locations in just under six seconds”), most have since been resolved. Nevertheless, their repetition still goes a long way toward sowing doubt in the minds of the “CT inclined.”

It was through his LIFE connections that Thompson became among the first to see and study high-resolution frames of the Zapruder Film, the now infamous 8 mm silent home movie of the assassination sequence. For several serendipitous reasons, this film of the assassination is nothing short of an evidentiary miracle. While it might appear somewhat low resolution and grainy by today’s standards (and it’s silent), it was state-of-the-art for its time, using color film optimized for outdoor sunlight conditions, possessing a large optical zoom lens, and filmed from a vantage point that could not have been better chosen.

Within Thompson’s autobiography, it was these early years that would lead to what is considered by many to be the best pro-conspiracy book to have been published, Six Seconds in Dallas. Thompson would achieve national fame, appearing on television and radio as an expert WC critic on the case. Unlike many of the first and second wave assassination buffs, who would spend time speculating on grander and grander conspiracy schemes, Thompson was focused on the Dealey Plaza crime scene, primarily areas where the WC Report findings seemed contrary to intuition. This naturally included the “single bullet theory” (i.e., a single bullet hitting both Kennedy and Gov. John Connally), but it was the fatal shot (striking Kennedy in the head, near-instantly killing him) that captured most of his attention. No one can deny that this horrific event captured at Zapruder Frame #313 (Z313) is the “climax” (as Thompson aptly puts it) of the 26-second film.

Indeed, I remember when I first saw it in 1975, not yet 10 years old, lying on the floor in front of the TV and hearing the gasps of my parents and older brothers behind me, not knowing fully what I was seeing. (Believe it or not, I had thought that Mrs. Kennedy’s climbing onto the trunk of the limo was President Kennedy being thrown back). It was seeing the sequence on TV as an impressionable kid that initially sparked my own interest. In recent years, I have given a handful of lectures on this topic before academic audiences, and I have asked for a show of hands from those who have not seen the film before showing it. Amazingly, a significant percentage of hands have gone up. When I proceeded to show the film (after due warning), I was nearly brought to tears by the renewed gasps in the room, feeling guilty for having exposed them to such a sad, tragic event, one of the darkest moments in American history.

Pertaining to the fatal shot, Thompson, true to the early buffs, continues to be fixated on the “back and the left” motion of the stricken President. Seeing the event at actual speed from Zapruder’s viewpoint, the untrained eye might get the initial impression (especially if suggested beforehand) that President Kennedy is being shot from the front. This seemed to confirm the early CBS reports that afternoon from witnesses who thought the shots came from a “grassy hill” overlooking the motorcade, which would eventually be coined the “Grassy Knoll.” These early reports (which also said that the Secret Service found a “huddled man and woman” on the top of “a grassy hill” who may have been the “would-be assassins”) were based on a handful of eyewitnesses who were closest to the limo (and who thus had the impression that the fatal shot must have come from nearby). But first impressions can often be wrong, and if there is one thing I learned from my career and education, it is that the physical world can be counterintuitive.

Consider sound waves, for example. Because sound is a wave phenomenon, identifying the source of a sound (e.g., a gunshot) is not always straightforward, as most of us know from experience. Sound waves echo off hard solid objects, are muffled by others, and, perhaps most importantly, they also bend around objects. Although we are aware of these properties of sound, they nevertheless can sometimes confound the ability to pinpoint accurately the source. This especially applies to a gunshot (more precisely, the muzzle blast) in a complex urban environment, not to mention the additional confusion from the shockwave (i.e., the “ballistic crack”) caused by a supersonic bullet.[2] Interestingly, Thompson seems to understand this and correctly points out that the earwitness testimony (suggesting the shot came from the Knoll) is not necessarily reliable.

Thompson understands the primacy of evidence in the case, and that one cannot willy-nilly throw out evidence one does not like. Thompson is quite capable himself of thoroughly debunking the more fringe “conspiracy theories,” such as the preposterous “Zapruder Film alteration” that has metastasized over the conspiracy blogosphere and social media. Zapruder Film alterationists contend that the film was “altered,” an example of taking layers and layers of ad hoc assumptions to their extreme, self-contradictory conclusions.

Here Thompson is correct, of course: The extant Zapruder Film is authentic photographic evidence of the crime.[3] It has been confirmed authentic by photographic experts, for example, noted Kodak film expert Roland Zavada., who has unambiguously asserted that “there is no detectable evidence of manipulation or image alteration on the Zapruder in-camera-original [film] and all supporting evidence precludes any forgery thereto”.[4]

The technology simply did not exist in 1963 to make undetectable alterations to 8 mm reversal film, and even today, it would not be trivial. We are not talking about using Photoshop to alter an electronic JPEG image—we are talking about making physical alterations to the extant physical film itself. From a common-sense perspective, when one considers, for example, that the image of JFK’s head on the film is about the size of the point of a pencil, and that there would not be a second chance to “Undo (Ctrl+Z)” a mistake, one might imagine just how far-fetched this scheme would be. Sorry, but no. If would-be conspirators (operating in the real world) wanted to conceal damning evidence in the Zapruder Film, they would have simply sought to destroy it, had there been an opportunity. But ultimately, there never was an opportunity for them to get their hands on it, as David Wrone, Thompson and others have documented in the chain-of-custody. It should go without saying that alteration would also require “back-engineering” the entire assassination sequence so that the alterations would conform to a coherent, predetermined assassination cover story.

But even with these independent lines of proof, from a purely philosophical point-of-view, objection to “alterationist” nonsense has an even more fundamental underpinning: If the Zapruder Film was “altered,” then how do we even know that JFK was assassinated? What if the whole thing was an orchestrated hoax, like the “Moon Landing Hoax”? And before somebody objects “but the media reported it,” “the witnesses and ER doctors saw it,” “they performed an autopsy,” “they buried him in the ground in Arlington Cemetery during a state funeral,” etc. — sorry, but that train has left the station. Once we start denying key pieces of evidence (e.g., the Zapruder Film, autopsy materials, physical evidence, etc.) without ironclad proof (i.e., other more fundamental evidence), we can then deny all the evidence on the same grounds.

And once we have descended to that point, we no longer have any basis for investigation or argument, nor any basis for “believing it”—we are simply wasting our time debating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.

Alas, the Zapruder Film is indeed authentic (as is the other primary evidence) and it shows precisely (and gruesomely) how the 35th President was brutally shot to death in Dealey Plaza. On these points, Thompson and I are in full agreement. Nonetheless, as will be seen, this discussion of the Zapruder Film is germane to what we find later in the book.

On Shooting Melons... or Coconuts… or Reasonable Facsimiles

In the concluding chapter of Part I Thompson reveals the origins of what would be a lifelong (and apparently bitter) feud with physicist Luis Alvarez that will manifest itself throughout the remainder of the book. Fellow scientists, engineers and mathematicians out there will understand what a profound achievement it is to receive the Nobel Prize in physics, as Alvarez did in 1968.

Like many of us, Alvarez would take keen interest in the case. For him it was apparently kindled by the November 1966 LIFE magazine article, titled “A Matter of Reasonable Doubt,” which Thompson had contributed to and which featured large blown-up full-color frames from the Zapruder film. Alvarez was initially interested in the effect of camera panning error in creating bright streaks from shiny reflective surfaces such as the chrome window frame, hypothesizing that these frames could be indicators of startle responses Zapruder may have shown as the result of gunshots. Based on his quantitative “jiggle” analysis, Alvarez concluded that there were only three shots fired in Dealey Plaza (and he would go on to assert that there was no conspiracy).

Given his status, Alvarez was given airtime on CBS News (hosted by the most trusted man in America, Walter Cronkite) to make his case in defense of the Warren Commission. Thompson subsequently came to his own conclusion that Alvarez was not forthcoming about his “jiggle analysis” and had overreached on the conclusion of three shots fired, given that there were more than three “jiggles” evident in the film, which, in all fairness, Thompson had a point on. (Alvarez handwaved that one of them was caused by Zapruder’s startle response to the Secret Service siren.) He wrote Alvarez a letter that by his own account was “sloppy” and “decidedly lacking in tact.” If it were anyone else, Alvarez probably would have dismissed the letter as coming from a nut and tossed it in the proverbial recycle bin (which is what Thompson apparently expected). But Alvarez felt compelled to respond in kind, albeit as if he were swatting an annoying fly.

But Thompson would find out from Paul Hoch, then a graduate student under Prof. Alvarez (and a well-respected first-generation assassination researcher), that he apparently had gotten under Alvarez’s skin more than the physicist let on. One gets the sense that Thompson felt a certain sense of satisfaction, given his description of the entire “scuffle” with the Nobel Laureate as being “comical,” and Hoch ultimately acknowledged that Thompson was probably right about the Secret Service siren. Undoubtedly feeling emboldened in “the brash confidence of youth” and Hoch’s siding with him, Thompson then decided to “turn the knife” by sending Alvarez another letter, this time carefully typed and gloating over the fact that Alvarez’s associate Paul Hoch had agreed with a “cheeky assistant professor of philosophy” over the internationally recognized physicist.

But it wasn’t Hoch’s opinion that was the “knife turner,” but rather Thompson’s not-so-subtle insinuation that Alvarez had “cherry-picked” his data, a decidedly unethical and unprofessional practice in science. I was dumbfounded when I read this, and I can only empathize with how Alvarez might not have taken too kindly to the gall in the accusation. But rather than toss it into the recycle bin with the first letter, breathe, count to ten, and then let it go, he felt the need to respond, basically explaining (correctly) that one of the main things a scientist does is “to decide which of the evidence he sees must be wrong and must be ignored.” Or, in other words, to distinguish meaningful “signal” from irrelevant “noise”. [5]

While he tries to brush off his encounters with Alvarez as somehow “funny,” Thompson obviously did not like Alvarez’s dismissive tone in his replies. But I would have informed him that such a response, if any, would not be atypical from a physics professor, and that it would be best not to take it personally. It may have been one thing for Thompson to challenge Alvarez on his own turf as a philosophy professor, but there is a certain level of presumptuousness in advising a Nobel Laureate in physics on the topic of science.

However, dirty laundry aside, we are told that the private communications with Alvarez establish “a context for understanding Alvarez’s thinking and methodology,” and unfortunately, we are not talking about science here, but rather his establishment worldview. At best, this tactic is ad hominem, and at worst, it’s gossipy. But Thompson’s fixation on politics evident throughout this book is telling in its own right. Yes, scientists and investigators may have private political opinions, but the establishment of facts in a crime has nothing to do with “politics.” That is the entire basis behind the scientific method and our post-Enlightenment justice system. Yet the real beef comes with Alvarez’s “second, and far more influential, theory,” namely the “jet effect,” the explanation that Alvarez proposed to explain the “back and to the left” motion of President Kennedy, and thus a direct challenge to Thompson’s book Six Seconds in Dallas.

My own backstory on this topic is relevant since many buffs treat the “jet effect” as an explanation conjured up by Alvarez. I had never heard of Luis Alvarez (or the term “jet effect”), until about ten years ago, when, as an anonymous commenter on various blogs, I was offering up my own (at that point qualitative) “theory” that JFK’s “back and to the left” motion was due to a recoil effect (aka, “jet effect”). At some point, another anonymous blogger brought to my attention a physicist named Alvarez and his 1976 paper on the “jet effect.” Up until that point I had read the WC Report (inspired by seeing Oliver Stone’s movie JFK), but I had read little else on the case due to the pressing demands of graduate school and early career, so at the time I was unaware of post-WC developments.

Some 15 years earlier I was in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison when it first independently dawned on me that the explosive wound seen in the Zapruder Film would cause a recoil of JFK’s head—and the more I thought about it, the surer I became of it. I remember an incident in a classical mechanics class when we were studying inelastic collisions. Someone asked a question about gunshots and the TA said that a body struck by a bullet would move very slightly in the direction of the bullet as an inelastic collision. Although I was normally a quiet student, I spoke up saying that no, the bullet would actually pass through and create a much larger exit wound on the other side, and this would cause the body to move toward the shooter… The TA, surprised by this response, pondered it for a moment, and then thoughtfully said, “hmm, that’s true...” And the professor, uncomfortable with the gory direction the discussion had taken, cleared his voice, interjected something to the effect of “okay, that’s enough of that subject...” and then moved us quickly on to the rest of his lecture.

Of course, I have since learned that gunshot wounds are a bit more complicated than that, and that “jet effects” from such wounds are probably exceptions to the rule. But the point I wanted to empathize here is that the very same idea came to me without ever hearing of Alvarez. That is because the “idea” is not really about him or me—it’s about how the physical world behaves. Upon learning that he published this idea a good 20 years before I “discovered” it, I was disappointed, for I honestly thought I had stumbled upon a unique and original idea. But I was also comforted in the realizations that (1) I was not out in left field with my physical intuition, (2) Alvarez’s approach was pedagogical in nature and thus there was room for a more detailed independent analysis, and (3) in the interim, “CTs” had gotten comfortable in rejecting Alvarez as a some sort of one-off “government shill,” and thus there would be ample rationale in revisiting it anew (which I eventually got around to publishing in the journal Heliyon in 2018 [6]).

Alvarez arrived at his “jet effect” theory after obtaining a copy of Six Seconds from Paul Hoch. He studied the figures showing the change in position of JFK’s head and came to the realization, as I did, that there must have been a real force [7] at play in driving JFK’s body backward in the limousine. But he was not convinced of Thompson’s “near simultaneous gunshot” hypothesis. Given it was a journal directed to physics educators, Alvarez relates how he worked out the essence of his theory on “the back of an envelope” while on conference travel. This is not atypical for a physicist to keep things as simple as possible, and using simple conservation of energy and momentum arguments, he was able to deduce that a recoil of a sufficient magnitude would be theoretically possible given certain assumptions.

As a professional colleague, Hoch recommended that Alvarez perform some sort of experimental test that “could demonstrate the retrograde recoil on a rifle range, using a reasonable facsimile of a human head.” They proceeded to carry out such experiments, trying different targets, but ultimately deciding upon a taped melon as the best “facsimile.” Hoch noted that the melons consistently exhibited a “retrograde motion” toward the shooter, and Alvarez thus was able to demonstrate that a recoil effect is indeed possible.

Through his correspondence with Paul Hoch, who shared a write-up of the melon experiments with other researchers, Thompson would find a beachhead to launch another “cherry picking” accusation. Hoch simply noted, legitimately once again, the limitations of the melon experiments. Among other things, the shell of a melon is much softer than a skull, and it will thus present much less resistance to the projectile passage. The upshot of this is that the bullet would transfer practically none of its forward momentum to the target, and thus there would be no forward impulse (discussed more below) for a “jet effect” to overcome. While this is a legitimate point, it misses the point of the experiments. In Hoch’s own words: “It should be emphasized that we did not attempt to simulate the conditions of the assassination, but only to show that a recoil towards the gun is physically possible…” Q.E.D.

During the course of the “melon experiments,” Hoch also observed the following: “Although taped melons consistently showed the ‘rocket’ effect, different kinds of targets reacted differently.” I would also venture to add that identical targets would react differently depending on where precisely they were hit, as well with different firearms and ammunition. Thus, the point of the “melon experiments” is not to demonstrate that recoil effects are a universally observed behavior of “head shots,” but rather that a bullet can produce such an effect in a “reasonable facsimile.” Of course, Thompson disputes this, claiming that “Hoch’s point is obvious. A taped melon is in no way ‘a reasonable facsimile of a human head’.” Thompson is free to have his opinion about what a “reasonable facsimile” is, but Hoch’s point was anything but. According to him: “We do feel a taped melon is not an unreasonable simulation of a person's head…” [emphasis mine]

Thompson uses the melon experiments along with a perceived “political bias” (which is always something defined relative to one’s own bias) as a cudgel to attack Alvarez and accuse him of “cherry picking” data because not all targets behave as the melons did. But that has never been the point. The point was to show that it was quite possible, thereby providing a physically plausible counter-explanation.

But regardless of Alvarez’s melon experiments, or subsequent experiments conducted independently by Dr. John Lattimer in the 1970s and more recently by ballistics expert Luke Haag, a recoil effect of some magnitude had to happen (following the initial forward impulse) given the directional mass expulsion observed in Z313, even if it were the only known case of the phenomenon, because it is an inescapable consequence of momentum conservation. The only question is, could it have been sufficient enough to cause “retrograde motion” by overcoming the initial 5 cm (2”) forward impulse brought on by the transfer of momentum by the bullet to the head? And the quantitative answer to that question is arguably “yes”. [8]

One gets the impression that Thompson never got over the fact that Luis Alvarez, undoubtedly one of the greatest scientific minds of his time, would publish a paper in a reputable journal that would offer a plausible scientific counter-explanation for JFK’s “rearward lurch.” But notably, while Alvarez makes extensive reference to Thompson’s book in his paper, at no point does he impugn Thompson’s integrity or work. Indeed, when I eventually read Alvarez’s paper, I never got the slightest inkling that there was any bad blood between these two men. Instead, we have Alvarez saying things like “[Thompson’s book Six Seconds in Dallas] is beautifully printed, with excellent photographs and carefully prepared graphs.” I had expected that Thompson would have since changed his mind on his original conclusions given what we have since learned.

But alas, as Dale Carnegie once said, “a man convinced against his will, is of the same opinion still.”

Part II: Aftermath—The 1970s

In Part II, Thompson focuses on developments during the 1970s following the publication of his book, including his meeting Robert Groden and his role in the unauthorized showing of the Zapruder Film on ABC’s Good Night America program (hosted by Geraldo Rivera and aired on 6 March 1975). The Zapruder Film’s airing on national television was a game-changer event, bringing the JFK “conspiracy theory” to many Americans for the first time, influencing public opinion about the crime, and leading to the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) government reinvestigation of the case in 1976.

The HSCA “Acoustics Evidence”

It was around this time that Thompson had decided that being a college professor of philosophy wasn’t really for him. As he was becoming disillusioned with his academic career path, Thompson coincidentally found himself invited by the HSCA to join a group of authors (primarily WC critics) gathered in Washington, DC to provide guidance to Chief Counsel Robert Blakey. Thompson then recounts the origins of what would become a decades-long pursuit, referred to by some as “acoustics evidence” for a gunman on the Grassy Knoll.

The acoustics evidence in question refers to recordings of the radio transmissions of the Dallas Police Department (DPD) that occurred before, during and after the motorcade. The group of WC critics summoned by the HSCA had been discussing possible conspiracy scenarios (which, surprisingly, Thompson admits to having no interest in, even nodding off at one point), when the conversation turned to the Dallas police, at which point Mary Ferrell as an aside brought up the “police tapes,” and that apparently there were some out there (specifically Gary Mack) saying that one could “hear” 7 to 8 gunshots on them. And yes, the original claim was that one could actually hear the gunshots on the recordings. This is a relevant point to keep in mind as we proceed in the discussion of this topic.

At this point, a brief explanation is in order for those unfamiliar with the DPD radio recordings (as I was, not too long back). Although this topic was something that I had been vaguely aware of from my earlier literature review of the Kennedy assassination (e.g., the book by Larry Sabato, along with Vincent Bugliosi’s treatise, Reclaiming History), it was the claims in Last Second that forced me to dive in more, and it is quite an onion to unpeel. In 1963, the Dallas Police routinely recorded the radio transmissions of their police force. They broadcast over two FM channels, the first channel (Channel 1) being the normal channel used for day-to-day activities, the second being a supplementary channel (Channel 2) for special events such as the Kennedy motorcade. There were separate recording systems for each channel, a Dictabelt and a Gray Audograph for Channels 1 and 2, respectively. The peculiar characteristics of these two devices become important in the analysis of the recordings, notably an automatic sound activation so that the devices would record only when there was a broadcast, switching off during periods of radio silence.

The police radios operated in typical fashion: A police officer would press a button on the microphone to “talk” (transmit his voice) and release the button to “receive” (to hear other broadcasts on the channel). During the time period of the motorcade, the current times would be broadcast occasionally by the dispatchers to annotate the time on the recordings. The radio system also featured an automatic gain control (AGC) whereby loud sounds would be dampened (reduced) and soft sounds would be amplified, thereby maintaining a relatively constant volume (amplitude).

It turns out that it was not uncommon for microphone buttons to get stuck in the “on” position, and as luck would have it this happened to one of the motorcycle police officers, which led to a continuous broadcast for a period of about five minutes on Channel 1. Although Channel 2 was the channel for motorcade communications, some of the buffs hypothesized that the open microphone may have originated from a motorcycle in the motorcade located in Dealey Plaza (for some reason transmitting on Channel 1 in violation of protocol) at the time of the shooting, thereby picking up the gunshots. This led the HSCA to pursue the matter further, and one of the investigators was able to obtain “original tapes” from a former DPD assistant chief. These were then submitted for analysis, first to a team led by Dr. James Barger, a scientist with Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), then on to Prof. Mark R. Weiss and Ernest Aschkenasy (W&A) at CUNY, all three being experts in acoustics.

The analyses that BBN and W&A performed involved matching waveform impulse patterns obtained from the Channel 1 open mic recording to test patterns (including echoes) obtained from experimental (BBN) and simulated (W&A) setups. The experimental setup by Barger’s BBN team was conducted onsite in Dealey Plaza, with an array of microphones, and gunshots (rifle and handgun) fired from two locations, the Texas School Book Depository (TSBD) Sniper’s Nest and the Grassy Knoll. Barger found a match to the DPD Channel 1 recording with the Grassy Knoll test shot with a 50% statistical confidence. But W&A found a simulated Grassy Knoll waveform match (with 95% confidence) from manual calculations based on a model of Dealey Plaza (N.B., the model was not a computer model, but rather used a hard-copy map of Dealey Plaza). Specifically, the match with the Grassy Knoll was found for a simulated open mic located at a specific location near the intersection of Houston and Elm.

It was the latter finding that led the HSCA to an eleventh-hour amendment to its original conclusion of a lone gunman (affirming the WC Report), to include a second gunman on the Grassy Knoll (at the location that Thompson identified previously based upon his interviews with eyewitness S. M. Holland) who fired one shot that missed the limo completely, thus concluding that President Kennedy was “probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.” So, while the HSCA concluded “probable conspiracy,” their scenario was based upon the acoustics evidence and was at odds with Thompson’s (and others’) scenario of a frontal impact to JFK’s head. Thompson relays to us that the HSCA’s conclusion was constrained by independent findings from Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) that was performed by Dr. Vincent Guinn on the bullet fragments from the crime scene. Guinn had determined that it was “highly probable” that the fragments in Gov. Connally’s wrist were from the “stretcher bullet” (CE399) found at Parkland Hospital, and that the fragments from President Kennedy’s head were from the same bullet as the fragments found in the limousine, thereby providing strong evidence that only two bullets caused all the wounds.

In his book, Thompson does a decent job of accurately relaying all this background information to the reader. The DPD radio recording system, with its primitive recording media (Dictabelt and Audograph), automatic shutoff and AGC features, was designed for recording and monitoring routine police radio voice communications. The system was designed for recording spoken radio communications over the course of an entire day, not for high-fidelity forensic sound reproduction of a 10-second crime sequence during an outdoor motorcade.

As an analogy, one might think of security camera video footage, which is generally poor resolution, black-and-white, and wide angle—a setup optimized for routine monitoring for criminal activity over the course of an entire day, but not the positive identification of perpetrators. The same goes for the DPD radio Dictabelt and Audograph audio recordings, which, beyond the recorded content of spoken words, are considerably more primitive in terms of information content by comparison. The BBN and W&A teams nevertheless argued that the Channel 1 open mic recording could be used to identify gunshots in Dealey Plaza.

Parts III and IV

III: Breaking the Impasse—The 2000s

IV: The Signal in the Noise—2013–2017

The latter two parts of the book mark the transition from the author’s retrospective account of his involvement in the case (spanning his work up through the 1970s and the HSCA) to his subsequent renewed interest beginning in the mid-2000s, which is traced back to the 1982 National Research Council (NRC) Ad Hoc Committee on Ballistic Acoustics, along with a subsequent peer-reviewed 2001 paper published by Dr. Donald Thomas [9] in the UK journal, Science & Justice.

The prestigious NRC panel was commissioned to examine the HSCA findings involving the DPD recordings and included a number of recognized experts, including Luis Alvarez. Thompson spends an entire chapter in Part IV (Chapter 17) portraying what might be characterized as his ultimate triumph against the late physicist-nemesis, whose work had left him in a “funk” in 2013 (when Last Second was originally planned to be published) because of the debunking of the acoustics evidence by the NRC panel. Of course, Thompson then proceeds to impugn the ethical character of Alvarez as well as the entire panel, calling it “unvarnished advocacy,” and insinuating in Chapter 20 that they were guilty of criminal malfeasance. This sets the stage for later in Part IV, where Thompson then argues that the “acoustics evidence” has been vindicated despite the NRC conclusions.

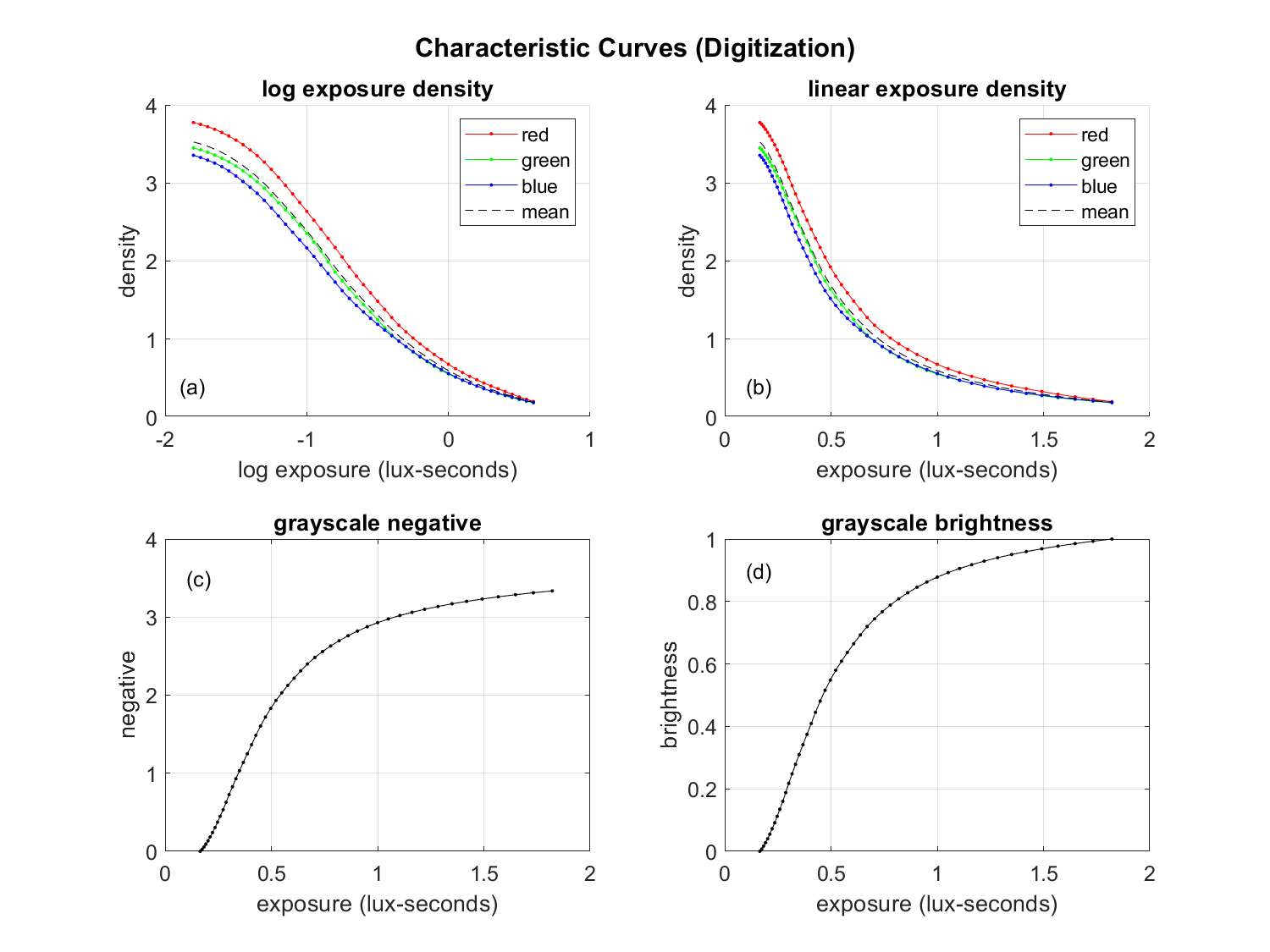

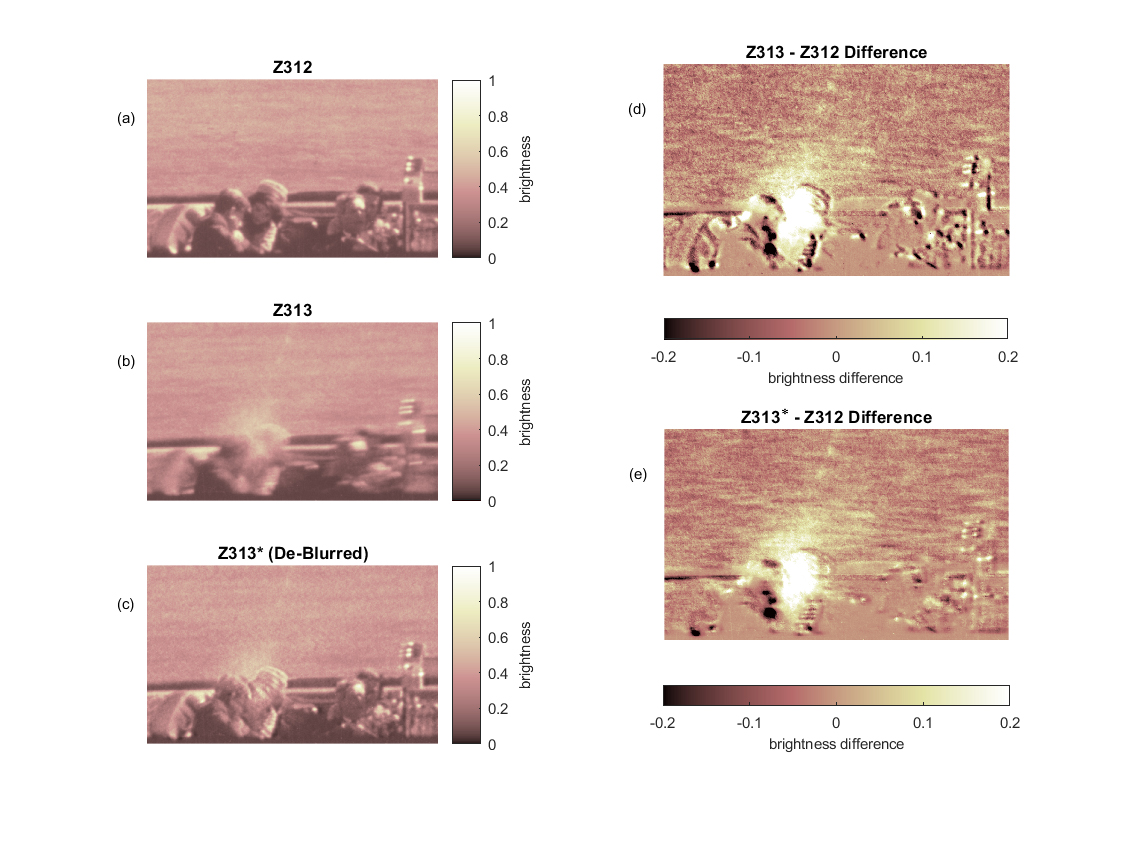

By this time, Thompson had established his own Private Investigator practice, the days of being a professor long behind him. The second half of the book leads the reader to Thompson’s revised scenario of the crime, which, like the original scenario, involves an unnamed conspiracy with an unknown gunman firing from the Grassy Knoll and hitting Kennedy in the head at Z313. However, the novelty of Thompson’s revised scenario is his claim that there was a second shot to the head (from the rear) at Z327–Z328, following a frontal shot at Z312–Z313; this scenario is based upon four revised “puzzle pieces”. [10] Two previously accepted puzzle pieces (evidence) are tossed out of the box and replaced by two new pieces that conveniently fit Thompson’s puzzle as follows:

- Tossed out: The NAA findings that only two bullets caused the wounds of both Kennedy and Connally.

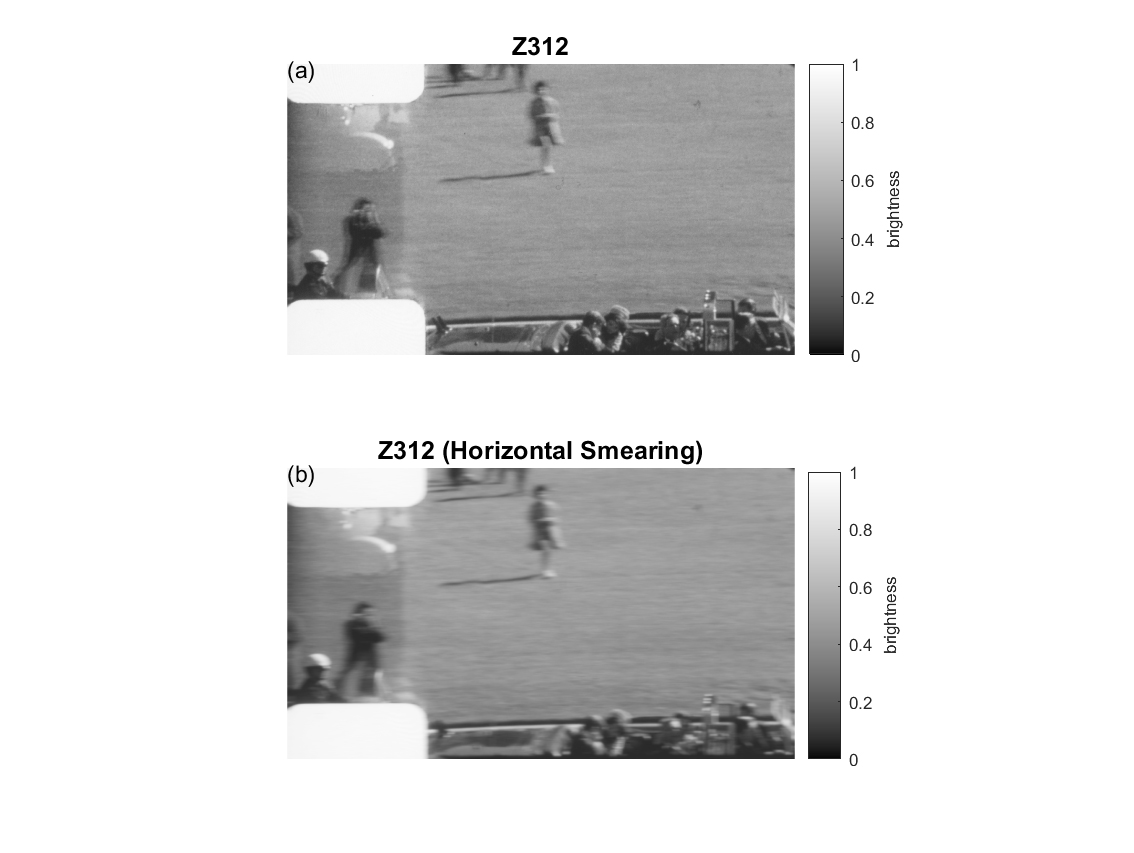

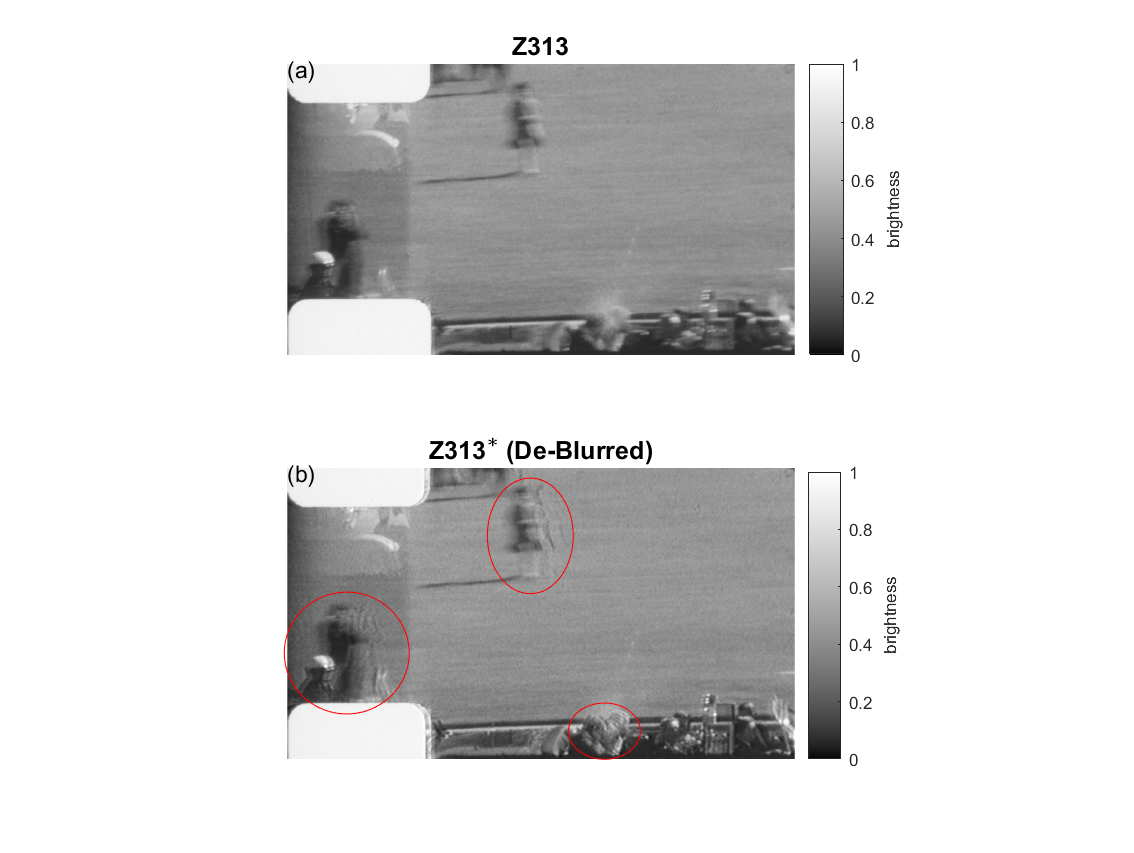

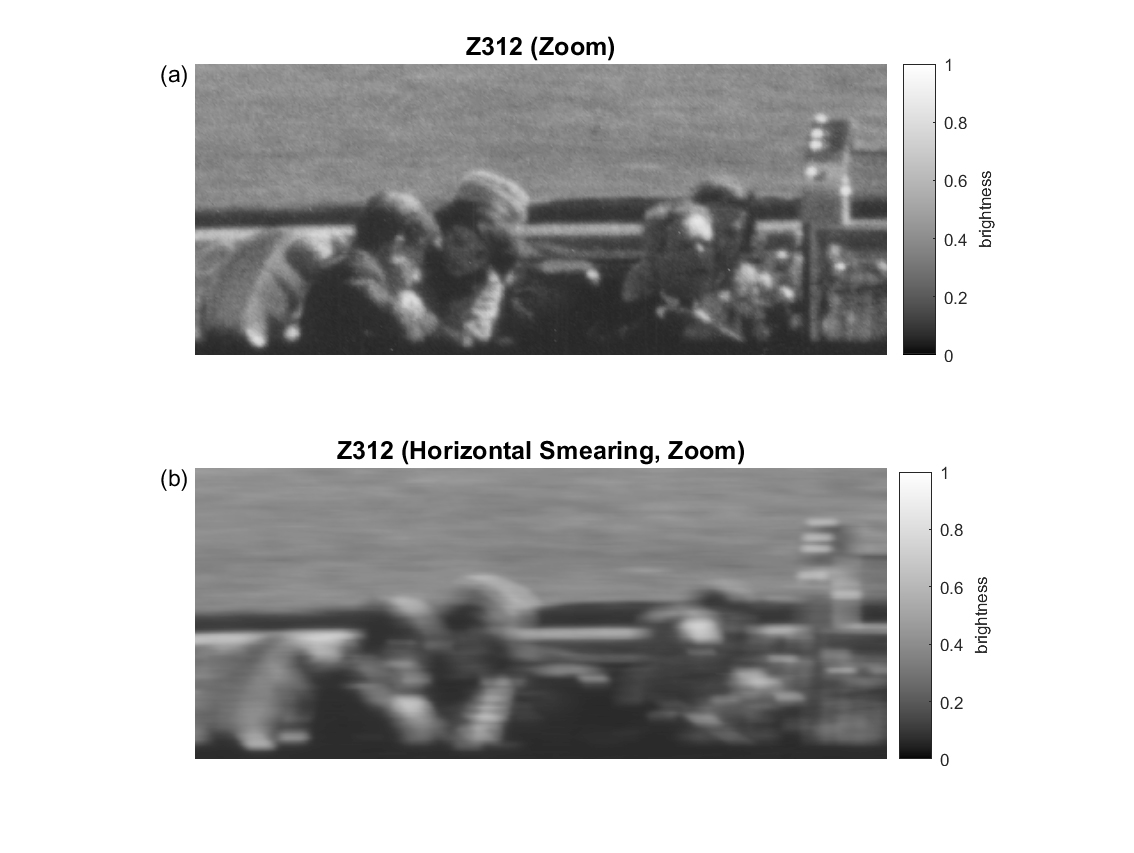

- Tossed out: The observed forward snap of Kennedy’s head in Z312–Z313 (indicative of a shot from behind) due to motion blurring of Z313 (i.e., a “reinterpretation” of these frames as a “optical illusion”).

- New piece: A reinterpretation of the 1967 Zapruder Film measurements as evidence for a late Z327-Z328 “head shot” along with an attendant reinterpretation of nearby eyewitness testimony.

- New piece: A resurrected interpretation of the DPD recordings as “acoustics evidence” of two shots to the head in “the last second” of the Zapruder Film sequence.

On its surface, the high-level approach of Thompson’s presentation has a certain allure given its symmetry and the metaphor of a puzzle. I too have considered the solution of this case as analogous to the solution of a puzzle, whereby the full picture comes together not by any single piece (of evidence), but rather the aggregate whole of all the pieces.

Other than the questioning of the NAA findings, those pieces crumble upon closer scrutiny. We will consider these points individually, with more attention given to the “blur illusion” (#2), discussed in the last section. [11]

The first puzzle piece to be tossed (#1) is the NAA finding that there was physical evidence of two, and only two, bullets found at the crime scene. There has apparently been some degree of legitimate dispute about the NAA findings of Guinn. However, counterarguments have since been advanced from forensic experts such as Larry Sturdivan (cf. The JFK Myths) and Luke Haag. [12] Lacking personal expertise, I shall remain, for the time being, agnostic on Guinn’s findings. Sturdivan and Haag are not to be easily dismissed; Haag has indicated that he has been looking into modern methods such as Multiple Collector-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (MC-ICPMS), which he wrote: “goes far beyond what Dr. Guinn, or anyone else using NAA in the 1960s and 1970s” would have been able to achieve. Thus, I would not consider it justifiable for this “puzzle piece” to be tossed just yet. The case for a lone gunman does not hinge on this evidence, and despite the uncertainty surrounding the only-two-bullets conclusion, no positive NAA evidence of a third bullet has been found.

A Rear Shot to the Head at Z327–Z328

The second puzzle piece to be tossed is the one-frame Z312–Z313 forward snap of President Kennedy’s head. However, the first “new” puzzle piece that Thompson introduces (#3) replaces it, namely a reinterpretation of Thompson’s original (Thompson-Hoffman) 1967 Zapruder Film measurements. Thompson credits this “reinterpretation” to “another brilliant non-professional” named Keith Fitzgerald, who pointed out to him at a meeting in 2005 that “according to [Thompson’s original] measurements, JFK’s head moved forward 6.44 inches between frames 327 and 330,” and that apparently the head wound changes during this timeframe. When I first read this, I wondered what they could be talking about, for I did not recall seeing anything like this, either in the film or in the Thompson-Hoffman data. As Thompson himself says in the book, the “climax” of the film is the fatal shot at Z313. I do not recall any prior suggestion of another gunshot wound to the head occurring after Z313.

One good reason for this, of course, is that when one views the film at full speed, one simply does not see another gunshot effect after Z313. We clearly see a shot hitting both Kennedy and Connally at the same time around Z224–Z225, then the fatal shot at Z313, but there are no other indicators of gunfire wounding the limo occupants. It’s really that simple.

The HSCA had already considered this scenario of “the fourth shot” from the Texas School Book Depository (TSBD) sniper’s nest (based on the acoustics evidence) striking Kennedy in the head at Z327–Z328. However, they concluded, based in part upon a preliminary trajectory analysis, that “it is highly unlikely that the head wounds were inflicted by firing a bullet from the [TSBD] southeast window [sniper’s nest] that impacted [JFK’s head] at the time of Zapruder frame 327.”

The frames in question occur very shortly after the Z313 kill shot and Kennedy has already rebounded off the back seat after a neuromuscular spasm. His body has gone visibly limp and has slumped over sideways onto Mrs. Kennedy, who, understandably, has just begun to react in terror. When discussing these details, one should keep in mind that all this happened in under one second (indeed, this is the raison d'être for the eponymous “Last Second in Dallas”).

The President’s head had been shattered by a temporary cavitation wound produced by the passage of a high-energy projectile, and its “contents” were still pulsing out due to restoring force oscillations. As Marilyn Sitzman (who was standing with Zapruder) pointed out (and Thompson quotes): “And we could see his brains come out, you know, his head opening.” Or as witness Bill Newman told Thompson in his interview with him: “When he was hit, I was looking right at him, and of course immediately I knew he was shot… then blood, gook just started bulging out...” and Thompson himself confirms: “What [Newman] was describing was exactly what the film shows.” Mrs. Kennedy, in shock, instinctively tried to climb out of the limo before Secret Service Agent Clint Hill got her safely back into the car.

Thompson bases this conjectured late shot on his 1967 data, which shows a multiframe “forward lurch” following the multiframe “rearward lurch,” along with “changes” to the head wound during these frames that he tries to illustrate with annotated high-resolution color prints of the frames. As alluded to above, the observed changes to the head wound are the result of the lingering effects of Z313, which occurred less than one second prior. The skull contents were literally still undulating due to the temporary cavitation wound and were thus pulsing out and falling to the floor under the force of gravity. Another gunshot wound at this point would exhibit a one-frame anomaly or impulse of some sort. Thompson claims “any subsequent impact would cause no explosion” because “the pressure vessel” of JFK’s head “no longer exists” (after Z313), but this is simply an incorrect understanding of the mechanics. The “explosion” is not due to the static pressure of the brain inside of the skull cavity (as in a pressurized cylinder of gas)—it is due to a transient pressure wave generated within the tissue by the deposit of kinetic energy (KE) from a high-speed projectile disturbance, somewhat analogous to a rock thrown into a pond.

Yes, another “explosion” would in fact happen from a high-speed bullet, provided that the bullet deposits its KE during passage. Thompson suggests that JFK’s aggregate forward motion over these multiple frames is due to such a projectile, but like the earlier “rearward lurch,” both the timescales and the magnitudes are nowhere near consistent with the effect of a high-speed bullet. But let us assume for sake of argument that in one of the frames there is a forward head-snap (occurring on just the head, mind you, not the entire body) of the same magnitude as Z312–Z313 (that isn’t a “blur illusion,” mind you… stay tuned). That would mean that the projectile deposited its momentum, which then means that it also deposited its KE. If it were a high-powered rifle then the KE deposit would be large, thereby creating another temporary cavitation pulse, and thus another “explosion.” On the other hand, if the projectile were to pass through meeting little resistance without causing noticeable temporary cavitation damage, that would mean that it did not deposit any appreciable KE, which in turn would mean that it did not deposit any momentum, and thus no “forward snap.”

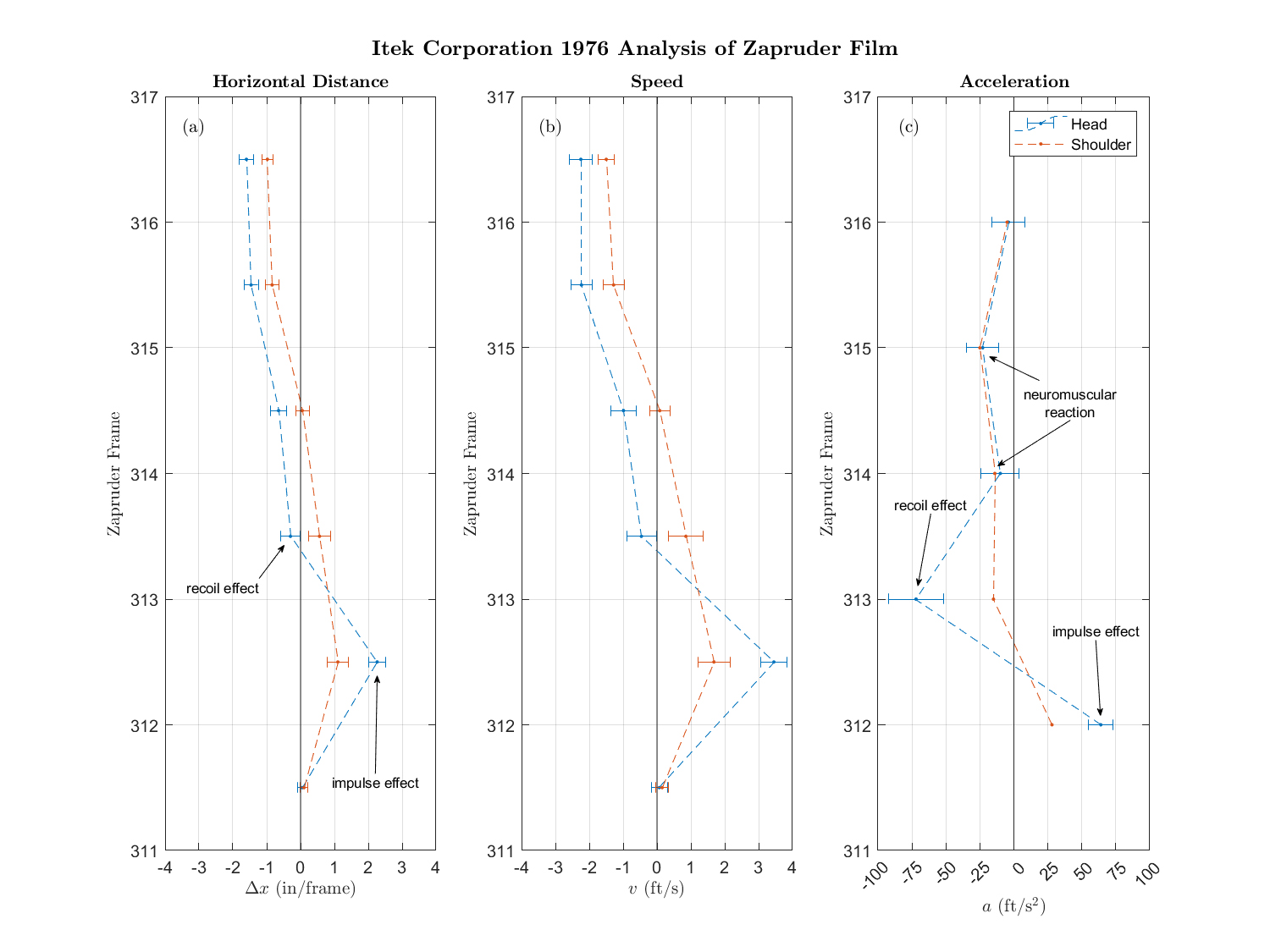

Getting back to the actual Thompson-Hoffman data: When looking at any type of data, one must always bear in mind what exactly it represents, and in this case, it is simply the frame-by-frame position of the back of the President's head relative to the top of the back seat. Around the time of the fatal shot (Z313), JFK is still seated upright (albeit leaning slightly forward and to his left) and positioned lateral to Zapruder’s field-of-view. Further, there is nothing interfering with the free motion of his head on his neck. These circumstances fortuitously allow one to perform a kinematic analysis of his head in these frames (along with the top of his shoulders, as was performed by Itek Corp). By the time we get to the later frames in question (Z327–Z330), the President has gone completely limp and is slumping over sideways away from the camera onto his wife, who herself is in the process of reacting. JFK’s motion during these frames is not due to a near-instantaneous interaction of his head with a high-speed projectile, but rather the interaction of his lifeless body with the backseat, Mrs. Kennedy, and the force of gravity.

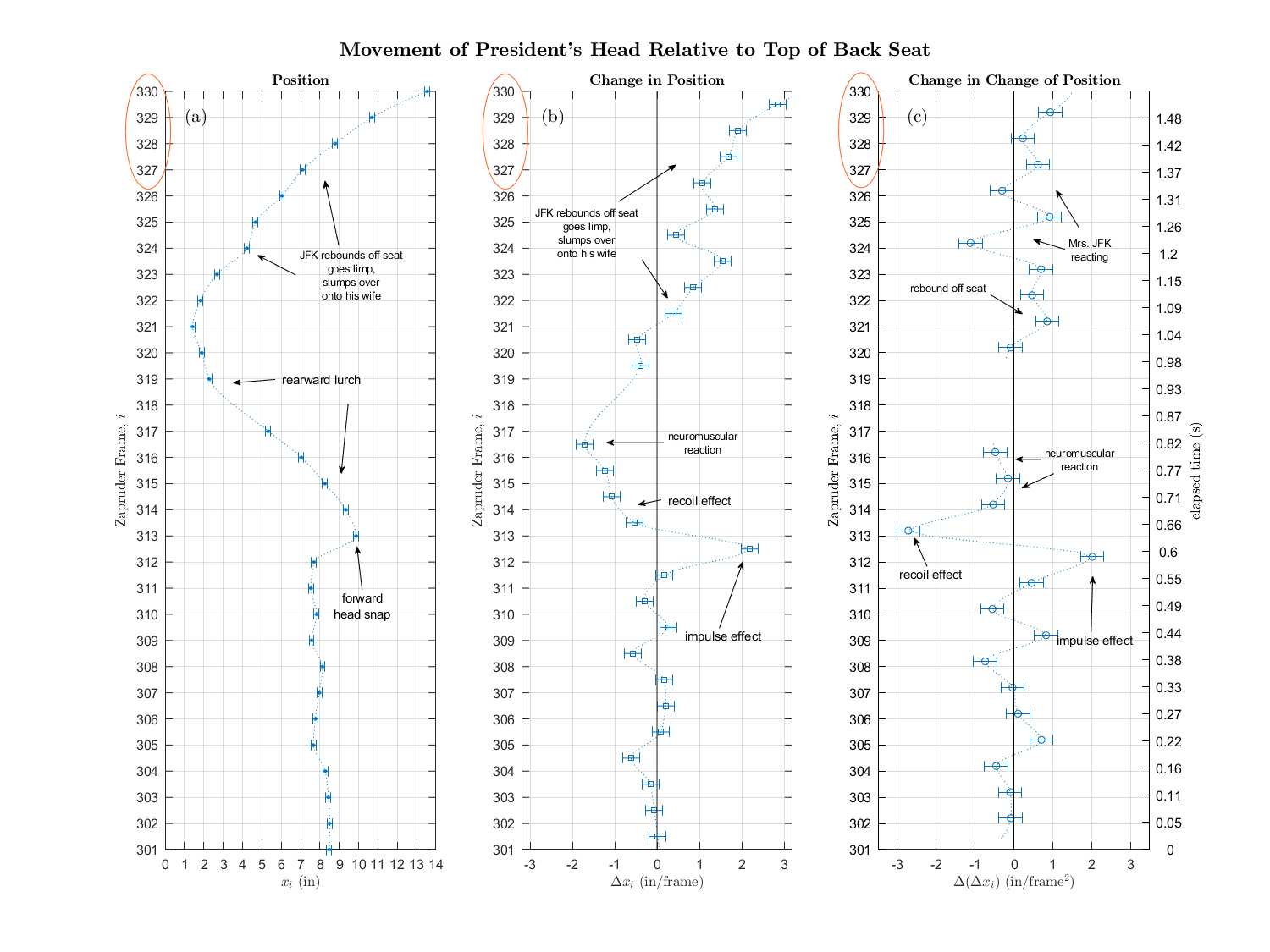

Figure 1 includes the Six Seconds data, as shown there, with the addition of Z330 and graphs of velocity and acceleration. There is no indication of a shot at Z327–Z328. The forward motion of “6.44 inches between frames 327 and 330” is part of a smooth curve already in progress (Fig. 1a). This multi-frame forward movement was initiated at Z322 by the rebound of JFK’s lifeless body off the rear seat (after a neuromuscular spasm), followed by his falling limp onto his wife.

|

Figure 1 - Motion of President Kennedy’s head (blue) relative to the back of the limo seat from the Zapruder Film (frames Z301 to Z330) based on data from Thompson’s Six Seconds in Dallas and plotted vertically in the same manner as in the original figure (op. cit.): (left) position of the President’s head relative to the back of the seat, (middle) first-order change in position, and (right) second-order change in position. The left y-axes denote Zapruder Frame number and the far-right y-axis denotes elapsed time in seconds (rounded to the 2nd decimal place). Error bars denote the measurement uncertainty estimate (propagated through the 1st and 2nd order differences). The red ellipses on the top y-axes encapsulate the frames referenced in the text where Thompson claims to see a second gunshot wound to President Kennedy’s head.

The Resurrection of the Acoustics

The second new “puzzle piece” is actually an old puzzle piece long thought to be discarded, namely the hypothetical acoustics evidence from the DPD recordings. And with this, we must return to peeling back the onion that I spoke of earlier. Since their emergence from obscurity by buffs in the 1970s, the DPD recordings have almost become a story unto themselves. My original disposition (circa 2018 before being introduced to Paul Hoch and others) was that the DPD recordings were long ago debunked. But for starters, a brief chronological recap leading up to Thompson’s “resurrection” is warranted.

As discussed above, the DPD radio recordings were utilized by the HSCA as “evidence” of a second gunman on the Grassy Knoll in Dealey Plaza, which led them to their eleventh-hour amendment of the original conclusion of a lone gunman. The buffs, who had been summoned for ideas by HSCA Chief Counsel Blakey, managed to entice him into pursuing an investigation that turned out to be hasty and flawed, leading to a last-minute “Grassy Knoll gunman” scenario. The conclusion was based upon waveform matches between simulated test shots and the Channel 1 Dictabelt recording.

It was a mere couple of years later that an NRC Panel (which included Nobel Prize winning physicists Luis Alvarez and Prof. Norman Ramsey, informally called the Ramsey Panel) would debunk this conclusion for a good two decades, as Thompson laments in his book. The Ramsey Panel discredited the DPD recordings as “acoustics evidence” largely based upon a finding by Steve Barber, a musician who had an ear for audio recordings. Barber (with his friend Todd Vaughan) was able to make out an instance of “crosstalk” of a Channel 2 broadcast onto the Channel 1 open mic recording during which time the HSCA claimed the gunshot impulses occurred. The crosstalk in question was broadcast by Sheriff Bill Decker about 1 minute (according to the Ramsey Panel) after the shots were fired: “hold everything secure until the homicide and other investigators can get there… [to the railroad overpass].” This particular crosstalk instance has since been called “HOLD” for short.

Because it is known that HOLD was broadcast on Channel 2 well after the shots occurred, that meant that the suspect impulses on Channel 1 could not have been gunshots due to the timing. Barber shared this information with the Ramsey Panel, who would eventually conclude the same after rigorously confirming that the HOLD signal on Channel 1 was indeed the Decker broadcast on Channel 2. This should have been the nail in the coffin for the “acoustics evidence,” and for all intents and purposes, it was.

But alas, some twenty years later, out of the blue there appeared a paper in the UK forensic journal Science & Justice, which would receive mainstream media attention, thereby overnight “resurrecting” the DPD recordings. The article’s author was Donald Thomas, a research entomologist employed by the USDA. Thompson would learn about the article in the Washington Post (26 March 2001), and 9 months later he would arrange to meet up with Thomas.

As with others that he agrees with, Thompson takes a personal liking to Thomas, and he paints an agreeable portrait of a gracious, thoughtful, soft-spoken man of a few words. Thomas would go on to publish a 700+ page pro-conspiracy apologia in 2010 entitled Hear No Evil: Politics, Science & the Forensic Evidence in the Kennedy Assassination, which, with its gratuitous ad hominem attacks and politicizing generously sprinkled in with “science and the forensic evidence,” does not leave this impression.

In his 2001 article, Thomas attempted to “one-up” the Ramsey Panel with a crosstalk of his own, spoken by DPD motorcycle officer Samuel Bellah, which would counter the timing disqualifier of the HOLD crosstalk discovered by Steve Barber and argued by the Panel. The possibility of other crosstalks existing on the Channel 1 recording itself is not controversial, but here Thomas’s claim was that the timing of this particular crosstalk would trump the HOLD crosstalk and restore the timing of the Dictabelt impulses to the time of the shots in Dealey Plaza.

Enter Michael O’Dell, a systems analyst and computer scientist who took a keen interest in the science of the acoustics evidence after having read the Washington Post article that reported on Thomas’s paper. Thompson makes positive reference to O’Dell several places in his book. It was Paul Hoch and Max Holland who originally connected me with him as a subject matter expert in this area of the case. O’Dell told me how, consulting for numerous government and private firms, he became adept at problem solving in a wide variety of real-world situations, and he has very effectively applied that skill set to this aspect of the case. He had knowledge, software, and tools for manipulating audio, at which point in 2001 he dove into the deep end of the pool.

In relatively short order O’Dell single-handedly discovered a small error in the NRC Panel’s timing (for reasons having to do with the skips on the Channel 2 Audograph record). This error did not at all negate the conclusions of the NRC Panel, but it did negate Thomas’s conclusions by establishing that the impulses based on his alternative Bellah crosstalk would still be 30 seconds too late. Thomas himself would concede at that time that his “objection to the NRC’s hypothesis is largely blown away,” but it is fully understood that this was not due to any incompetence on his part; thus, while his paper’s conclusion was rendered obsolete, it was not a blemish on his reputation as an entomologist. And that should’ve been the end of it, a brief encore of the final act of the “acoustics evidence.”

But alas, it wasn’t. Thomas was not done yet; as Thompson put it: “Undaunted, Thomas soldiered on, pretty much alone and largely ignored by the media,” which is a strange statement given that neither Thomas nor Thompson were ever “ignored” by all the media. Apparently, the mining for alternative crosstalks proved to be too tempting an endeavor to pass up, and within a year, he would find another “crosstalk,” this one in accordance with O’Dell’s revised timing. The alleged crosstalk in question was from a Channel 2 broadcast just before 12:30 from Deputy Police Chief N. T. Fisher, this being “Naw, that’s all right, I’ll check it”; the purported crosstalk on Channel 1 only includes the latter 3 words “I’ll check it” (“CHECK” for short).

The surviving members of the Ramsey Panel graciously sent Thomas a pre-publication manuscript rebutting his 2001 paper (submitted to the same journal). But Thomas would promptly write them back informing them of his recent discovery of CHECK… and also indirectly accusing them of intentionally covering it up! So much for the collegial assumption of good faith, and it is no wonder they never dignified it with a reply. And Thompson doubles down on the accusation, the posthumous resentment against Alvarez (and Norman Ramsey) not at all waning.

The Ramsey Panel rebuttal paper would eventually be published in Science & Justice in 2005 (Linsker et al., 2005) [13], including a full rebuttal of the claim of a CHECK crosstalk, concluding that the words in question heard on Channel 1 were not, in fact, the same as “I’ll check it” spoken on Channel 2.

And their conclusion isn’t out in left field. My curiosity piqued, I went ahead and “checked it” myself. On the Internet (YouTube), I was able to locate both events (CHECK and HOLD) on the Channels 1 and 2 recordings:

- For Channel 1, I made use of Larry Sabato’s Channel 1 sequence: Assassination of John F. Kennedy -- Dictabelt Channel 1 Audio. The alleged “I’ll check it” (CHECK) crosstalk is at 13:57, and “hold everything secure” (HOLD) is at 14:08.

- For Channel 2, I relied on a time-corrected recording that Michael O’Dell has recently made available with motorcade locations: Kennedy Assassination Dallas Police Radio Recording, Channel 2. The alleged “I’ll check it” (CHECK) is at 6:33 and “hold everything secure” (HOLD) at 8:11.

Using headphones, I carefully listened to these multiple times, and while HOLD sounds the same on both channels, CHECK subtly does not. I was left with the impression that CHECK on Channel 1 was probably another instance of someone, perhaps the same officer (Fisher), saying “I'll check it,” but it wasn’t crosstalk with the Channel 2 transmission claimed by Thomas (similar to what the Linsker et al. paper suggested). How the words are spoken is different—there is a different rise and fall in the pitch, giving rise to a different intonation of the words.

However, Michael O’Dell, Steve Barber, and Sonalysts, whose judgment I trust more than my own on these matters, have concluded that they are not even the same words, O’Dell and Barber believing that the words are closer to “all right Chaney” (Sonalysts believing the words were “five seven”), and that they were directly spoken by someone on Channel 1 (and thus not crosstalk from Channel 2). Of course, although our ears aren’t quantitative measuring devices, they are nonetheless well-adapted to pick up on the subtleties of human speech (especially if they are trained in music and audio recordings, as with Barber and O’Dell).

And in this case, it would seem that our ears haven’t failed us, for an independent study commissioned by Larry Sabato,[14] performed by Sonalysts, Inc. (Olsen and Martin, 2013 [15]; Olsen and Maryeski, 2014 [16]), has subsequently confirmed this, concluding that CHECK was not a crosstalk from Channel 2, but rather a Channel 1 transmission on another mic, as evidenced by the presence of a heterodyne.

Thus far, in a nutshell, the “acoustics evidence” has been discredited by multiple independent lines of reasoning, each articulated and refined over the intervening decades since the HSCA hastily introduced it into their final report. The numerous rebuttals fall into several categories.

- Timing issues. This was the first and oldest rebuttal, the one discovered by Steve Barber with the HOLD crosstalk and originally argued by the 1981 NRC Panel. The hypothesized gunshot impulses on Channel 1 occurred approximately 60 seconds after the gunshots in Dealey Plaza. This has been reaffirmed in the paper by Linsker et al. (2005), and more recently (and compellingly) by both Michael O’Dell and Sonalysts (Olsen and Martin, 2013). The subsequent attempt to supplant HOLD with CHECK has been discredited for multiple reasons, including some not yet discussed here.

- Open mic location assumptions. The entire case for the acoustics evidence assumes that a motorcycle in the motorcade was broadcasting on Channel 1. Furthermore, the HSCA conclusion was based upon an impulse match that required the motorcycle with the open mic to be in an extremely specific location near the intersection of Houston and Elm at the time of the shots. These assumptions are either called into question or outright invalidated because of the following (roughly in order of increasing weight):

- The open mic was on Channel 1. Channel 2 was the channel for “special events" (which at 12:30 on 22 November 1963 was the Kennedy motorcade). All motorcycles in the motorcade would have been using Channel 2 as standard operating procedure, thus there should not have been a mic stuck open on Channel 1 within the motorcade. [17]

- DPD testimony. Related to the above, the motorcycle identified by the HSCA was that of Officer H.B. McLain, but both he and Sgt. James Bowles, key witnesses in this arena, have vehemently denied it with a number of plausible rationales that the HSCA apparently chose to ignore (e.g., see the 65 page “Endnote” #381 in Bugliosi).

- Photographic evidence. In 2003, computer animator Dale Myers performed a thorough epipolar geometric analysis of available photographic evidence from the crime scene (primarily home movie films taken of the motorcade) and concluded that H.B. McLain’s motorcycle was approximately 175 feet from the location found by the HSCA acoustic experts (BBN and W&A) just half a second before the first shot.

- Analysis of Channel 1 audio, including motorcycle engine speed. In 2013, Sonalysts analyzed the DPD Dictabelt recording (Channel 1) and rigorously determined from a number of different considerations (including the motorcycle engine speed) that the “data uniformly indicate that the motorcycle with the open microphone was not part of the motorcade” (Olsen and Martin, 2013).

Each of these arguments, taken individually, independently discredits or seriously calls into question the DPD recordings as “acoustics evidence” of multiple gunmen in Dealey Plaza (implying a JFK conspiracy, as concluded by the HSCA). However, with the exception of the first line of arguments based on timing inconsistencies (mostly involving crosstalk between Channels 1 and 2), the remaining facts argued above about the DPD recordings were mostly glossed over or ignored entirely by Thompson.

But my own initial objection to the DPD recordings as acoustics evidence was more elementary. As I continued my foray into this topic, there was something on the surface that bothered me.

I found myself immediately doubting this claim that there was a 95% confidence of a Grassy Knoll shot (Don Thomas actually elevates this “confidence” to a ridiculous number in his book), when one cannot even hear the sound of gunshots on the recording. Of course, as a scientist I’m well aware that our immediate five senses are not the last word on what we can know about reality. For that matter, one also cannot readily “see” the forward head snap on JFK’s head when watching the Zapruder Film at full speed. But, nevertheless, our senses are still “instruments” well-adapted to ascertaining information about the physical world, and it is from these that we gain intuition allowing us to formulate scientific hypotheses.

We are told that we can’t distinguish the gunshots on the recordings with our ears, but why is that? One reason, of course, is the AGC feature designed for damping loud sounds coupled with a loud background sound (motorcycle engines), which kicks the base level gain down. But what exactly does this mean? In this case it means, among other things, a key piece of audio information is missing from the DPD recordings, namely the amplitude information (i.e., sound volume) in the waveforms. The DPD recordings simply do not contain sufficient information to distinguish gunshots from other potential sources.

So, what did the HSCA investigators (Barger and W&A) claim to find? In a nutshell, they looked for and found waveform patterns from Dealey Plaza test configurations involving gunshots from two locations (the TSBD and the Grassy Knoll) that matched those on the Channel 1 recording. The problem is the waveforms on the Channel 1 recording have been significantly truncated in amplitude-space due to the AGC. Especially without this additional information about the nature of the sounds (i.e., amplitudes well beyond the AGC truncation level), there might very well be other sources that could lead to the suspect waveform patterns (including the impulses attributed to echoes).

And I subsequently found that I was in good company in this line of reasoning. Both Michael O’Dell and Sonalysts (Olsen, Bamforth, and Grant, 2013) were way ahead of me, having already made arguments to this effect, and they have demonstrated it using their own independent analyses.

Sonalysts simply analyzed the waveforms and found that the impulse patterns attributed to gunfire were not uncommon on the Channel 1 recording and could have resulted from any number of sources, including mechanical noises from the open-mic motorcycle.

O’Dell has gone further by clarifying precisely what was meant by W&A’s “95% confidence” (or the exaggerated 99.999% confidence boasted by Don Thomas), and it is not anywhere close to saying that “we are 95% confident there was a Grassy Knoll shooter.” We are not even in the same ballpark.

As Mark Twain is reputed to have said, “Facts are stubborn things... but statistics are more pliable.”

Statistical significance tests are extremely useful tools for determining if relationships in sample data are meaningful and not the result of blind chance, but the relationship in question must be explicitly and precisely defined, and the conclusions deduced in accordance with the specific relationship under consideration. In this case what was meant by “confidence” was simply that the matches between the impulse timing patterns on the Dictabelt with the test impulses were extremely unlikely (e.g., 95%) to have been the result of randomness.

That’s all well and good, but the original recording signals were not random—there were in fact many real, non-random signals, including motorcycle (engine and other mechanical) sounds, heterodynes, and of course, voice broadcasts and crosstalk by DPD officers. And even if we assume for sake of argument that the Channel 1 background signals were completely random, we have only determined that the waveform pattern matches were due to a non-random signal that still could have had any number of sources. So, we find that there was an implicit assumption that the recorded signals were either impulses associated with gunshots (including echoes), or random noise.

And here is the clincher: Based on his own waveform analysis of the Decker HOLD broadcast, O’Dell has plausibly argued (and convinced me) that the suspect “gunshot” waveforms were, in fact, due to the HOLD crosstalk itself.

That is to say, the “acoustics evidence” may in fact be nothing more than the non-random waveform signal caused by the vocalization of the words “hold everything secure until...” on the Channel 1 recording. For more details on this, the reader is referred to O’Dell’s excellent online article (hosted on the McAdams Kennedy Assassination website): The acoustic evidence in the Kennedy assassination. Specifically, Figure 4 (op. cit.) shows the exact overlap between Decker’s voice and the suspect “Grassy Knoll” shot.

But regardless of the suspect waveform source (whether it was the HOLD crosstalk or some other non-random source signal), there is now therefore a third (in my opinion, more fundamental) argument that should be added to the above list: In addition to the timing issues and open mic assumptions, the DPD recordings do not contain sufficient information for the suspect impulses to be uniquely identified as gunshots. In layman’s terms, the Channel 1 waveforms are not the equivalent of “ballistic fingerprints.”

Even if we assume for sake of argument that the motorcycle with the Channel 1 open mic was in the motorcade, and located at the requisite place and time near the intersection of Houston and Elm (in spite of photographic and audio evidence to the contrary), the suspect impulses could still have originated from any number of sources, including the spoken words “Hold everything secure” that occurs simultaneously on the Channel 1 recording (regardless of whether or not one wants to deny that those words were crosstalk).

This means that the best one could ever hope to claim from the DPD recordings was that the waveforms could possibly have been caused by a gunshot from the Grassy Knoll, but this was not to the exclusion of other possible causes—possibilities that both O’Dell and Sonalysts have subsequently identified as, for example, the spoken words “Hold everything secure,” or a microphone rattling on the motorcycle (among other possibilities).

But the “other possibilities” go even further than waveform audio sources.

O’Dell has also performed his own acoustical model simulation of Dealey Plaza (akin to W&A, albeit using a computer), and he actually found numerous waveform “matches” with gunshots fired from other various locations in Dealey Plaza, some of them laughable; for example, a gunshot originating at Zapruder’s pedestal produced multiple matches with open mic motorcycle locations in Dealey Plaza. Therefore, from the DPD recordings alone, one also cannot rule out gunshots from other locations.

That, to put it mildly, is a far, far cry from the claim that there’s a 95% confidence of a gunman on the Grassy Knoll.

To recap, there are three general categories of arguments that continue to discredit the “acoustics evidence,” each with their own independent lines of reasoning, “resurrection” notwithstanding:

- Timing issues.

- Open mic location assumptions.

- Insufficient information-content within the DPD recordings.

Thompson all but ignores the second and third set of arguments. Although the third (in my opinion) is the most fundamental of the three, it is also the least known or argued, so we can certainly cut Thompson some slack on that. But we are not yet done discussing the first one, because Thompson attempts (with a certain dramatic flair) to mount a renewed defense of CHECK.

Thompson’s Defense of the “Acoustics Evidence” and Barger Redux

In spite of what we have since learned about the DPD recordings in the decades since the HSCA’s rash decision to insert its analysis into the JFK case, Thompson has remained committed to the spectre of a Grassy Knoll gunman. Thompson makes a final attempt to gain the upper hand on the ghost of Luis Alvarez, who has apparently lived on within the “Ramsey Panel survivors.” He devotes his concluding chapters in Part IV to a defense of the acoustics evidence against the rebuttal of the CHECK crosstalk by those survivors (Linsker et al.).

In support of the alleged CHECK crosstalk event, Thompson first offers two simple arguments that he arrived at with his Editor, John Grissim, who had become a “true collaborator” with him on his crusade against the Ramsey Panel survivors. They also came up with simple, easily remembered names for their arguments, namely “the unshrinkable 88 seconds,” and “move one, move all.” These are followed by what was apparently meant to be a coup de grace, namely an encore from one of the original acoustical experts for the HSCA, James Barger. We will now examine each of these.

The “Unshrinkable 88 Seconds”

Thompson is here referring to an irreconcilable time difference between the original CHECK and HOLD transmissions on O’Dell’s time-corrected Channel 2 recording versus the time difference between their suspect Channel 1 crosstalks. The time difference on Channel 2 is 98.7 s, but the difference on Channel 1 is only 10.9 s, thereby leaving a minimum 87.8 s of time unaccounted for between the two events on Channel 1. It’s called “unshrinkable” because if the Channel 2 recording has intermittent missing times (due to periods of radio silence when the Audograph automatically shut-off to conserve the recording medium) that would increase, not shrink, the discrepancy. Thus far, this is all true. Thompson concludes that this “unshrinkable” time on Channel 2 means that the HOLD crosstalk on Channel 1 is an “artifact” (i.e., it got there by some other means).

However, this conclusion is not only wrong, but the proper conclusion is actually the opposite of what Thompson claims. This time discrepancy merely indicates that these two Channel 2 transmissions (CHECK and HOLD) could not both be Channel 1 crosstalks, but from this information alone, we do not know which.

To answer that question, O’Dell points out that one needs to check for consistency with the other established time markers. This involves examining the time differences of these two with nearby established simulcasts (broadcasts on both channels) and crosstalks (viz., the “HOLD family”: “BELLAH1,” “BELLAH2,” and “I’VE GOT”), and looking to see elapsed times between the event pairs on the Channel 1 continuous recording are greater or equal to those on Channel 2 (i.e., Δtch1 ≥ Δtch2). O’Dell has performed this test and he has confirmed that the elapsed times between HOLD and other events on Channel 1 are indeed all greater than those on Channel 2 (i.e., for HOLD, Δtch1 > Δtch2 as required).

But what about CHECK? Perhaps not too surprisingly, for CHECK the opposite is true: Elapsed times between “CHECK” and the other reference events (BELLAH1, BELLAH2, I’VE GOT, SIMUL) on the Channel 1 recording were smaller than those on Channel 2, which is an impossibility. Thus, while the “unshrinkable 88 seconds” does indicate that something was amiss between the timings of the alleged “CHECK” and HOLD events on Channels 1 and 2, when similar comparisons are performed for other event pairs, we find that HOLD is universally consistent and CHECK is universally inconsistent. Therefore, we have just stumbled upon another independent argument that points to the fact that the alleged “CHECK” event on Channel 1 is not a Channel 2 crosstalk.

“Move One, Move All”

Thompson’s second argument is related to “the unshrinkable 88 seconds” in that it tries to address the missing time on Channel 2 due to the recording dropouts from the automatic shutoff feature. The Ramsey Panel deduced from various time-marker events that the amount of missing time was 46 seconds. Thompson questions how likely it would be that they would somehow come up with exactly what they “needed” (46 seconds), as if they were somehow back-engineering it, but they did not “need” anything. Forty-six seconds was simply the deduced missing time—there was nothing special or required about the value.

But Thompson further argues that this insertion of missing time would not only “move” all the earlier Channel 2 events back in time, but it would also move the events back in space, thereby moving Chief Curry in the lead car back onto Main Street when he was announcing that he was at the Triple Underpass in Dealey Plaza. Admittedly, this one had me initially scratching my head, because on the surface it seemed a reasonable proposition. But Michael O’Dell was not so easily convinced, and he explained to me how the argument was fatally flawed.

First, it should be noted that because the Channel 2 recording has pauses, the discovery and determination of missing time between location broadcasts (by Curry) should come as no surprise to anyone. Consequently, the insertion of time determined to be missing (approximately on the order of a minute or less) between locations on Channel 2 due to recorder pauses does not necessarily interfere with the car location (during the continuous Channel 1 broadcast) provided that (1) the rule Δtch1 ≥ Δtch2 is not violated, and (2) we do not violate any physical limits regarding the motorcade movement (i.e., the limo speed) on Channel 2.

In other words, there is no issue with inserting time on Channel 2 so long as the recorded time between events on Channel 2 is less than or equal to the recorded time between the same events on Channel 1, and that the time insertion does not involve impossible limo speeds.

But let’s assume for sake of argument that the Channel 2 recording did run continuously. Time insertion on Channel 2 still does not move events because the timeframe in question occurred following the last location call-out by Curry at the Triple Underpass—in other words, we are not inserting time between known events in the assassination sequence. This means that the Channel 2 events are not altered in the least because there is nothing “anchoring” them to any time or location—they are all free to slide together in unison and retain their relative positions within the recording timeline, without even altering the limo speed.

Barger Redux